In ’12 Years a Slave,’ Steve McQueen juxtaposes beauty, brutality

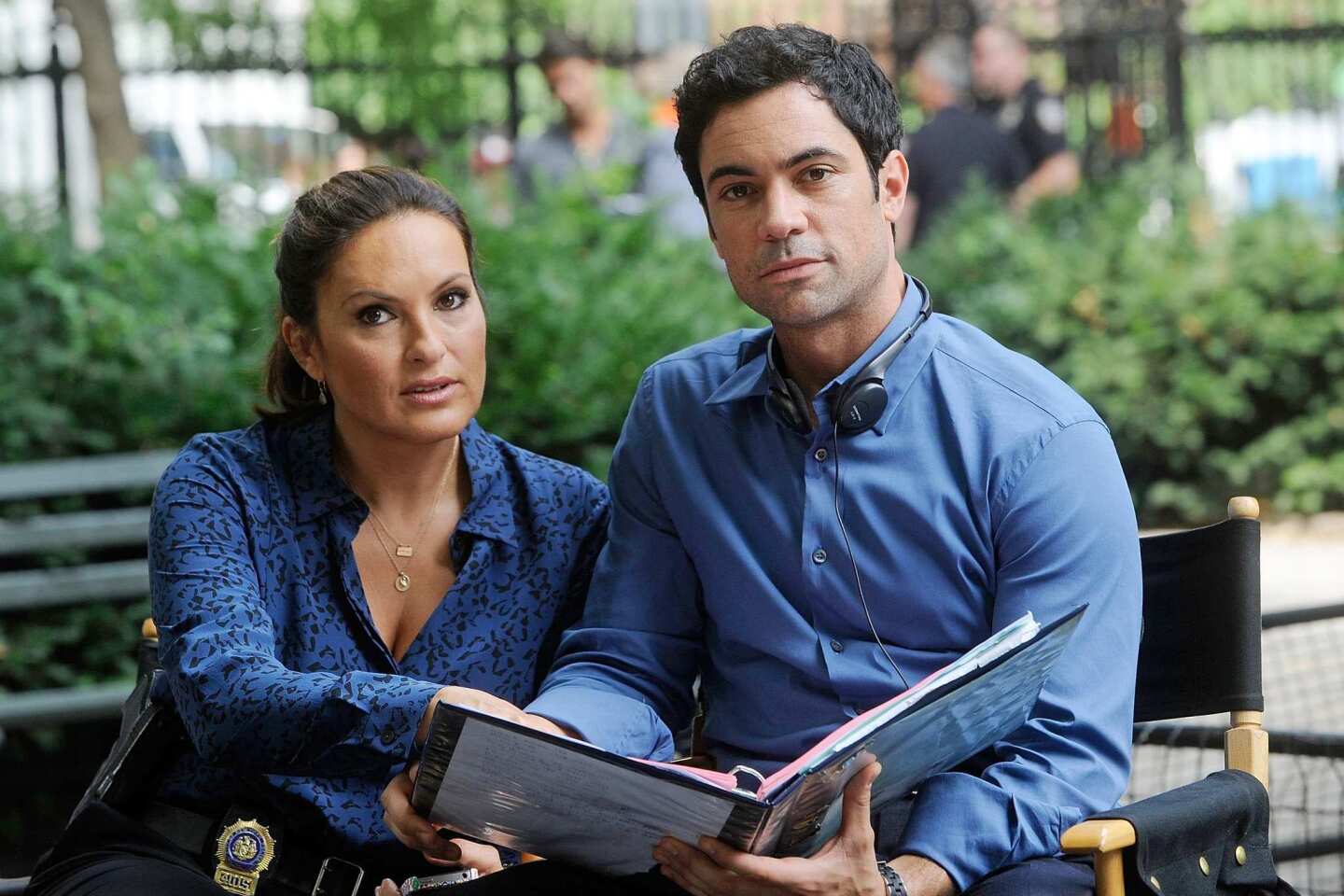

TELLURIDE, Colo. — Many sequences in Steve McQueen’s new movie, “12 Years a Slave” — the true story of a free black man kidnapped in 1841 and sold to Southern plantation owners — were emotionally exhausting to film. But the British director didn’t fully appreciate how wrenching the shoot was for his actors until he was in the editing room, scrutinizing the footage of a rape scene.

