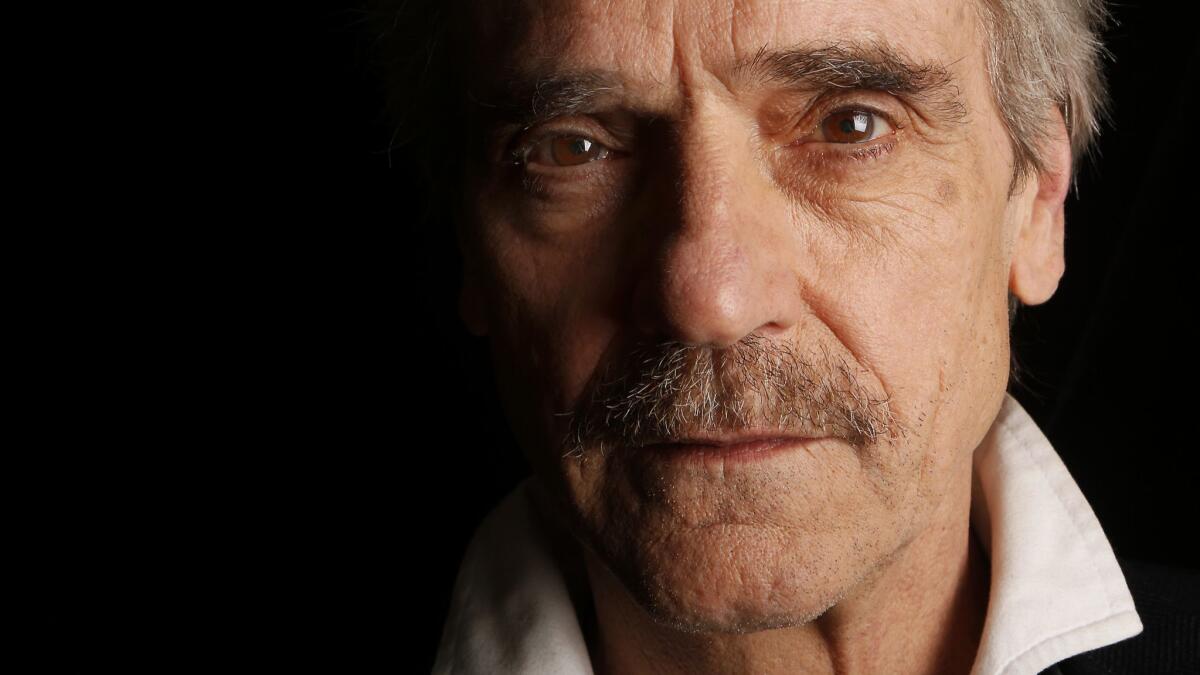

Jeremy Irons would be ‘very happy’ if ‘Long Day’s Journey,’ coming to the Wallis, was his swan song

Reporting from London — Jeremy Irons arrives at the Beaumont Hotel on a motorcycle, a method of transportation that becomes an issue when it begins to blizzard midway through an interview about the actor’s role in “Long Day’s Journey Into Night.”

He’s speaking in March, prior to one of the West End performances, where director Richard Eyre’s production of Eugene O’Neill’s semi-autobiographical work has resurfaced after playing two years ago at the Bristol Old Vic. Irons joined the cast after working with Eyre in “The Hollow Crown” and was drawn in by the potential challenge of playing family patriarch James Tyrone opposite Lesley Manville’s Mary Tyrone.

“In your 30s and your 40s, that’s when you keep getting challenges chucked at you,” the 69-year-old Irons says, sitting in the hotel’s members’ bar. He speaks slowly and cautiously, sometimes trailing off before completing a thought. “And then people begin to start asking you to do what you can do. When you get the opportunity for a challenge it’s really good, you know, because you can’t rest on your laurels doing films and earning a lot of money all the time.

“Doing a part like this — it requires a tremendous amount of energy. Each night you’re trying to throw a bowling ball down the middle and knock all the skittles over. It’s very satisfying when you think you have been part of creating something for an audience.”

The play, which ran for several weeks at BAM in New York after leaving London, is set to open this week at the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts in Beverly Hills. It represents the sort of role Irons is seeking. Asked whether he had any concern over the part, Irons displays his low-key British sense of humor.

“I thought, ‘Why not?’” he says. “In a few years I won’t be able to remember the lines at all and won’t have the energy for it. So let’s do it — whether it be a swan song, I don’t know. If it were to be I’d be very happy.”

