Must Reads: An early Disneyland designer won over Walt Disney. Now he laments: ‘The park is gone’

Rolly Crump, who helped design many hallmarks of American pop culture as a Disney Imagineer, talks about his artistry.

Try as he might — and he’s tried countless times — Rolly Crump just can’t quit Disney. But his latest attempt may be the closest he’s come.

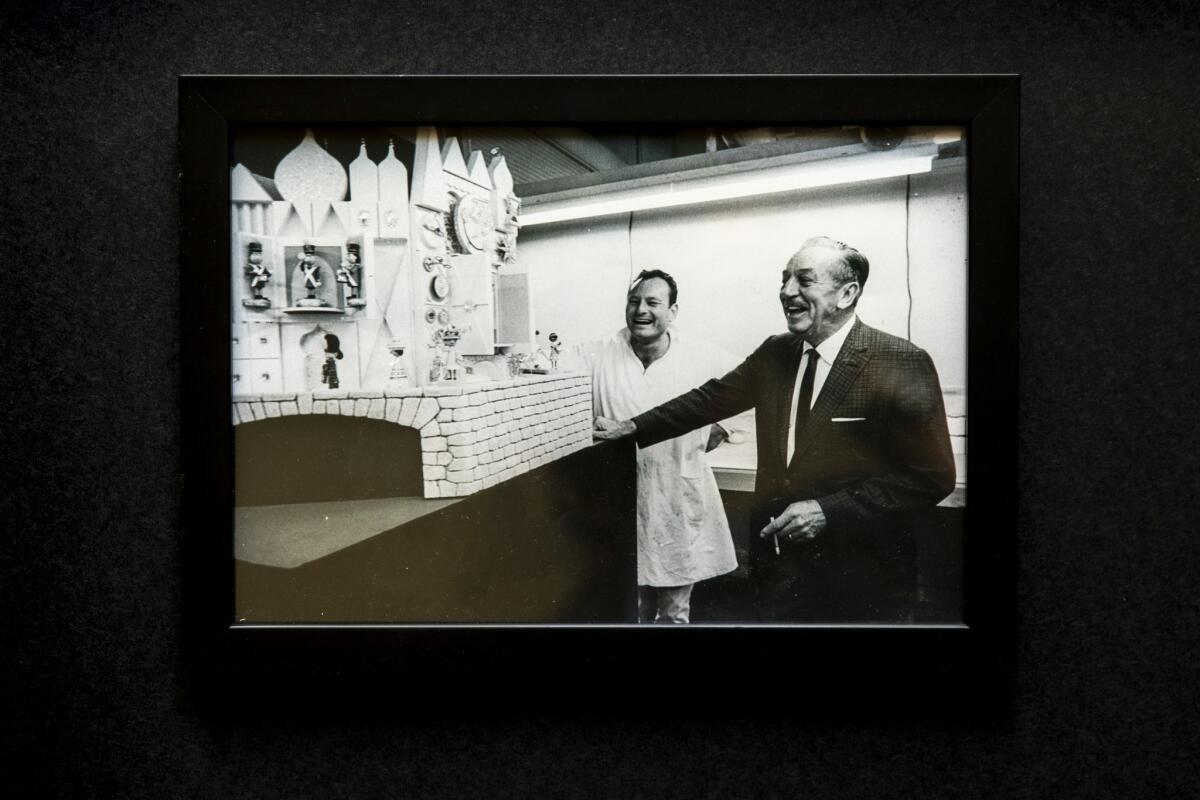

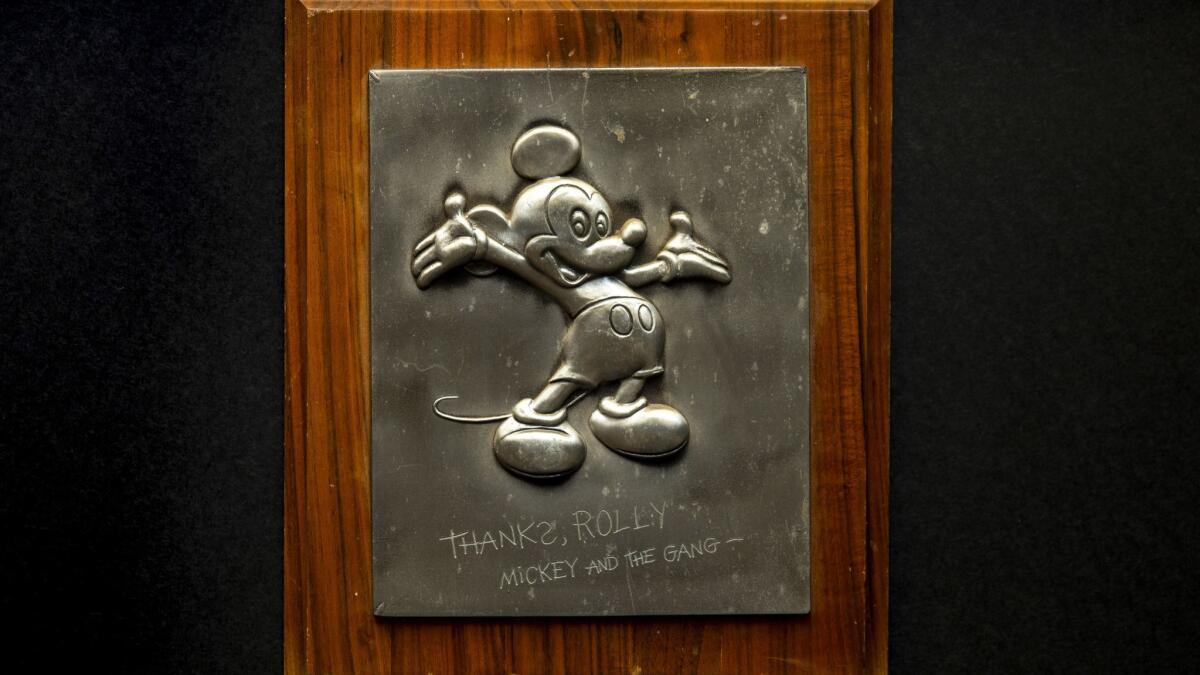

Earlier this year Crump had artifacts from nearly all of his life’s work auctioned off, a sale decades in the making that brought in more than $600,000. No surprise the items were in demand. In addition to having a hand as an assistant animator in the Disney films “Lady and the Tramp” and “Sleeping Beauty,” Crump’s resume just so happens to contain work on It’s a Small World, the Enchanted Tiki Room and the Haunted Mansion, cornerstones of Anaheim’s Disneyland and pivotal works in American Pop art.

Crump is one the most important designers in the development of early Disneyland — and one of only a few surviving architects of the park who can speak directly to the intentions of its creator, Walt Disney.

He also has a reputation as one of the park’s most vocal critics, and for decades has offered blunt assessments of Disney designs as well as his former peers — a no-nonsense, tell-it-like-it-is artist who is offended at the suggestion that others would be offended by his critiques. At the same time, Crump is fiercely possessive of Disneyland’s ideals and believes strongly in the theme park as a place of living art.

To those outside the secretive walls of Walt Disney Imagineering — WED Enterprises (for Walter Elias Disney) when Crump joined the division in 1959 — the 88-year-old designer’s reputation is that of a rebel, a fierce protector of individual freedom in the complex world of corporate art.

