From the Archives: Unmasking Oscar: Academy voters are overwhelmingly white and male

The 2016 Academy Awards nominations were announced Jan. 14, and for the second year in a row all acting nominees were white. The lack of diversity, despite strong minority contenders, has renewed criticism and reenergized the hashtag #OscarsSoWhite, first created after last year’s nominees were announced. Four years ago, The Times investigated the make up of the Academy in depth.

When the names of winners are revealed on Oscar night, months of suspense give way to tears, smiles and speeches. Yet when the curtain falls, one question remains: Who cast the votes?

About 37 million people tuned in to the Academy Awards last year, and a great deal rides on the show’s outcome. Winning a golden statuette can vault an actor to stardom, add millions to a movie’s box office and boost a studio’s prestige. Yet the roster of all 5,765 voting members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences is a closely guarded secret.

Even inside the movie industry, intense speculation surrounds the academy’s composition and how that influences who gets nominated for and wins Oscars. The organization does not publish a membership list.

“I have to tell you,” said academy member Viola Davis, nominated for lead actress this year for “The Help.” “I don’t even know who is a member of the academy.”

A Los Angeles Times study found that academy voters are markedly less diverse than the moviegoing public, and even more monolithic than many in the film industry may suspect. Oscar voters are nearly 94% Caucasian and 77% male, The Times found. Blacks are about 2% of the academy, and Latinos are less than 2%.

Oscar voters have a median age of 62, the study showed. People younger than 50 constitute just 14% of the membership.

The academy calls itself “the world’s preeminent movie-related organization” of “the most accomplished men and women working in cinema,” and its membership includes some of the brightest lights in the film business — Tom Hanks, Sidney Poitier, Meryl Streep and Steven Spielberg, among others. The roster also features actors far better known for their television acting, such as Erik Estrada from “CHiPs,” Jaclyn Smith of “Charlie’s Angels” and “The Love Boat’s” Gavin MacLeod.

The academy is primarily a group of working professionals, and nearly 50% of the academy’s actors have appeared on screen in the last two years. But membership is generally for life, and hundreds of academy voters haven’t worked on a movie in decades.

OSCARS 2016: Full coverage | List of nominees | #OscarsSoWhite controversy

Some are people who have left the movie business entirely but continue to vote on the Oscars — including a nun, a bookstore owner and a retired Peace Corps recruiter. Under academy rules, their votes count the same as ballots cast by the likes of Julia Roberts, George Clooney and Leonardo DiCaprio.

To conduct the study, Times reporters spoke with thousands of academy members and their representatives — and reviewed academy publications, resumes and biographies — to confirm the identities of more than 5,100 voters — more than 89% of the voting members. Those interviews revealed varying opinions about the academy’s race, sex and age breakdown: Some members see it simply as a mirror of hiring patterns in Hollywood, while others say it reflects the group’s mission to recognize achievement rather than promote diversity. Many said the academy should be much more representative.

The Times found that some of the academy’s 15 branches are almost exclusively white and male. Caucasians currently make up 90% or more of every academy branch except actors, whose roster is 88% white. The academy’s executive branch is 98% white, as is its writers branch.

Men compose more than 90% of five branches, including cinematography and visual effects. Of the academy’s 43-member board of governors, six are women; public relations executive Cheryl Boone Isaacs is the sole person of color.

“You would think that in this day and age, there would be a little bit more equality across the board, but that’s not the case,” said Nancy Schreiber, one of a handful of women among the cinematography branch’s 206 voting members. “Being a cinematographer should not be gender-based, and it’s ridiculous that it is.”

Academy leaders including President Tom Sherak and Chief Executive Dawn Hudson said they have been trying to diversify the membership but that change is difficult because the film industry is not very diverse, and slow because the academy has been limiting membership growth for the last decade.

“We absolutely recognize that we need to do a better job,” said writer-director Phil Alden Robinson, a longtime academy governor. But “we start off with one hand tied behind our back.... If the industry as a whole is not doing a great job in opening up its ranks, it’s very hard for us to diversify our membership.”

