Great Read: The frog that jump-started Mark Twain’s career

Reporting from Angels Camp, Calif. — In the humble-looking notebook of a luckless prospector staying in a cabin on Jackass Hill near here in California’s Gold Country a century and a half ago, there’s an entry barely longer than a tweet.

“Coleman with his jumping frog — bet stranger $50 — stranger had no frog & C got him one — in the meantime stranger filled C’s frog full of shot & he couldn’t jump — the stranger’s frog won.”

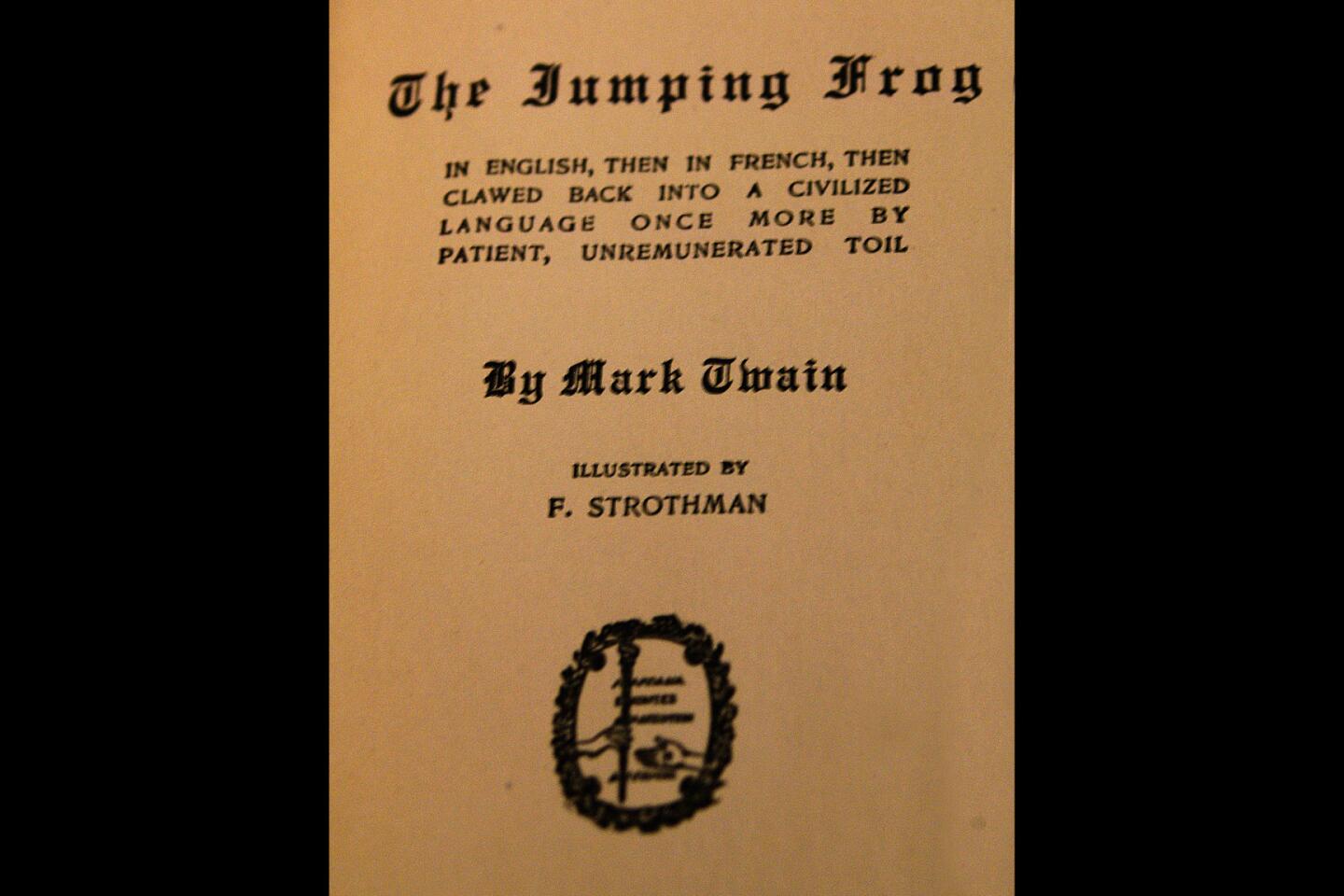

The passage is, of course, the literary skeleton of what down-on-his-luck Samuel Clemens would transform into literary gold, a wildly improbable story originally called “Jim Smiley and His Jumping Frog,” which introduced much of the 19th century world to Mark Twain.

Cleverly crafted by a Missouri transplant who journeyed west with visions of making his fortune in the gold fields of California, the story gave Clemens the strike he was looking for, but in a guise he’d never imagined.

Yet only in recent years has the significance of Twain’s time in the mother lode come into sharper relief, in particular the transformative role the friendships he developed here played in his decision to abandon youthful dreams of a career piloting paddleboats down the mighty Mississippi River and instead “excite the laughter of god’s creatures.”

That chapter in Twain’s life is about to be feted, as it is every year, in Angels Camp, the Calaveras County mining town where Twain first encountered the frog-jumping story. Thursday through Sunday, the town’s resident population of 3,836 will expand more than tenfold with the annual Calaveras County Fair & Jumping Frog Jubilee. Typically around 50,000, attendance is expected to surge this year because of extra attention on the 150th anniversary of Twain’s short story, published Nov. 18, 1865, in the New York Saturday Press.