Michael Fassbender, playing a particularly despicable slave owner named Edwin Epps, was violating his most prized cotton-picking possession, Patsey, played by newcomer Lupita Nyong’o. McQueen’s camera was pressed close to Fassbender’s face as the actor whipsawed between tenderness and violence, alternately cooing to and choking his victim.

At the end of the sequence, McQueen saw in the editing room, Fassbender crumpled. The actor, McQueen realized, had momentarily passed out.

“That’s how focused he was in that scene, in that situation,” McQueen said at the Telluride Film Festival, where the movie had its world premiere last week. “There was nothing left.”

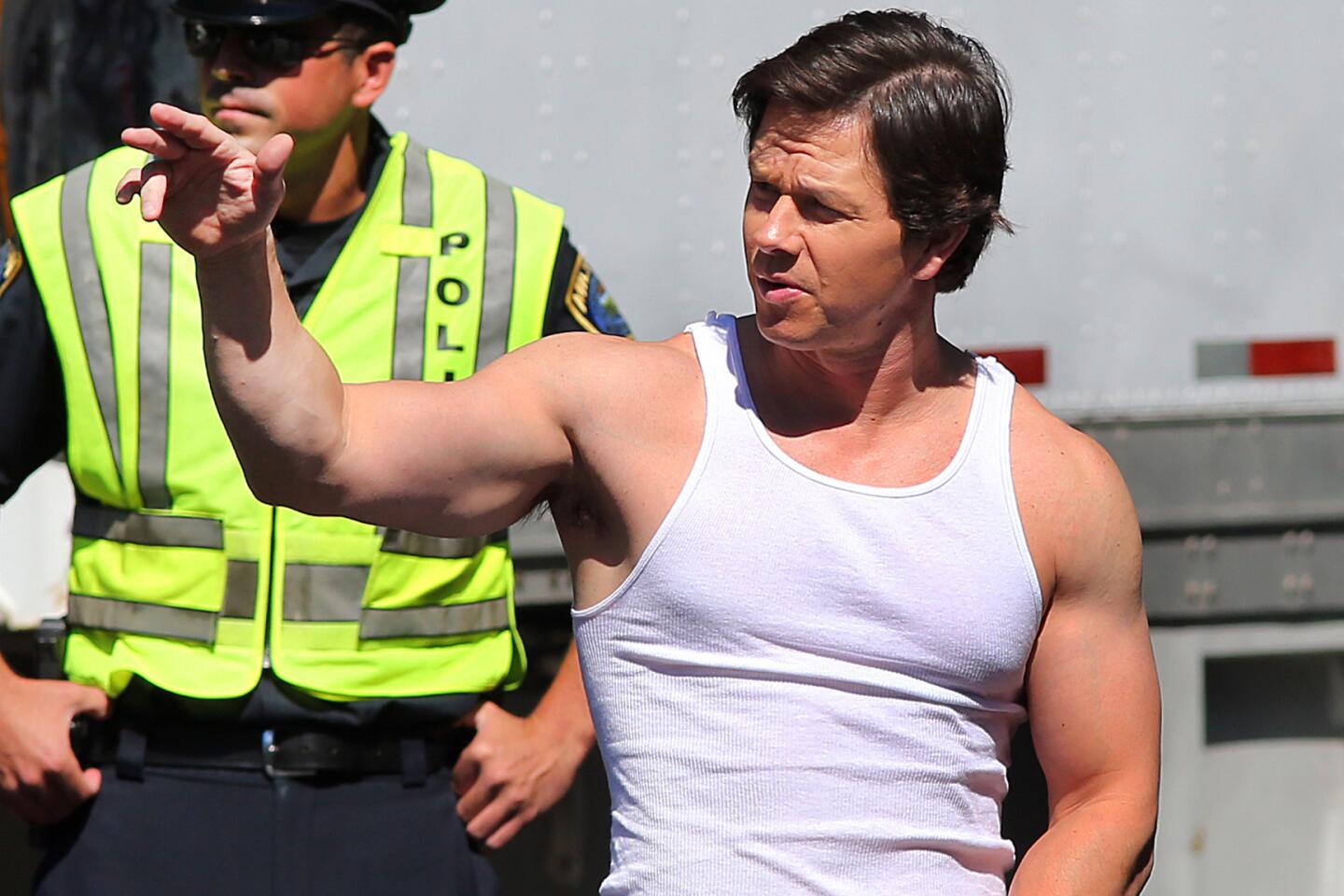

PHOTOS: Telluride Film Festival 2013

Opening in limited release Oct. 18 after playing at this weekend’s Toronto International Film Festival, “12 Years a Slave” is as difficult to watch as it is lovely to behold. Starring London-born Chiwetel Ejiofor as the former freeman Solomon Northup, the movie received several standing ovations at Telluride and looks like a strong Oscar contender, as long as audiences can see its beauty amid the brutality.

“It is about beauty — those plantations are beautiful,” said McQueen, whose first two features, “Hunger” and “Shame,” were stark, haunting looks at difficult, dark subjects. “And the juxtaposition of what happens there.”

Ejiofor’s gripping performance is rooted in the reality of Northup’s nightmarish tale, originally told in his 1853 memoir.

WATCH: Trailers from Telluride

Born in Minerva, N.Y., he was an educated musician and married father of two young children when he met a pair of promoters who said they intended to advance his violin playing in Washington, D.C. Instead, he was drugged, and when he awoke, held prisoner. Soon, he was shipped by boat to New Orleans, given a new name — Platt — sold for $1,000 and enslaved by a series of owners, culminating with Epps.

All that separated Solomon from freedom was pen and paper: If he were able to write and send a letter to the North, his hopeful thinking went, his family would quickly send for him, and he would be released. But even obtaining those instruments, as the opening minutes of the film make clear, was nearly impossible.

Slavery stories

“12 Years a Slave” arrives as a new wave of filmmakers and authors is wrestling with and reexamining that painful chapter in U.S. history. Quentin Tarantino’s “Django Unchained” cast Jamie Foxx and Christoph Waltz last year as a freed slave and a bounty hunter exacting vengeance throughout the South. And last month, James McBride published “The Good Lord Bird,” an acclaimed novel about the abolitionist John Brown.

