Matthew Shepard’s murder, 10 years later

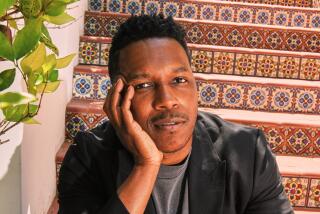

Last fall, as every fall for 10 years, playwright and director Moisés Kaufman was thinking about the 1998 killing of gay college student Matthew Shepard in Laramie, Wyo. Kaufman’s Tectonic Theater Project had gone to Laramie just weeks after Shepard’s horrific murder, interviewed townspeople and transformed their interview tapes into the well-received “The Laramie Project,” produced first as a play and later an HBO film.

But fall 2008 had special meaning. “The 10-year anniversary was coming up, and I started thinking about the long-term impact of Matthew’s murder,” says Kaufman. “I thought if we returned to Laramie, we could have a sense of how an event like that translated into change that is concrete and lasting 10 years later.”

So Kaufman and colleagues from the New York-based Tectonic went back to Laramie, did more interviews, and started writing again. On Monday evening, 150 theaters from New York to Los Angeles, Orlando to Syracuse and Madrid to Hong Kong will host staged readings of the 80-minute “The Laramie Project: 10 Years Later.” Many theater companies and universities have added seminars, panels, film screenings and other programming. It’s an unusually broad-based effort, and one that has implications for American theater at large.

At the heart of both the original play and its epilogue is the killing of 21-year-old Shepard, found barely alive, tied to a fence just outside Laramie. Beaten, robbed and left to die by two local roofers around his age, Shepard was discovered by a bike rider and taken to a hospital. His last days in the hospital received enormous media attention, and Tectonic’s productions further amplified a national dialogue on gay issues and hate crimes.

“There are many in Laramie who think it one of the most important things in their history and many who are ashamed and have tried to rewrite history,” says Kaufman, who also wrote and directed the much-produced “Gross Indecency: The Three Trials of Oscar Wilde.” “We went there with a hypothesis that there would have been great change, and that was correct. Whether the change is for better or worse or both is what people will see when they come to the show.”

The new production also revisits an ambitious experiment of the WPA’s Federal Theatre Project in the 1930s. The Federal Theatre Project created both jobs and low-cost theater, and on Oct. 27, 1936, initiated simultaneous productions of “It Can’t Happen Here,” based on Sinclair Lewis’ novel, in 22 cities.

“We asked: What if we did that with 100 theaters?” says Tectonic’s executive director, Greg Reiner. “People told me we’d never get 100, and we’re now at 150, including all 50 states and eight foreign countries. We believed in the power and importance of this work, and sure enough, other people were as inspired as we were.”

The initial “TheLaramie Project” has already had more than 2,000 amateur and professional productions. “A couple times a month there is a high school production banned or protested or somebody is fired for doing it,” says Reiner. “It is still considered controversial, which is another reason we saw the need to tell the story again.”