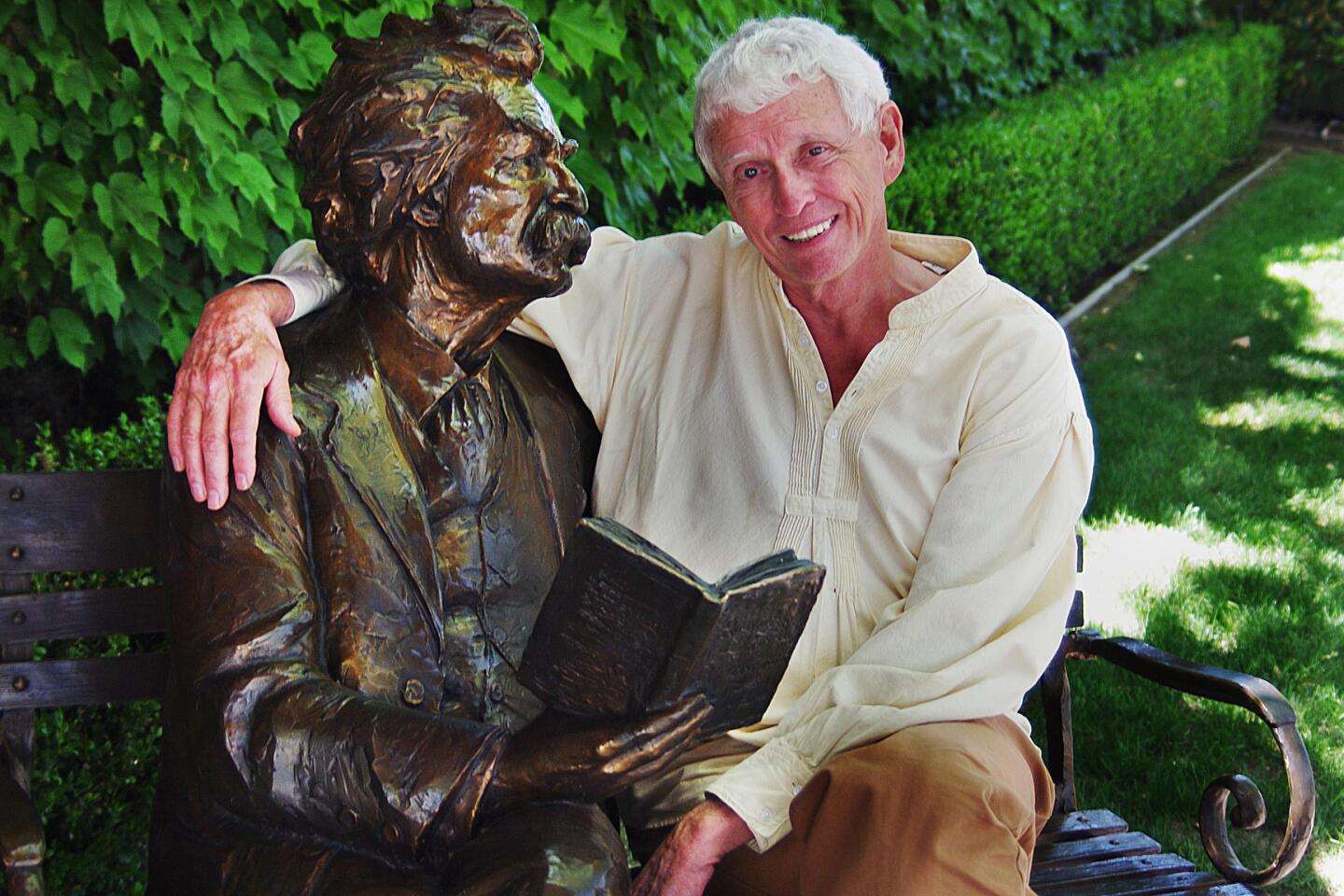

“People can explore gold mining in any number of places — they come here because of Mark Twain,” said Jim Fletcher, a retired middle-school English and history teacher who has taken on the title of “official storyteller of Calaveras County,” a role for which his snowy-white hair, high-pitched singsong voice and genially exuberant demeanor seem ideally suited.

The 88 days that Twain spent in the verdant, mineral-rich mountains just over 100 miles east of San Francisco in the rainy winter of 1864-65 are seen as a major turning point in his life — and career. Just five years later, Twain himself acknowledged that “right in the depths of [the miners’] poverty and pocket mining lay the germ of my coming good fortune.”