His office door was graced with a “smoke marijuana” poster, and he’s been known to brag about driving his Porsche around Fantasyland when he served as Disneyland’s art director, one of his many roles during his numerous stints with the company.

To this day Crump is heralded as co-leading what would be Disneyland’s greatest version of Tomorrowland, a sort of mod-like vision of future-past that opened in 1967. And the Disneyland Hotel’s wildly popular bar Trader Sam’s is steeped in the Crump influence, having being designed in his vision of tiki culture. He was also the creative force behind one of Disney’s most storied never-built attractions, the Museum of the Weird.

“For me, he’s one of the greats,” says former Imagineer Tom Morris, who retired in 2016 after more than 35 years with Imagineering. “I would mimic his artwork as a kid, not even knowing there was a Rolly Crump. There was just something I liked about the line work and the design of the tikis and the stage in Tomorrowland or parts of the Small World facade. I would just doodle those, and then later I found out Rolly was the guy who did all that, and I was like, ‘He was a god.’”

Wild and crazy days

Yet Crump certainly didn’t feel like a god during his initial stint at Imagineering — the first of three, not including the occasional consulting gig — after being hired as an animator at Disney when he was in his early 20s. Crump says he was later told by Ken Peterson, who was running the animation department when Crump arrived, that “what you showed us was the worst portfolio of anyone ever hired in animation.”