Though “12 Years a Slave” may seem like a quintessentially American story, McQueen and Ejiofor say the international pedigree of the cast and production (Fassbender is Irish-born, and Nyong’o was born in Mexico and raised in Kenya) is unremarkable. John Ridley, an African American screenwriter, adapted Northup’s book, and Brad Pitt’s production company was instrumental in bringing the project to life.

“It’s international, really, as was slavery,” said Ejiofor, whose parents are Nigerian. “We’re artists — our nationalities don’t matter,” added McQueen, who is of Grenadian descent.

Pitt’s production company, Plan B, became eager to work with McQueen after the 2008 release of “Hunger,” a grim account of the 1980s hunger strike by IRA prisoner Bobby Sands (played by Fassbender). “We banged on his door, and we banged on his door again,” Pitt said.

INTERACTIVE: From Toronto to the Oscars? Well...

Pitt and his partners Dede Gardner and Jeremy Kleiner asked the filmmaker, then not even 40, what he wanted to do next. McQueen was about to make his sexual addiction drama “Shame,” also starring Fassbender, but was eager to follow that with a film about slavery.

“He said, ‘Why have there been 57 movies about the Holocaust, but there’s hardly been a movie about this?’” Pitt recalled. Gardner replied to McQueen: “We don’t know. But why don’t we try?”

McQueen was interested in following a character’s journey from freedom into slavery rather than telling a more conventional liberation tale. “The notion of someone who had his freedom taken away was always more compelling to him,” Gardner said.

The source of such a tale proved elusive, though, until McQueen became acquainted with Solomon Northup’s memoir, which was published just months after abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

Though hardly as influential as the bestselling “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” the memoir helped shape the anti-slavery debate. However, it went out of print for decades and was little-known until an academic from Louisiana, Sue Eakin, brought attention to it in the 1960s.

“It was very difficult to get the book,” McQueen said. “But as soon as I put it in my hands, I couldn’t put it down. It’s a firsthand account, just like ‘The Diary of Anne Frank,’ but 100 years earlier. I said, ‘This is the movie I want to make.’”

