Just in time for opening day, a new book on the (complicated) history of Dodger Stadium

Distrust of elites and their backroom deals. A severe housing shortage in Los Angeles. Ballot measures testing Angelenos’ appetite for change and large-scale development. Controversies over public subsidies that help the wealthy owners of professional sports teams move from one city to another.

Sound familiar? Quite a few of the themes at the heart of a thoughtful new book from Princeton University Press on the history of Dodger Stadium, which celebrates another opening day Monday afternoon, have also been generating a steady supply of headlines in 2017. They’re central to ongoing arguments about density and the construction of new housing in Los Angeles, the role of patrons like Eli Broad and the relocation of the NFL’s Rams and Chargers to Inglewood and the Raiders to Las Vegas.

“City of Dreams: Dodger Stadium and the Birth of Modern Los Angeles,” by Jerald Podair, a professor of history at Lawrence University in Appleton, Wis., in that sense makes an implicit argument that the fissures opened up by the fight to get the stadium built have yet to close.

That fight was a tougher and more complex one than even many longtime Dodger fans likely know. The decision to give city-owned land in Chavez Ravine to Walter O’Malley as he considered moving the Dodgers from Brooklyn to Los Angeles in 1957, in exchange for his willingness to finance a new stadium there, is one that has been much analyzed since. Infamously, that land had been aggressively cleared of its longtime residents, most Mexican Americans, to make room for a public housing project that was killed by red-baiting attacks.

Podair makes clear that the struggle over that housing project, designed by the leading modernist architects Richard Neutra and Robert Alexander, was virtually over by the time O’Malley accepted the city’s offer to use the land. He notes that the “city of Los Angeles, not the Los Angeles Dodgers, destroyed Chavez Ravine.”

He lets O’Malley off the hook a bit for not looking more deeply into the process that had allowed the land in Chavez Ravine to be handed to him by the city as essentially a tabula rasa, with only a handful of residents remaining from what had been a tightknit neighborhood.

“When he arrived in Los Angeles,” Podair writes, “O’Malley was only vaguely aware of the controversy over public housing in Chavez Ravine and of the impending eviction battle there.”

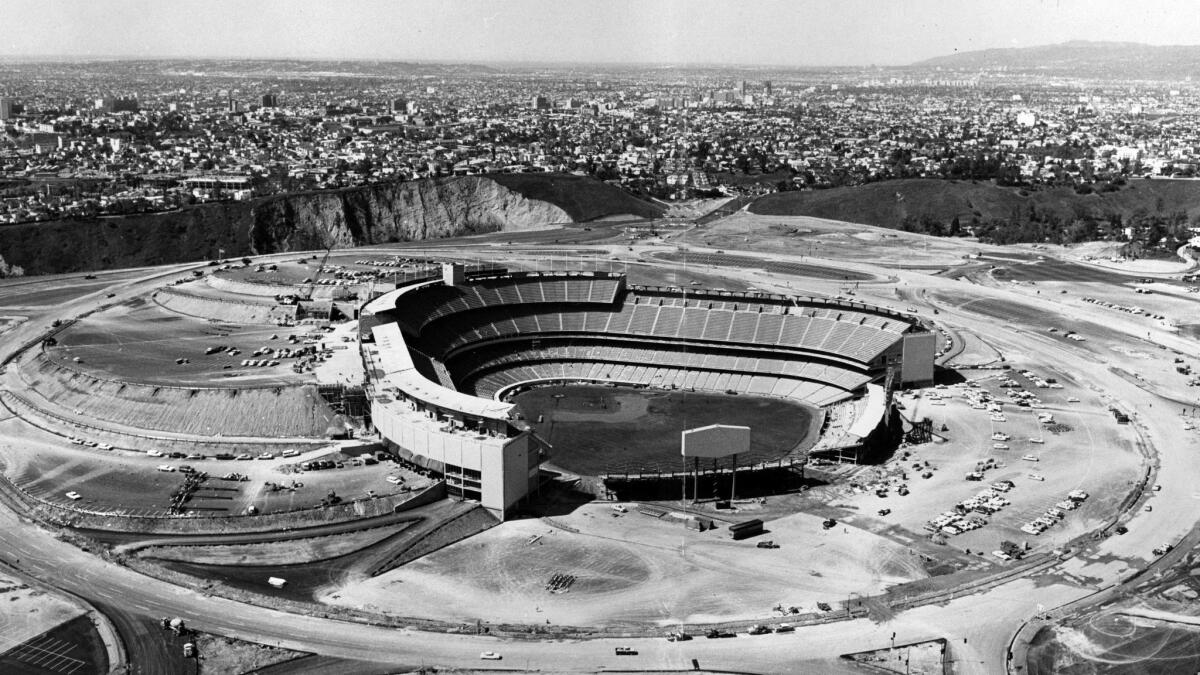

Less known is the extent to which O’Malley had to struggle, once he’d decided to move West, to get his planned stadium approved and built. Even as O’Malley was sketching out plans for a modern ballpark in Chavez Ravine with Emil Praeger, the architect and engineer who had already built the team’s spring-training complex in Vero Beach, Fla., the owner was mounting a legal, political and public-relations effort to win a permanent home for the franchise. Meanwhile the team was playing on a temporary basis at the Coliseum.