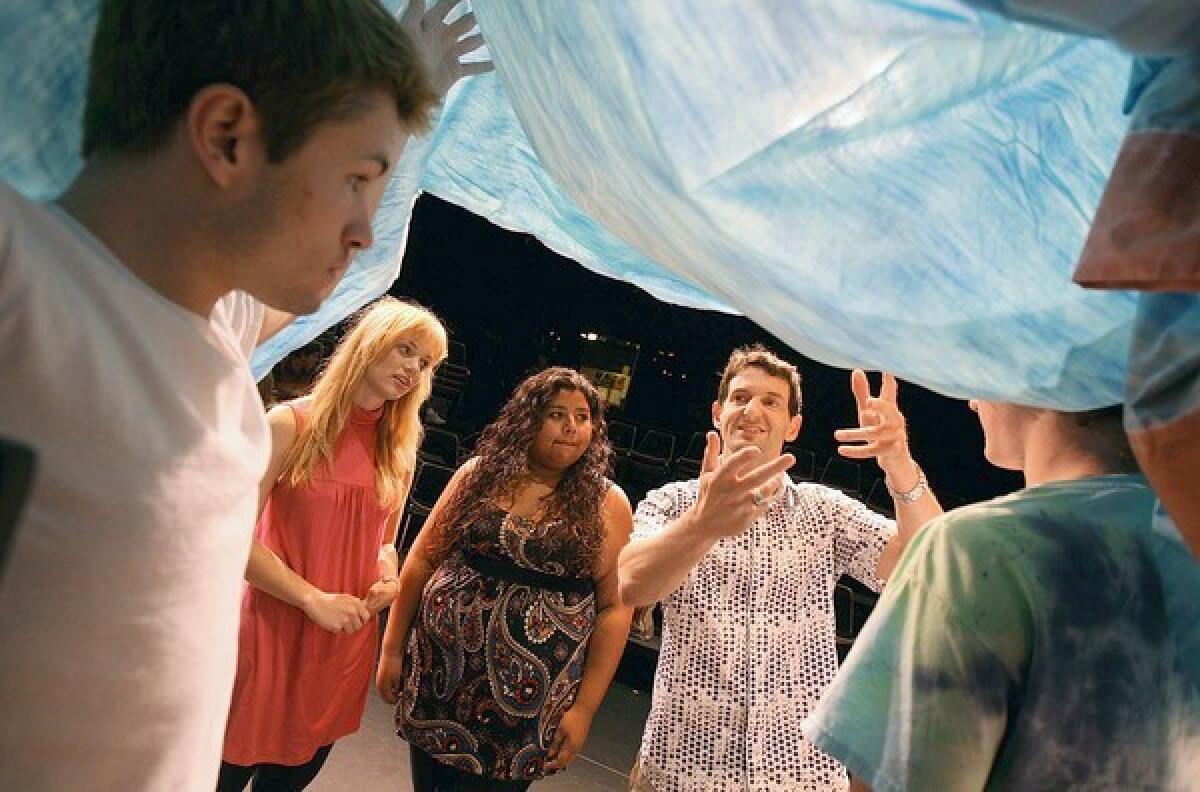

Like the original play, the epilogue captures dozens of Laramie voices. Greg Pierotti, one of the drama’s actor-writers, says this time they interviewed about 85 people, including townspeople interviewed for the first production as well as new people.

They also interviewed Judy Shepard, Matthew’s mother, and Aaron McKinney, one of the two men convicted in Shepard’s murder. “When we did this the first time, it was a play about the town of Laramie and how it reacted,” Kaufman says. “But I feel Matthew’s killers and parents have become part of the narrative. This time we set out to write about how a community has changed.”

Kaufman interviewed Judy Shepard, who has now given hundreds of speeches, written a book and lobbied for hate-crimes legislation. Pierotti spent more than 10 hours over three visits with McKinney, showing up at his prison essentially uninvited. Asked how he felt during the interview, Pierotti says: “My job as an artist is to connect. He did horrible things and said horrible things during our interview, so it’s complicated. You would hope speaking to somebody so directly involved would clarify some of the confusion about motivation and, unfortunately, he is not able to do that. But as one of our characters says, ‘Just because Aaron McKinney is confused about his own motivations, it doesn’t mean it wasn’t a hate crime.’ ”

Pierotti and other Tectonic actor-writers have long been actively involved in helping schools and other organizations produce the Laramie plays, and they’ve been doing so again now. “I’m always incredibly moved by how much people put their hearts into this work,” says Pierotti. “It’s really a testament to the impact of Matthew’s story.”

Through the Laramie Project Online Community, theaters, universities and others have been sharing photos, blogs, forums, videos, updates and problem-solving. A video of excerpts from the actual Laramie interviews is on YouTube, and the writers have been available via conference calls.

On Monday, many productions are being offered free to audiences, while other fee-charging theaters plan to turn proceeds over to community action groups. Participating theaters also will have online connections to Alice Tully Hall at New York’s Lincoln Center, where Tectonic will host a post-performance “talk-back” via a special satellite hookup.

Tectonic company members will perform the work that night at Lincoln Center. Other performers around the country include not just professional actors such as Mary McCormack, Margaret Cho, Barbara Bain and Robert Foxworth, but also students and community leaders.

While the written text will be the same at all 150 venues, productions will vary. At Santa Monica College’s Broad Stage, for instance, 60 members of the Gay Men’s Chorus of Los Angeles and recording artist Randi Driscoll will join the actors onstage. The production’s co-director, Speak Theater Arts’ co-founder Liesel Reinhart, says she had to make musical choices in June before there was even a finished script. Among her choices: music made popular by the Dixie Chicks, Rufus Wainwright, Bob Dylan, Rodgers and Hammerstein and Sons of the Pioneers.

The epilogue also will be produced in a 1,900-seat auditorium at the University of Wyoming in Laramie. “I’m proud of our community and how we have been open to the self-examination that ‘The Laramie Project’ and epilogue have afforded us,” says Leigh Selting, chair of the university’s theater and dance department. “The easy road would have been to say leave us alone, and we’ve not done that. This is an event that left its mark, and the conversations that we’ll have are good to have again.”

At the La Jolla Playhouse, which was among the first regional theaters to present the original play, director Darko Tresnjak adds that the new play’s national reading is good for the theater community as well.

“Right now, in this economy, theater artists are operating very much in fear and isolation,” says Tresnjak. “Everyone is worried. It’s great that something like this brings all the theaters together.”

Concludes playwright Doug Wright, who will portray Kaufman onstage at the La Jolla Playhouse: “Often, we feel theater has become a kind of rarefied museum and no longer has cultural or social relevance. The fact that ‘The Laramie Project’ has been done in so many colleges and secondary schools means it has influenced and informed a whole generation about these issues.

“We don’t think that theater has the power to change the world, and I think Moisés’ plays prove other- wise.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.