Independent studies of some film crafts show that the academy’s demographics mirror the industry’s. Women make up 19% of the academy’s screenwriting branch, and a 2011 analysis by the Writers Guild of America, West found that women accounted for 17% of film writers employment. The academy’s producers branch is about 18% female, and the directors branch is 9% female, figures comparable to those in a study by San Diego State University’s Martha Lauzen. She examined the 250 top-grossing movies of 2011 and found that women accounted for 25% of all of the films’ producers, and 5% of all their directors.

“Is most of commercial narrative filmmaking the product of mostly white men? Sadly, the answer is yes,” said Alexander Payne, the director and co-writer of best picture nominee “The Descendants” who belongs to the director branch.

Frank Pierson, a former academy president who won an Oscar for original screenplay for “Dog Day Afternoon” in 1976, said merit is the primary criterion for membership.

“I don’t see any reason why the academy should represent the entire American population. That’s what the People’s Choice Awards are for,” said Pierson, who still serves on the board of governors. “We represent the professional filmmakers, and if that doesn’t reflect the general population, so be it.”

Some academy members, though, believe the organization should do more to reflect the demographics of the nation. Denzel Washington, who won the lead actor award for 2001’s “Training Day,” said the academy needs to “open it up” and “balance” its membership.

“If the country is 12% black, make the academy 12% black,” Washington said. “If the nation is 15% Hispanic, make the academy 15% Hispanic. Why not?”

A frequent criticism

Questions about the academy’s diversity, or lack thereof, have persisted for years. In 1996, the Rev. Jesse Jackson organized nationwide protests over the absence of black and minority Oscar nominees, claiming it was evidence of “race exclusion and cultural violence” in Hollywood. The question came to the fore again last year, when not a single minority was among the 45 people nominated for actor, actress, supporting actor and actress, director and original and adapted screenplay.

In the past 83 years of Oscars, less than 4% of the acting awards have been bestowed on African Americans. Only one woman — Kathryn Bigelow — has received the Academy Award for directing “The Hurt Locker.”

After the 2011 ceremony was staged without a single black male presenter, actor Samuel L. Jackson complained in an email to The Times: “It’s obvious there’s not ONE Black male actor in Hollywood that’s able to read a teleprompter, or that’s ‘hip enuf,’ for the new academy demographic!”

Asked about the diversity of Oscar presenters, Sherak said officials did not instruct this year’s ceremony producers, Brian Grazer and Don Mischer, to include more minorities. “Producers produce the show, end of subject,” he said. Past Oscar hosts have included African Americans Chris Rock and Whoopi Goldberg, and Eddie Murphy was initially slated to host this year’s broadcast.

Age and gender have also prompted questions. Sony Pictures executives said last year that they believed their Facebook film “The Social Network” lost the best picture race to “The King’s Speech” because older Oscar voters didn’t relate to the Internet story. This year, some believe that Stephen Daldry’s 9/11 drama “Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close” made the best picture shortlist because it appealed to middle-aged men.

“The film is about men trying to be good fathers, sons trying to be good sons,” said Terry Press, a member of the public relations branch who for years has helped mount Oscar campaigns for filmmakers. “It’s about unfulfilled conversations with your father and that’s an extremely middle-aged man thing. It’s like ‘Field of Dreams.’”

African American actress and academy member Alfre Woodard, 59, cited the sexually explicit “Shame,” which got no nominations, as an example of a film whose Oscar hopes may have been doomed by the academy’s demographics. “Maybe if the median age was 45 to 50, a film like ‘Shame’ might show up, which I thought was a brilliantly rendered piece but a subject matter that you don’t expect a certain older demographic would flock to see,” she said.

Woodard, who joined the organization in 1985 and has been active on academy committees, said she often encourages women to apply for membership in the academy, believing the best way to effect change is from within. “It’s like sitting out an election,” she said. “The country is only going toward its ideals when people participate.”