The twists and turns of that debate make up the heart of Podair’s book. He writes that the competing arguments about the deal the city had made with O’Malley, with councilmembers like Edward Roybal and John Holland opposing it and Mayor Norris Poulson and the downtown establishment in firm support, stood in for competing arguments about the character of Los Angeles and its future.

“Dodger Stadium divided Los Angeles in deep and profound ways,” Podair writes. “The questions it raised about the relationship between public and private power, the respective roles of urban core and periphery, and the modern identity of Los Angeles itself would remain long after” it opened on April 10, 1962.

The debate, he adds, “pitted the small-property-owning middle class, the working class, and the poor of Los Angeles’ margins — geographic margins, economic margins, racial margins, sometimes all three — against a civic class located closer to the loci of political, economic, and cultural power. One group’s dreams were localist and limited, the other’s national and global.”

After a bruising victory for O’Malley at the City Council, the deal went to the voters in June 1958 in the form of a ballot measure called Proposition B. It won a narrow victory for the Dodger owner, earning 52% of the vote (including surprisingly strong support from Latino voters). Next was a trip through the courts, where O’Malley finally won a conclusive verdict at the California Supreme Court in early 1959. When the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the decision in the fall of that year, O’Malley was finally able to move forward with Praeger in earnest.

That hard-fought victory stands for Podair as an endorsement of the idea that the private gain of an owner like O’Malley might be compatible with the public good, that there could be a distinction, as he puts it, between mere “profit-making” and the more objectionable “profiteering.”

It also marks, he argues, the moment when Los Angeles decided it did in fact need and want to invest in a downtown in a traditional sense. If the “battle against the construction of Dodger Stadium symbolized the revolt of the margins … against perceived centers of power and, indeed, the idea of a center itself,” as he writes, then the center had won. The completion and the success of the stadium, he argues, changed the relationship between center and periphery in L.A. for good and “set the arc of its civic trajectory.” The redevelopment of Bunker Hill and the construction of the Music Center, along with the later additions of Walt Disney Concert Hall and Staples Center: all of this follows in Podair’s telling from O’Malley’s achievement in Chavez Ravine.

I certainly don’t disagree with him about the appeal of the stadium itself, which Times sports columnist Jim Murray memorably called “a gorgeous triumph of high-rise architecture in living Technicolor with levels of ocher, aqua, coral and sky-blue, with umbrellas of concrete escarping a perimeter that looks on the mountains of San Gabriel.” Podair notes, rightly, that Dodger Stadium was “a ballpark built not just to house a team but also to embody an atmosphere.”

But when he calls it “the first baseball stadium in a modernist form” he is not only overlooking San Francisco’s Candlestick Park, which opened in 1960, but also misreading the great architectural appeal of Dodger Stadium, which lies in the way it combines modernist features with more flexible, democratic and site-specific ones.

Dodger Stadium has all the forward-looking optimism of the best modernist architecture and none of its dogmatic insistence on universal solutions, its tendency to ignore or run roughshod over local conditions. Its “atmosphere” is entirely the product of design details in combination with the flexible and generous way it opens itself up to its tricky, hilly site and those views.

It helped of course that unlike Candlestick — and, again, in defiance of modernist architecture’s tendency to believe it could and should be all things to all people — Dodger Stadium was designed only for baseball, allowing Los Angeles to sidestep the disastrous trend in the 1960s and 1970s of building multipurpose concrete bowls shared by NFL and major-league franchises.

The larger question, when it comes to testing Podair’s thesis about the relationship of Dodger Stadium to L.A.’s understanding of itself and the role downtown would play in its postwar development, is how much the ballpark is really of as opposed to merely near downtown. Podair stashes in a footnote the fact that Dodger Stadium, built for a car-centric era and surrounded by oceans of parking, has never been connected in any meaningful way to the city’s transit system.

That is not the only sense in which it has stood apart from the life of the city. Sunk into a hillside, all but invisible from downtown itself, Dodger Stadium was built as an enclave, an oasis whose charm derives in no small measure from its detachment from the city around it. It is not quite emblematic, in political, cultural or architectural terms, of L.A.’s “urban core.”

Podair is right when he observes that Dodger Stadium has always been “one of the rare patches of common ground for a city stratified along lines of class and race,” thanks in part to the stadium itself but also to the franchise’s unusually egalitarian history, including but not limited to Jackie Robinson.

But the truth is that we reach that common ground by removing ourselves from the rest of the city; it is that sense of separation, of viewing both the hills and (in the other direction) the downtown skyline from a remove, that gives Dodger Stadium much of its appeal. Its curious and particularly Southern Californian mixture of urban and suburban amenities — a stadium with a giant parking lot and lush, even Arcadian landscaping in the geographical center of the second biggest city in the United States — has always allowed it to stand out.

The paradox of Dodger Stadium is the paradox of Los Angeles. It’s a ballpark where we find a much-needed civic communion in the middle of the city by leaving the city behind.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

Twitter: @HawthorneLAT

ALSO

Doug Aitken’s ‘Mirage’: a funhouse mirror for the age of social media

A visit to Herzog & de Meuron’s controversial Hamburg concert hall

Frank Gehry’s new jewel-box concert hall in the heart of Berlin

For architects, Trump’s wall reveals as much as it promises to close off

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.