Crump’s love of all things Disney began early, as an adolescent in Santa Monica raised largely by a single mom — a secretary for 20th Century Fox — and whose daydreams were fueled by Disney’s “Silly Symphony” cartoons.

It’s Crump, whose odd and wacky tendencies led to the Small World facade, where a clock with a goofy smile...is at once welcoming and mysterious.

So he drew, and with nothing more than a high school portfolio — Crump never attended college — made his way into the Disney fold.

At WED Enterprises, he would become somewhat close to Walt Disney, or as close, perhaps, as one could — Crump to this day refers to him as “the old man.” But that came later. Crump says he spent his first three years as an Imagineer speaking nary a word to him.

“All I did was absorb,” Crump says. “I watched how everyone reacted to Walt, and the strengths and the weaknesses of the different guys. I studied Walt Disney and what it was like to work with him, but I wasn’t participating until after three years. That’s when I started talking. I learned that if you show something to Walt, it has to be something he hasn’t seen before.”

A beatnik about two decades younger than many of Disney’s other well-known early Imagineers, Crump cites large-scale sculptor Louise Nevelson and activist, provocateur and jazz great Josephine Baker among his primary influences.

“Josephine was wild and crazy,” Crump says, “so naturally I was attracted to that.”

Crump’s own art could appear erratic. “A diamond in the rough,” Crump says is how a superior once described him — his colorfully untamed drawings lacked the encompassing, epic-like feel of Claude Coats, whose skill at creating environments formed the backdrop of many of Disney’s key attractions, or the exquisiteness of Marc Davis, who had a knack for crafting characters that felt alternately realistic and exaggerated.

And yet it’s Crump whose odd and wacky tendencies led to the Small World facade, where a clock with a goofy smile, inspired by the drawings of Mary Blair, is at once welcoming and mysterious, a clear sign that visitors are somewhere other than the “real” world. Only Sleeping Beauty’s Castle more instantly says “Disneyland.”

“The thing that should be noted is Walt allowed all of these people to show their own style,” says Morris. “It wasn’t a big corporate guidebook or style guide. Walt allowed there to be a Marc Davis style, a Claude Coats style, a Mary Blair style and Rolly — Rolly is definitely one of the Disneyland styles.

“There were just these different styles that co-existed and that makes it more fun,” Morris continued. “It’s an interpretation. It was not like, ‘Here is the corporate stylebook and here is how it has to look because this is how it looked in the movie.’ Disneyland really had a handcrafted quality.”

Decisions for what could end up in Disneyland could be made in a single meeting, says Crump. He recalls an afternoon with Disney and three or four other Imagineers to discuss a restaurant destined for Adventureland. A light tiki theme was planned, and John Hench, whom Crump cites as a mentor, suggested that there be stuffed birds throughout.

“Then Walt said, ‘Disney does not stuff birds, John.’ Then someone else said, ‘They’re little mechanical birds.’ These are words in a little meeting, and this all of a sudden became the Tiki Room.”

For Crump, the conversation led to one of his biggest challenges, handed down by Disney himself. “Walt said, ‘If we’re going to have people waiting to go into this restaurant, I don’t want people standing in line. Design some tikis that talk to people while they stand in line.’ That was my assignment.”

Weeks of research, aided by anthropologist Katharine Luomala’s book “Voices on the Wind,” led Crump to the idea of tiki gods and goddesses – Pele, a fire goddess, Hina Kaluua, a mistress of rain. “I showed them to Walt and he said, ‘These are great. Let’s go with them.’”

One problem: When Crump arrived at the model shop, Blaine Gibson, the park’s go-to sculptor, told Crump no. Despite the assignment coming from Walt, Gibson didn’t have time for Crump’s project and was unmoved by Crump’s pleas. “I said, ‘Well, then who will sculpt these?’ Blaine said, ‘You will.’

“Everything was so goddamn naive,” says Crump. “You just did what it took to do it. I used a plastic fork from the commissary to sculpt the clay on the tikis that ended up in Disneyland. That’s beautiful.”

After Walt

That handcrafted quality described by Morris and epitomized by Crump’s fork-sculpted tiki gods is what he repeatedly worries is disappearing from the parks.

Since the death in 1966 of his idol, Walt Disney, Crump’s relationship with the Disney corporation has been in flux. Crump’s conflicted emotions only intensified in the years leading up to the opening of Florida’s Walt Disney World in 1971.