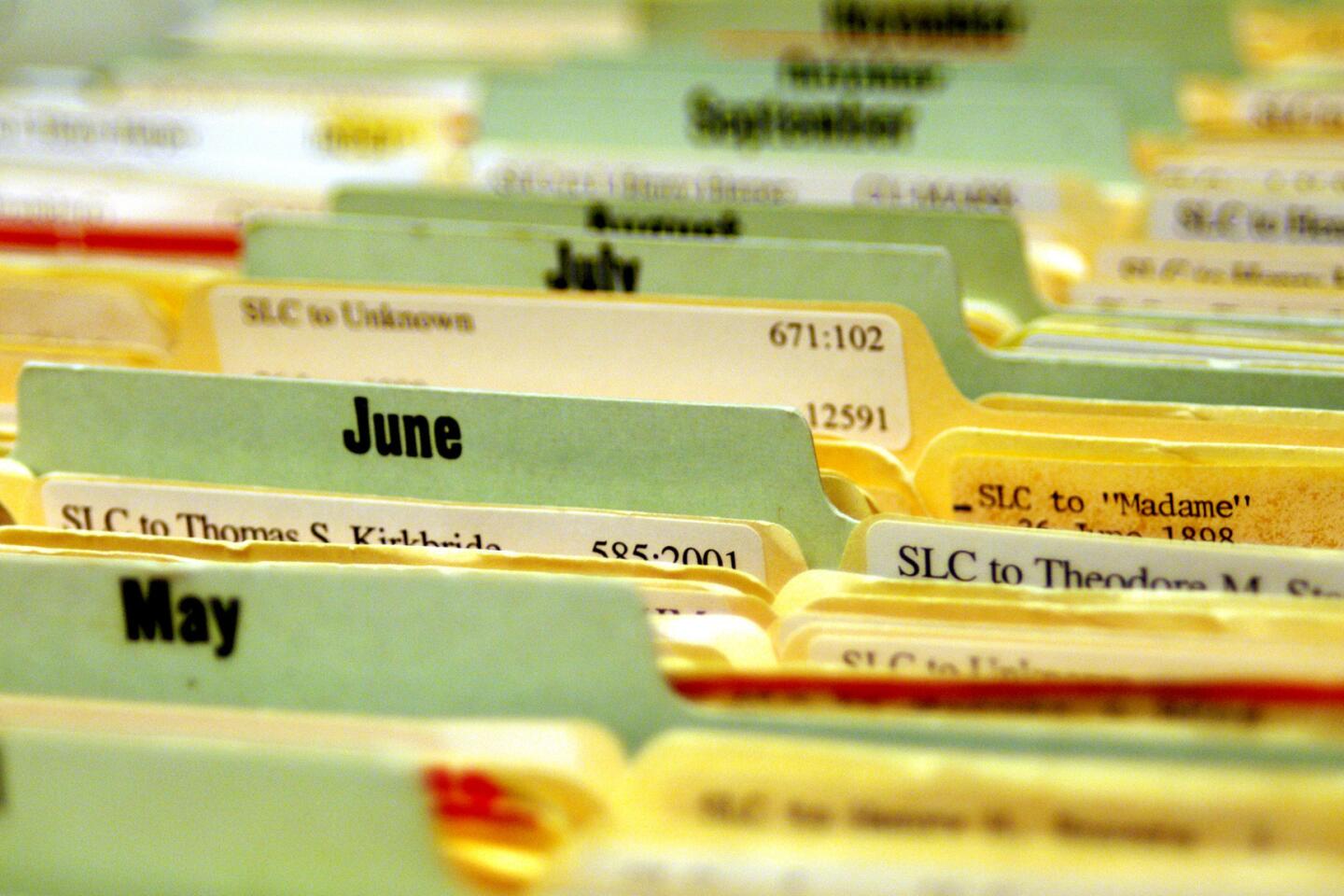

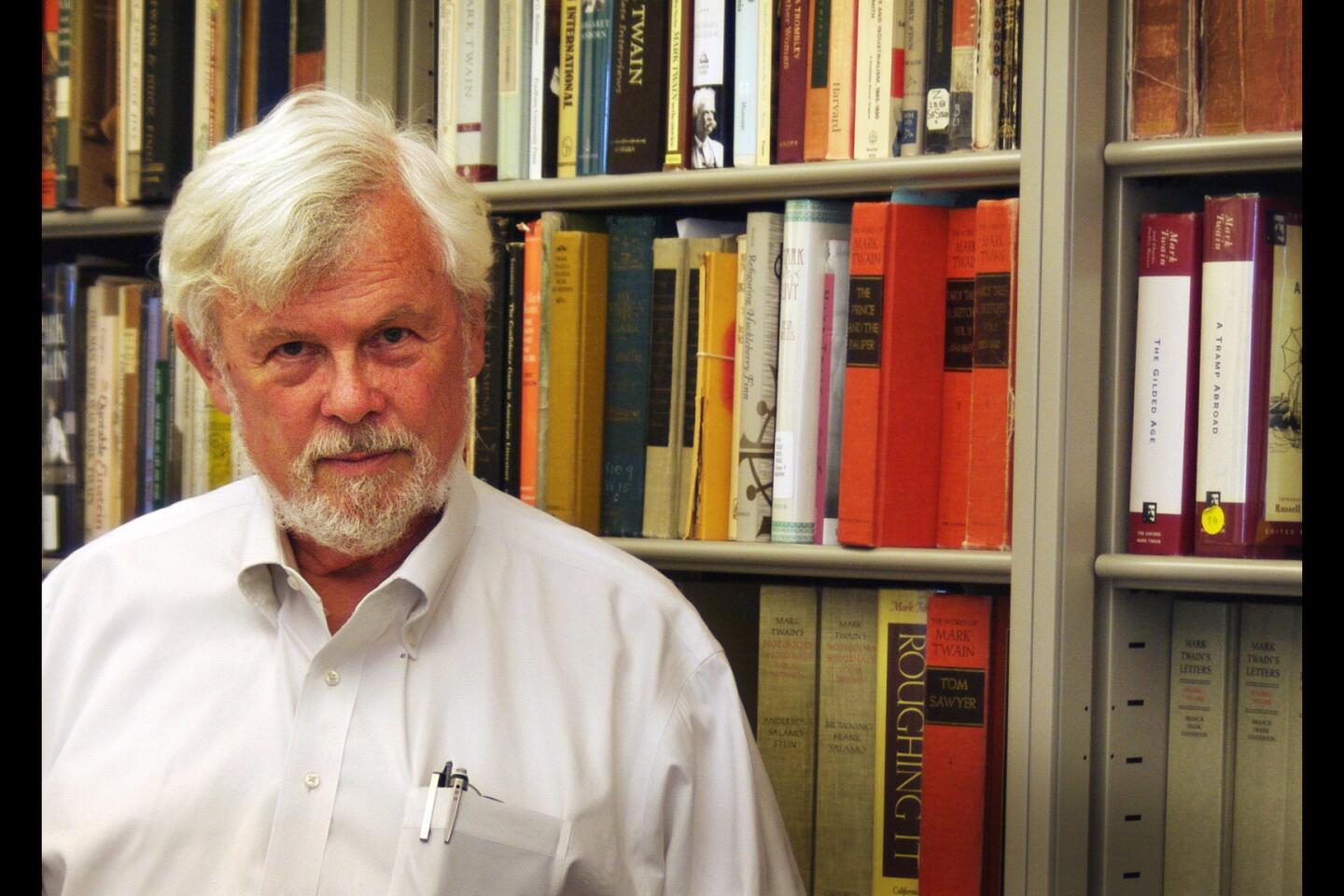

“He was at a juncture,” said Robert H. Hirst, general editor and official curator at the Mark Twain Project and Papers housed in the UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library, where he has worked intimately with Twain’s legacy since 1967. “Even when he’s in Angels Camp, he still has not made up his mind to make his career in literature. And he’s not going to make that leap until he is forced to, economically.”