The appeal of the 229-page book, which is now widely available and taught in some Southern high schools, was obvious.

Though told dispassionately, the memoir overflows with vivid incidents — families ripped apart at auctions, attempted escapes, beatings, hangings and whippings. Repeatedly, Solomon must hide his intelligence from his masters, lest it be used against him. And yet his intellect compels him to strike back at one overseer (played in the film by Paul Dano), as his well-founded sense of righteousness is not initially tempered by the reality of his predicament.

PHOTOS: Venice Film Festival 2013

In adapting Northup’s book, Ridley (“Red Tails,” “Three Kings”) and McQueen invented hardly anything, compressing some early scenes and then selecting from a litany of horrors the most powerful material. The film gives Patsey a more prominent role and makes her flogging the centerpiece of the film’s conclusion.

And yet, as the autobiography’s title makes clear, Solomon’s captivity eventually comes to an end — thanks to an itinerant Canadian carpenter named Bass (played by Pitt) who considers slavery “all wrong, all wrong” and is willing to take a great risk on Solomon’s behalf so that justice might be done.

“We think it’s something we’ve dealt with and debated — we fought a war over it,” Pitt said. “But it’s not until reading Solomon’s story that you really understand what it is to take someone’s freedom and tear apart a family. It illustrates man’s inhumanity to man, but it also reminds us of our responsibility to each other.”

True intensity

When McQueen first asked Ejiofor to play the lead role, the veteran of “Children of Men” and “Dirty Pretty Things” demurred. After reading the screenplay, the actor felt he needed some time to consider what he would be undertaking.

“It was too soon,” Ejiofor, 36, said. “I needed to take a moment to think of what it would involve. In order to play that part, I knew where I would have to get to — to do Solomon justice — where you could feel, even for a moment, the total absence of humanity, of that pain and sorrow and sadness.”

Some 24 hours later, he told the director he would be his Solomon.

Having worked with McQueen before, Fassbender was prepared to take Epps into some dark and disturbing places, and the actor searched for tiny tethers of empathy to keep the sadistic character from disappearing into complete evil.

In short, Fassbender plays Epps as someone overwhelmed by his circumstances, an unjust man who also sees his situation as unfair.

“I tried not to make him too evil — I tried to find a human being there,” Fassbender said. “It’s very clear that he is falling in love with Patsey. He loves her spirit, he loves her physically — he just finds her very impressive. And he’s envious of Solomon. There’s something unnerving about him. There’s something out of the ordinary, but he can’t put his thumb on it.”

Filming on the $22-million production took place in Louisiana last summer, and the first day brought oppressive humidity and temperatures that reached 108 degrees.

“We were out there in the field, picking cotton — it was out of this world,” Ejiofor said of the heat. “You get a very visceral realization of what people were going through. We were lucky in a way that that was our first day, because it put us in the right mind-set.”

That mind-set was an extraordinary combination of splendor and sorrow.

McQueen and cinematographer Sean Bobbitt, who shot “Hunger” and “Shame,” framed their actors in the Southern locations as if they were formally composing portraits. “It may not be pretty,” said Ejiofor, “but it is beautiful.”

PHOTOS: Fall movie sneaks 2013

Nevertheless, McQueen didn’t intend to make “12 Years a Slave” easy viewing. So that the audience can’t avert its eyes or take a breath, he shot an extended whipping scene in a single take of more than four minutes, adding through visual effects grisly mists of flesh coming off the victim’s back.

And in editing the film, McQueen recast the film’s opening act, so that Solomon begins the film in hopeless captivity, rather than as an untroubled freeman. “You need to throw the audience into the deep end,” the director said.

Given the subject matter, McQueen and the film’s producers tried to create a set that was both reverent and relaxed. “I think the camaraderie is key — we had lots of fun together — because of what we had the next day in shooting,” McQueen said.

Even though they were telling a tale based on actual events, the cast and crew were at times caught off guard by reminders of what had unfolded on the very land on which they were filming.

In the shadows of one tree used for a “12 Years a Slave” lynching scene, the filmmakers found the graves of real runaways who had been hanged at that very spot more than a century before.

“To be sure,” said McQueen, “we were dancing with ghosts.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.