“It had no feeling of Disney,” Crump says of Florida’s Magic Kingdom, noting it lacked the personal touch of animators trained in a hand-drawn craft.

“It was a lot of good architectural pieces, but I looked at that and thought to myself, ‘What the hell is going on here?’ Disneyland has charm. Disneyland freaking hugs you and kisses you.”

He points to the height difference between California’s Sleeping Beauty Castle (77 feet) and Florida’s Cinderella Castle (189 feet) as an example of the change. “When you go to Disney World and you see the castle, you want to genuflect ... and that disturbed me.”

Even so, he took part in the initial look of the Florida park.

“I helped design the rides at Disney World, but we lost the charm,” he says. “You can’t have someone in charge that doesn’t understand the look that Walt had — the art was done by people in animation, and animation background painters. The whole thing fell apart. I quit.”

Disneyland has charm. Disneyland freaking hugs you and kisses you.

— Rolly Crump

Of course, he didn’t stay away long. Crump quit and went back numerous times, and even helped develop Walt Disney’s World’s Epcot, including a design for it that never came to be: “Eptot,” an area of Epcot that would be dedicated for young children.

But when Disney died, so too did one of Crump’s most personal projects — the so-called Museum of the Weird that Disney championed and Crump’s Imagineering peers did not. For Crump, it’s the one that got away.

The idea began to germinate when he first started at WED and was assigned to work on a never-built “Wizard of Oz”-inspired area. He spent months with Disney’s master illusionist Yale Gracey working out effects for the Haunted Mansion. Even now Crump can talk endlessly about his trippy take on a seance room for the Haunted Mansion, one that in his initial drawings contained a talking chair, a cauldron in a fireplace and demented, tarot-inspired flags.

As Crump toyed with Mansion designs on and off over the years, breaking away for a time to work on It’s a Small World for the 1964 World’s Fair, his drawings increasingly emphasized the macabre — a coffin that doubled as a grandfather clock, a doorway made of human bones, a woman dubbed the “mistress of evil” or a man-eating plant, the latter living on to inspire the Haunted Mansion’s wallpaper. During a presentation to Disney, Crump says his peers told him his ideas would be “too weird” for the old man.

Crump says he arrived at WED’s offices the following morning to find Disney in his chair. “The first thing he said to me was, ‘You son of a bitch,’” Crump says. “All that stuff you showed me yesterday? I couldn’t sleep.’”

Disney then declared to the staff, “We have a Museum of the Weird now.” The plan, says Crump, was to “collect weird things from all over the world and bring them to Disneyland.”

Whether the Museum of the Weird would have ever become a reality depends on whom you ask. Yet longtime Imagineering leader Marty Sklar, who died last year, said in an interview in 2015 that if Disney had lived the Museum of the Weird would have found its way in the Mansion.

But, says Crump, “Management didn’t like it. Walt passed, and he took the museum with him. No one else wanted to fool with it.”

Artists’ legacy

Today, Crump is protective of his fellow artists’ designs. When he discusses the Haunted Mansion, he refers to it as belonging to Yale Gracey and when he talks about It’s a Small World, it’s “Mary’s ride.” He says he has a number of Mary Blair’s original drawings for the ride’s dolls, which he didn’t auction. “Those are priceless,” Crump says. “This is history.” But Crump also has no patience for any additions or aspects to It’s a Small World that deviate from Blair’s work.

“I was given the job of kind of supervising It’s a Small World,” Crump says. “I knew it was only going to work if everything looked like Mary Blair. As far as I was concerned, this is a Mary Blair ride.”

Crump’s own legacy is preserved via a window on Disneyland’s Main Street, U.S.A. — an honor reserved for those who were key in Disneyland’s evolution. Ask him about it and he’ll tear up.

“When I worked at the park, I’d see the names on the windows, and they were all gods,” Crump says. “They were all old guys. Finally one day I became an old guy. That was a very special thing.”

But casually mention, say, the high-priced private Club 33, and prepare for a rant — “pretentious” and “stupid” are among the printable words.

“No one is trying to keep charm in the park, and I’ve had enough of it,” Crump says of the Disneyland of 2018. “This has been my whole life.”

Fall in love with Disneyland, and Disneyland can break your heart.

Which is partly why, despite Crump’s tough talk about wanting to clear his home of his Disney artifacts — “It just became cumbersome,” he says — he ultimately wasn’t prepared to say goodbye. He admits now that he tried to stop from crying when he saw his art boxed up while he sat at a dining room table.