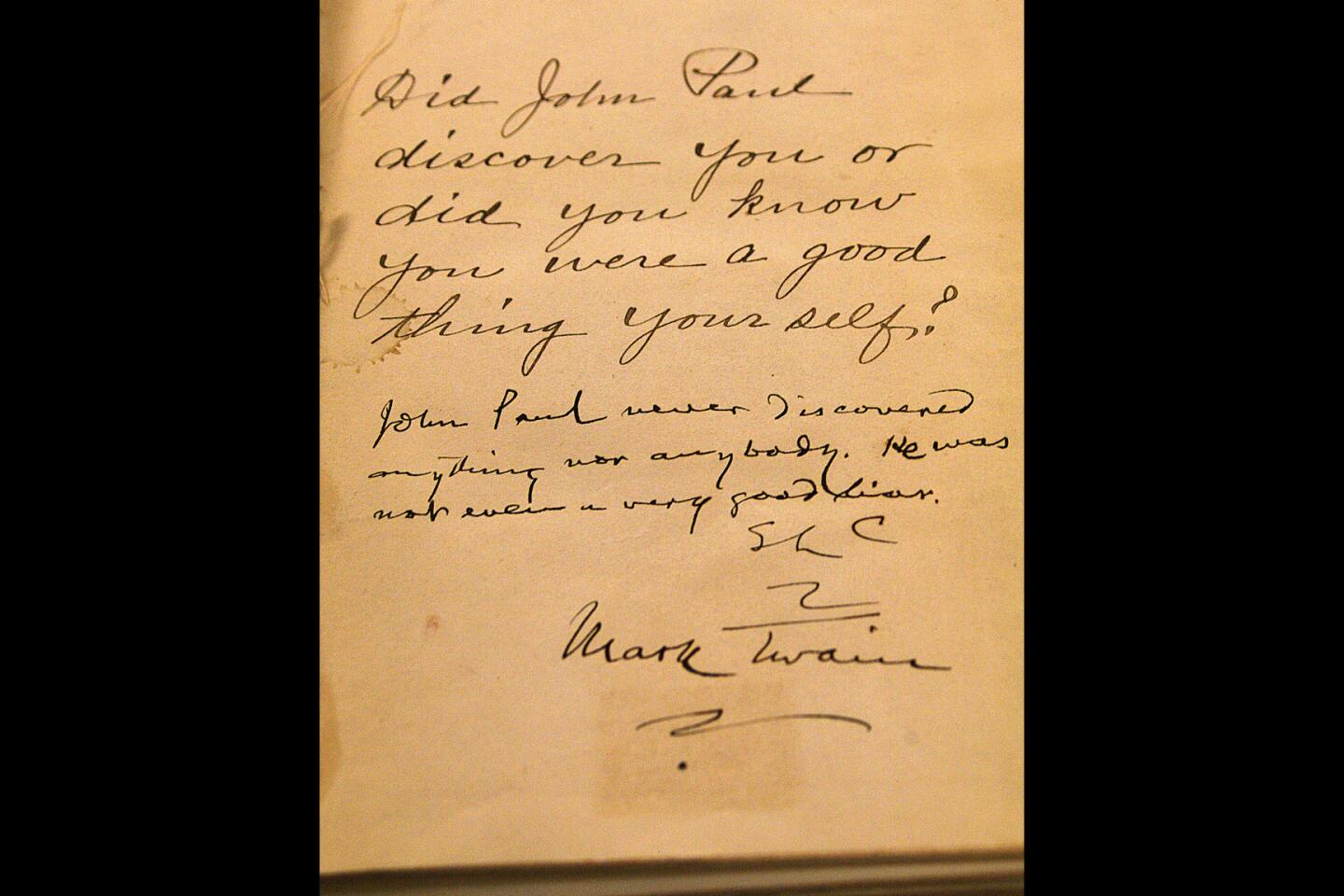

But in a letter from October 1865 — one of 2,700 housed in the library’s vault, just a fraction of as many as 50,000 letters Twain is estimated to have written during his 74 years — the writer outlines eloquently, even apologetically, the career direction he has decided on just shy of turning 30.

“I never had but two powerful ambitions in my life,” he wrote to his brother, Orion, and sister-in-law Mollie. “One was to be a [riverboat] pilot, & the other a preacher of the gospel. I accomplished the one & failed in the other, because I could not supply myself with the necessary stock in trade, i.e. religion.

“But I have had a ‘call’ to literature, of a low order — i.e. humorous,” he conceded. “It is nothing to be proud of, but it is my strongest suit.”

::

Over the next 45 years, such books as “Tom Sawyer,” “Roughing It,” “The Innocents Abroad” and his literary masterpiece, “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” were rooted in a new and distinctly American approach to humor, one in which Twain was schooled intensively by the circle of friends he lived among in the mining camps of Northern California.

Only when he had run out of money and other career options did Twain fully embrace his literary talent. He began searching for something to fulfill a request from humorist and lecturer Artemus Ward for a book of western experiences he was planning to publish, resurrecting the yarn he heard in Angels Camp. But it arrived too late, so Ward’s publisher sent it to the Saturday Press.

“I think of that as the crucial element,” Hirst said, “and I don’t think he would have reached that conclusion quite the way he did if it hadn’t been for this moment [in mining country] away from all the pressure.... He’s not having to worry about earning a living. He’s messing around with pocket mining, and he listens. One of the key things about that notebook is that anecdotes he writes down in it appear in his work forever.”

That journal — “Notebook No. 4,” as it’s commonly referred to among Twain experts — shows he first heard the frog story in Angels Camp, about 10 miles north of Jackass Hill.