To play James Tyrone, Irons went deep into research, something he’s never really done before for a play. He looked at videos of other actors playing the role such as Jack Lemmon and Christopher Plummer, and read O’Neill’s autobiography. He remembers seeing Laurence Olivier play James Tyrone several decades ago on the West End, a performance that stuck with him.

“I saw what choices people had made and whether I agreed with them or not,” the actor says. “It’s just interesting to look and see whether there’s anything they’ve come up with. But, in fact, I never found there was. I think it’s all part of claiming something, which you have to do when you play one of these parts. You have to claim it yourself.”

This particular version of O’Neill’s work features a notably contemporary-looking set. Although there are obvious moments that denote its 1912 setting, the play resonates as a modern piece. The inherently simple story, following the Tyrone family from breakfast into the late evening as repressed pain comes to the surface, tackles issues of drug addiction, parental disappointment and disillusionment with one’s life choices.

“Yes, we’ve got period costumes on and it’s set in 1912, but you could do an updated version of this and not change it at all,” Manville says, calling from New York where the show is still playing. “It’s about addiction and family problems and drink and alcoholism and loneliness. Everything about it is completely contemporary, which is why the play leaves people so shattered. They can see echoes of their own lives.”

Irons is struck by the complexity of his character and the difficulties of presenting that onstage.

“You have to not [care] whether the audience likes you,” Irons says. “This is a man who has lived with an addict for however many — 27 — years. How do you deal with that? To an outsider it might seem really heartless. That’s the reality of it. Towards the end you realize that the man is not exactly proud of his life. He’s disappointed with his children, which a lot of men are, and he’s at his wit’s end about his wife.

“But we soldier on. And I think soldiering on is one of the most endearing qualities in life. We all have difficult times and we just deal with it and I love that quality. That’s something of what this play does for an audience.”

“Long Day’s Journey Into Night,” first performed in 1956, can sometimes top out at more than four hours, however with this production Eyre and the actors made a conscious choice to amp up the pacing. The opening scene, as the Tyrone family finishes breakfast, is jarringly quick, with Mary, James and their two sons speaking rapidly over each other.

“I’m aware of how we all talk over each other, especially families,” Irons notes. “Little cracks begin to show and it gives us somewhere to go from. It gives it a life and a racket.”

Eyre also intentionally never blocked the play during the rehearsal periods, either for its initial run in Bristol or its current run. The movement onstage feels organic, as if the characters are really in the space, and Irons enjoys the freedom to feel out the moments as they unfold in the story. “We just did what was natural,” the actor says. “And it’s not set in stone. We change things a bit. It just sort of evolved.”

For Irons, the sense of constant effort and evolution is essential to the acting experience. He’s mostly bored of movies, which he feels are too piecemeal in process, and admits that some of his film choices are mainly financial. He enjoyed making this year’s “Red Sparrow,” but he doesn’t feel like he’s being offered as many juicy parts as he used to, roles like his Oscar-winning performance in 1990’s “Reversal of Fortune.”

Which is why he prefers to tackle really challenging roles onstage.

“When it’s difficult I love it,” Irons says. “It’s like anything – like jumping a really difficult horse in an arena and just getting it right. Or not. And then thinking ‘Well, next time I’m going to get it right.’ Trying to hone it. I love that process. I think that’s what keeps me going.

“Which means that when I have a difficult project, a project that draws a lot out of me, then it’s much more satisfying than something you can just turn up and do. Those are always plays. And in the early days the movies, working really closely with the director. You have the thrust of the film. That can provide much the same satisfaction. I haven’t really played any major roles in film lately. And because filming is so fragmented it’s never really quite as satisfying.”

He adds, “I would be fine not doing anything after this, really. I like being at home more and more.”

The performances at the Wallis mark the end of Eyre’s production, although Irons originally wanted to take it around the world. The characters have seen a real evolution since their inception in Bristol, though Manville isn’t certain the audience will actually be able to perceive that on a given night.

“If you’re doing things right with a play you do carry on discovering,” she notes. “It’s a live event and you’re working with other actors and they might give you something different that provokes something else. It’s, to a degree, set. But there has to be a fluidity with a play otherwise it’s quite boring for you every night.”

There’s nothing on Irons’ slate once the play wraps, which doesn’t bother him. It’s possible that he’ll continue his role of Alfred Pennyworth in the DC films, although nothing is confirmed.

“The great joy is you never know what’s around the corner,” he says. “That’s what I’ve always loved about the business. You never know what’s going to turn up. And for someone who’s very happy if nothing turns up, it’s a perfect life, really.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.