But others have lost patience. Academy member Bill Duke, a black actor and director, said: “The black community sees the academy as an entity that ignores the needs, wants, desires and representation of black directors, producers, actors and writers. Whether it is true or not, that is how it’s perceived — as an elitist group with no concern or regard for the minority community and industry. And there doesn’t seem to be any desire to change that perception.”

Some academy critics believe the organization, through its membership and Oscar picks, reinforces a lack of diversity on screen and in studio decision-making.

“People of color are always peripheral,” said veteran African American character actor Bernie Casey (“Under Siege”), who said he recently quit the academy because he was disenchanted with its racial makeup. “Asians, Latinos, black people — you never see them. We are 320 million people in America and about 48 million black people and the same of Latin descent — but you would not believe that based on what you see in films and television shows.”

This year, several minorities did land nominations in the acting categories: Davis and her fellow cast member from “The Help,” supporting actress nominee Octavia Spencer, and Demián Bichir, a Mexican-born performer who starred in “A Better Life.” All of the year’s five nominated directors are white men, and none of the 21 producers of the nine best picture nominees is a person of color.

Were there more Latino academy members, Bichir said, opportunities for Latinos would improve. “That would mean there would be a lot more roles for Latin actors,” the actor said, “and a lot more movies for [Latin] cinematographers.”

Growth and change

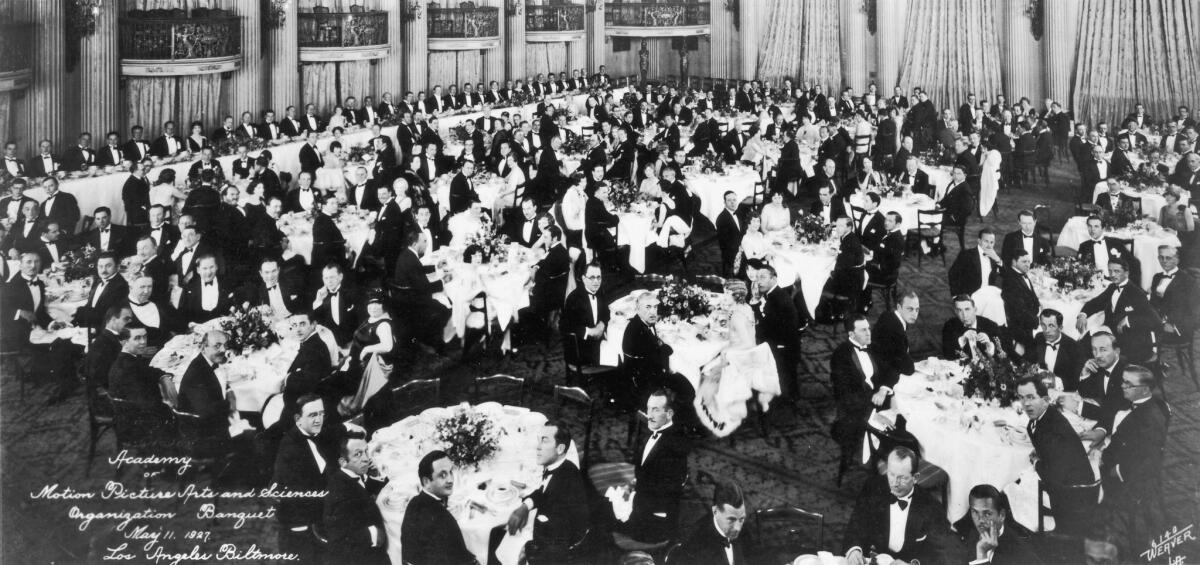

The academy was founded in 1927 with two aims: to mediate labor disputes and improve the movie industry’s image. Louis B. Mayer, the legendary head of MGM, initiated the idea and invited an elite cadre of professionals, including actress and United Artists studio co-founder Mary Pickford, director Cecil B. DeMille and producer Irving Thalberg, to join.