“It really didn’t hit me until they took it up to Los Angeles to have the auction,” Crump says, sitting on the porch of the Carlsbad home owned by his wife, Marie Tocci. He’s still imposing today, his wide glasses and closely trimmed white beard hiding stern, forceful features. “When that happened, I began to miss it. And when I went to the auction, it was a killer — a killer. It was really emotionally scary.”

Before the auction at Van Eaton Galleries, which is quickly gaining a reputation as a wheeler and dealer of vintage Disney — Crump’s works were on display at the Oceanside Museum of Art. Crump says he debated donating many of the items instead to the Walt Disney Family Museum in San Francisco.

And, says Crump’s son, Christopher, 64, who followed in his father’s footsteps to work for Disney, “There was talk of doing a traveling version of the exhibit, but dad, well, he’s a control freak. It started to exhaust him. When this notion of selling everything came up, that sorted out a big question and a quandary of what he was going to do.”

The auction offered the sense of finality that Crump appears to have been after for much of the past 50 years.

Ask him if he misses visiting Disneyland regularly, and he answers emphatically: “No, no, no, no, no. Not anymore.”

Then he pauses, and says simply, “The park is gone.”

While there most certainly is a theme park at 1313 Disneyland Drive in Anaheim — Crump dismisses it as “Stroller Park” — he views its current state the result of a battle he’s long been fighting.

When he expresses a frustration with the parks, it’s not due to a lack of desire to change. (And it needs to be noted that much in Disney’s parks today are very much handcrafted and full of personality — see Animal Kingdom in Florida, the massive, mountainous sculptures of Cars Land or the recently added evil beaver on the Disneyland Railroad.)

What Crump laments is the obviously personal touch — an attraction that clearly belongs to a specific artist more than it does a blockbuster film. “That points to the question of what Imagineering did Rolly work for,” says his son Christopher, who recently retired but returned to consult on the revamp of Paradise Pier into Pixar Pier at Anaheim’s California Adventure.

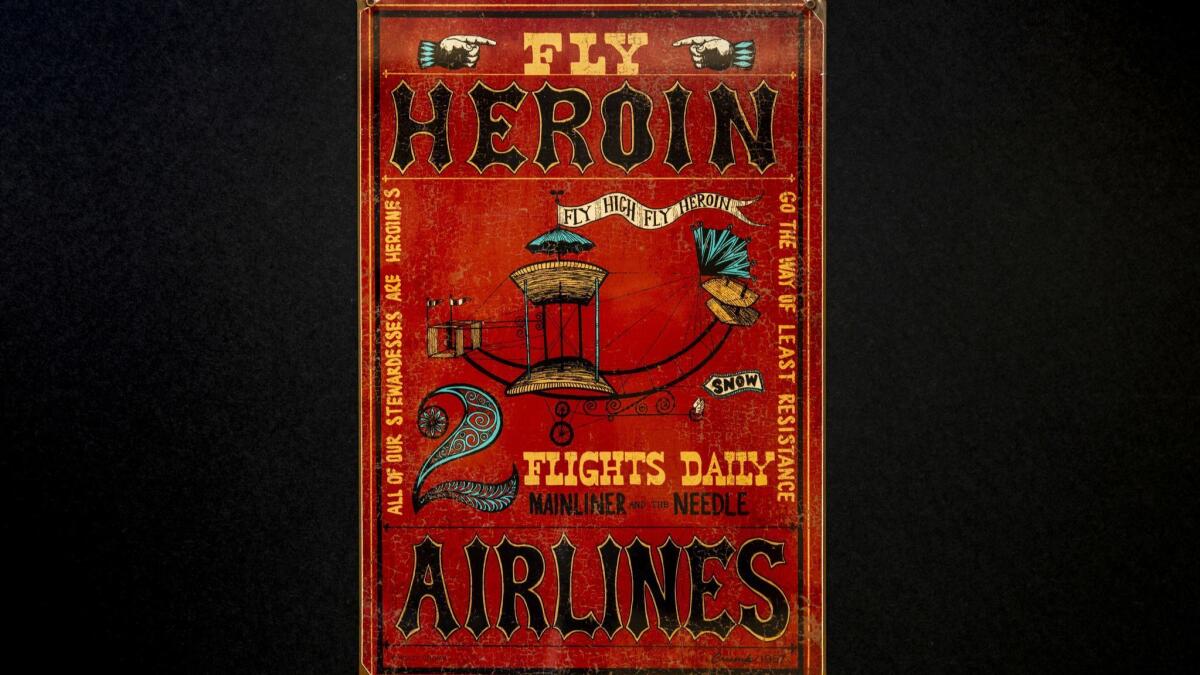

“If you wanted to think about his design philosophies and the guy he was — you’ve seen the beatnik posters and what he calls the dope posters — it was all counter-culture, and my dad dressed like a beatnik. But he’s a nut. They were all nuts.