In the notebook, Twain often grouses about subsisting on “beans and dishwater” and the frequent rain and snowstorms in December and January, yet later in life he remembered that period as a “serene and reposeful and dreamy and delicious sylvan paradise.”

He was staying in a ramshackle cabin owned by Jim Gillis, the eldest brother of Twain’s friend and fellow newspaperman at the Virginia City (Nev.) Territorial Enterprise, Steve Gillis.

Jim Gillis was a well-educated, articulate — and funny — man. He regaled Twain and others who gathered in his cabin or the barroom in Angels with tales he fabricated on the spot, along with his recitations from “Byron, Shakespeare, Bacon, Dickens & every kind of only first class Literature,” according to Twain’s journal.

Another entry says he and Gillis, who remained friends for life, goofed around during dinner one night “talking like people 80 years old & toothless.”

Twain marveled at Gillis’ deadpan delivery — a style he would soon emulate with great success when he took to the stage in 1866.

It’s not something Twain spent much time expounding on in his own writing. But in 1899 he did write a piece titled “How to Tell a Story” delineating the difference between the new American brand of humor from that of its European counterparts.

“There are several kinds of stories, but only one difficult kind — the humorous,” Twain wrote. “The humorous story is American, the comic story is English, the witty story is French. The humorous story depends for its effect upon the manner of the telling; the comic story and the witty story upon the matter.”

The work of singer, songwriter and composer Randy Newman often has been compared to Twain’s writing for its ironic humor, biting political and social commentary and the frequent reliance on a narrator whose perspective is anything but omniscient and unbiased.

“I’m sure he’s had an influence on my work,” Newman said. “In Europe, there was Cervantes, and we were sort of supposed to know that a narrator, and not only the hero, is badly off. But it certainly was a whole new thing he brought.”

::

The intertwined historical legacies of the tale most widely known as “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County” and gold mining are impossible to escape 150 years later in Angels Camp.

A short stretch of three blocks of downtown Main Street has its own walk of fame — technically, it’s the Angels Camp “Hop of Fame.” Bronze plaques set into the sidewalk commemorate the name of each frog that’s won the jump since the 1920s — names such as X-100, Johnny Jumper, Can’t Take It and The Pride of San Joaquin — with statistics on the length of the winning leap and each frog wrangler’s name.

And there’s Fletcher, who entertains and educates audiences about Twain’s life every Wednesday in the warmly decorated Mark Twain Library at Camps Restaurant, a short drive from downtown Angels Camp.

He calls his weekly talk “88 Days in the Mother Lode,” a title he’s also using for a short book due to be published next month.

Through those talks he met actor, musician and filmmaker John C. Brown, who lives in nearby Sonora, and who has assembled a low-budget documentary of the same title that’s been making the rounds at film festivals, is available on Amazon and is on track for PBS exposure this fall.

Brown noted that the Angels Camp experience is often brushed away quickly — “and then he spent three months in the mining camps” — before moving on to other biographical details of Twain’s life. But that is changing.

“There is now a wonderful energy about Twain and his importance to our town,” Fletcher said. “The 150 celebration will change everything in our town for the better and, hopefully, supply a much richer and educationally rewarding visit to our community.”

Fletcher doesn’t put much stock in what appears to be a suicide threat in the same letter, revealing the desperation that led to his decision to focus on humor writing. “You are in trouble, & in debt — so am I,” Twain wrote to his brother. “If I do not get out of debt in 3 months — pistols or poison for one — exit me.”

Some media outlets have pounced on that sentence as a refutation of his long-cherished persona as the carefree sage dispensing pearls of homespun wisdom. Once again, the evidence is Twain’s notebooks — not necessarily the content but the very act of keeping them.

“A notebook,” Fletcher noted, “is something needed by a person with a future.”

ALSO:

Lost Mark Twain stories recovered by UC Berkeley scholars

Scientists get schooled at Calaveras County frog-jumping contest

Nevada newspaper where Mark Twain made his name is back in business

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.