The academy’s membership grew steadily over the years as the organization moved away from labor management issues to focus on film preservation, research and the Oscars, first presented in 1929 in the Blossom Room of the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel.

Today, the academy oversees more than $196 million in assets and dispenses more than $20 million in grants and scholarships a year, including to Streetlights, a job training and placement group that works to promote ethnic diversity in Hollywood. It donates $750,000 annually to film festivals around the country and sponsors an annual screenwriting competition that rewards winners with $35,000 fellowships. According to its tax filing for the 2009-2010 fiscal year, the Oscars generated $81.3 million in total revenue for the organization.

The academy grew rapidly between 1990 and 2000, adding close to 800 members. Former executive director Bruce Davis alerted the board to the steep increase and noted there had not been a commensurate growth in the film business. The organization attributed the membership surge to a relaxed attitude toward admission.

“The guilds are a democracy. If you have credits, nobody asks how good you were,” said Davis, the executive director from 1989 to 2011. “But the academy has to be different.”

In response, the organization in 2004 began limiting membership growth to 30 per year, not including those admitted to fill vacancies created by deaths, resignations or retirement. It also clarified and stiffened its policies for admittance. The available slots are allocated among the 15 branches and the academy’s at-large division.

There are three ways to become a candidate for membership: land an Oscar nomination; apply and receive a recommendation from two members of a branch; or earn an endorsement from the branch’s membership committee or the academy staff.

The membership committees then vote on the candidates; those who get a majority are invited to join. The academy says almost everyone accepts the offer.

Actors, for example, now must have three significant credits to be considered for membership, and producers need two solo producing credits or the equivalent. Such criteria benefit people with more experience. “The academy is always going to be slightly older — if just because you have to have about five years of credits before you’re even considered,” said Joe Letteri, a four-time Oscar winner for visual effects.

In practice, the bar for admittance varies widely from branch to branch. Last year, actress Rooney Mara and visual effects supervisor Tim Burke were among 178 invitees academy wide. Mara had had small roles in “The Social Network” and “A Nightmare on Elm Street” (she had yet to star in her current Oscar-nominated role in “The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo”). Burke, in contrast, had won an Academy Award a decade earlier for his work on “Gladiator.”

The academy began making public the names of its invitees in 2004, but does not say which ones accept and become members.

The more than 1,000 people invited to join since 2004 include black actors such as Jennifer Hudson, Mo’Nique and Jeffrey Wright. But overall, the group was only slightly more diverse than the academy it was joining — 89% white and 73% male. Sherak pointed out that in 2011, the invitees were 30% female and 10% nonwhite.

The academy’s overall composition before and after the 2004 policy shift remained close to 93% Caucasian and 76% male, and its median age dropped from 64 to 62.

As part of the 2003 tightening of membership rules, Davis urged that a wider circle of potential invitees be considered. In 2009, he suggested to the sound branch committee that it had overlooked India’s Resul Pookutty, who won an Oscar that year for sound mixing on “Slumdog Millionaire.” Davis admired the technician’s work and was moved by his emotional acceptance speech on Oscar night. (The committee extended the invitation a year later.)

“When I got the letter from them saying they would like to invite me into the academy, I was literally screaming in the studio,” said Pookutty, who flew from Mumbai to Los Angeles to attend the new member luncheon. “It means a great deal. More than the pride of it, I feel that my whole fraternity in India has been recognized and honored.”

Sherak and other academy officials said they’re eager for more applications from women and minorities, and more involvement from those who are already members.

“I’m hoping your story runs and 7,000 phone calls break the lines here,” Sherak said. “We’ve been trying to reach out to the constituency and we’re looking for help. You want to be on a committee? Tell us what committee. If you are sitting waiting for us to find your name in our make-believe book and we are going to call you, we are not going to do that. Come to us, we’ll get you in. We want you in. That would help us a lot.”

Times staff writers Jasmine Elist, Deborah Vankin, Reed Johnson and Emily Rome contributed to this report.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.