“This was a brand-new endeavor for most of them,” Christopher continues. “They were making this up as they went along and there was a lot of experimentation. It didn’t matter if you hadn’t done it before because nobody had done this before.”

Crump’s outsider role was one he relished playing. This is a man, after all, who drew a naked and full-figured Rapunzel for Florida’s Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride. And to help make ends meet while working at Disney, he sold what he calls his “dopers,” art prints that celebrated illicit drugs as if they were circus attractions. It was one such poster that Morris saw when given a tour of Imagineering in the ’70s before going to work there full time.

“He was newly returned to WED and I met him in his office, and it had a giant ‘smoke marijuana’ poster on the front,” says Morris. “It was a big Disneyland-attraction-sized poster on his door, and I remember thinking, ‘This is an unusual place.’”

Remember, says his son, that the original Imagineers were “artists who don’t have to give a you-know-what about anything, people who say what they say because that’s what they think. That’s dad. He’s not going to tailor his opinion to make someone feel good. That’s a byproduct of a particular time, and a time in which he was extremely prolific. So that part of him hasn’t changed. That’s core Rolly.”

While Crump’s art was more whimsically outlandish than what Disney was known for, emphasizing bold and brash colors and an offbeat sense of humor — think work fit for a comic book, or better yet a tattoo — it was far from rudimentary.

And core Rolly had room for what some could perceive as imperfections. When it came to the Small World facade, Crump went above his boss, Richard Irvine, to go straight to Disney, as Irvine was seeking to have Davis redesign it.

“I showed the clock to Walt and Walt said, ‘That’s good.’ Dick said, ‘It doesn’t have that European flavor. I’m having Marc redesign it.’ Walt looked Dick straight in the eye and said, ‘I like it the way it is.’ The old man backed me on so many damn things. That’s why so many people didn’t like me.”

When Crump received his invite to become a Disney “legend” in 2004, he trashed the envelope, believing the company honor had become more about celebrity rather than saluting those who have shaped Disney history.

But he went, largely at the urging of his son and Imagineering executive Sklar. And then he proceeded to choke up onstage. “That’s my dad,” says Christopher. “He’ll say, ‘I’m not going to that goddamn thing,’ Then he always goes to that goddamn thing.”

Yet there’s no denying there’s a sense of visible relief in Crump no longer being surrounded by his decades of Disney and personal work.

Months before Disneyland opens what will be the largest expansion in its history — 14 acres dedicated solely to “Star Wars” — Crump simply hopes we don’t lose sight of what Disneyland once was, a place, in the words of his son, designed by “nuts.”

“I was part of all this stuff that had never been done before,” Crump says. “I’m proud of that. I feel real good about that. I knew what we were doing was very special, and I knew that we were the best.”

He then recalls one of his proudest moments, and it occurred at Club 33 — yes, the very place he dismissed as pretentious. Shortly after Tomorrowland’s revamp opened in 1967, Crump took the staff out to celebrate.

“We had a big lunch at the 33 club,” Crump says. “Roy Disney was there. Roy Disney came up to me and he said, ‘Are you Rolly Crump?’ I said, ‘Yes, sir. I am. ‘ He said, ‘My brother used to talk about you.’”

This is when Crump’s smile widens, a grin as big as a kid discovering a “Silly Symphony” for the first time. “I just thought, ‘That’s cool.’”

ALSO

Meet Disney’s philosopher king: the brain behind ‘Avatar’s’ Pandora and Marvel’s ‘Guardians’ ride

Digging up the ghosts of Disneyland’s Haunted Mansion ride

This is your brain on Disneyland: A Disney addict’s quest to discover why he loves the parks so much

Two Bit Circus will bring an indoor game-focused theme park to downtown Los Angeles

Follow me on Twitter: @toddmartens

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.