Amid the accolades, Kendrick Lamar refuses to compromise his vision, keeping it homegrown

About four hours ago, Kendrick Lamar woke up to the news that the Golden Globes nominated him for its original song in a motion picture prize, honoring “All the Stars,” his collaboration with SZA from the soundtrack to “Black Panther.” The next day the Compton rapper would discover that he’d be up for more Grammys than any other artist, eight total, including song of the year, record of the year and album of the year. All of them laud his work masterminding the platinum soundtrack to the $700-million-grossing Marvel Comics blockbuster.

You’d expect a faint hint of jubilation, or maybe much-deserved flexing from the only rapper to ever win the Pulitzer Prize. Inevitably, celebratory feasts will come later; proclamations of greatness will be commemorated on wax. But in the moment, Lamar, the consensus choice for greatest rapper alive, is completely even-keeled, even reserved. He introduces himself as “Kenny”: soft-spoken, head bowed, moving with hyper-focused swiftness.

It’s just another Thursday afternoon in Los Angeles. Promotional obligations are being fulfilled. The promise of Hollywood accolades to come isn’t an ego-sating notch as much as a symbol of what can be achieved.

“It feels great. I’m not only representing myself, but I’m representing my people … people I’ve been familiar with since I was born,” Lamar says in a conference room at The Times’ El Segundo offices, overlooking the cars zooming past on the 105 Freeway.

It’s only a few miles from the traffic-slammed interchange famously rendered in the first scene of “La La Land,” but Lamar reflects the diametric opposite of those transplant strivers. He didn’t have to try to save jazz; he artfully embodied its spirit (and in the process helped blow up South Central and Inglewood virtuosos Thundercat and Kamasi Washington). The 31-year old Lamar is steeled by an unbreakable covenant with the Compton soil and culture that raised him.

This is another landmark, another stepping stone to something bigger and greater. Best believe I’m proud.

— Kendrick Lamar

“This is another landmark, another stepping stone to something bigger and greater,” he adds. “Best believe I’m proud. And I know Ryan is as well.”

The Ryan in question is Ryan Coogler, writer and director of “Black Panther,” who recruited Lamar to helm the original soundtrack to his Marvel Cinematic Universe debut. The parallels between the pair extend well beyond being of similar age, creative temperament and socioeconomic background. They’re foundationally rooted in the independent tradition, which they transcended to become Trojan horses within pop culture at large. Thriving within the most rarefied strata of mainstream consciousness, Lamar and Coogler refuse to compromise their core vision and allegiances to the communities that irrevocably molded them. They’re beloved in both the ’hood and Hollywood.

“Our initial bond came from being from California and having similar backgrounds and stories,” Lamar says, highlighting Coogler’s Oakland roots. “In our first conversation, he told me about how [the film] was centered in the Bay Area. I’d never heard anything like that, as far as for a film in the Marvel universe. I was immediately all in.”

“Homegrown” crops up frequently in a conversation with Lamar. He uses it to describe both himself and Coogler. It’s a linguistic crutch, but accurately characterizes their work. In his debut feature, 2013’s “Fruitvale Station,” Coogler captured an impromptu New Year’s Eve BART dance party to the strains of Vallejo hero Mac Dre. In the big-budget “Black Panther,” Too Short’s classic “In the Trunk” opens the film. Lamar’s career is similarly full of strictly-for-the-real-ones moments. Take “King Kunta” from 2015’s Grammy-winning “To Pimp a Butterfly,” a funk anthem of black liberation that takes inspiration via a deep cut from Compton icons DJ Quik and his fallen protégé, Mausberg.

“There’s always that undertone of the homegrown [in Coogler’s work],” Lamar says. “Even if he’s not confronting you with it, it’s something that’s still there. And that’s something I can appreciate … someone who never forgets what inspired them.”

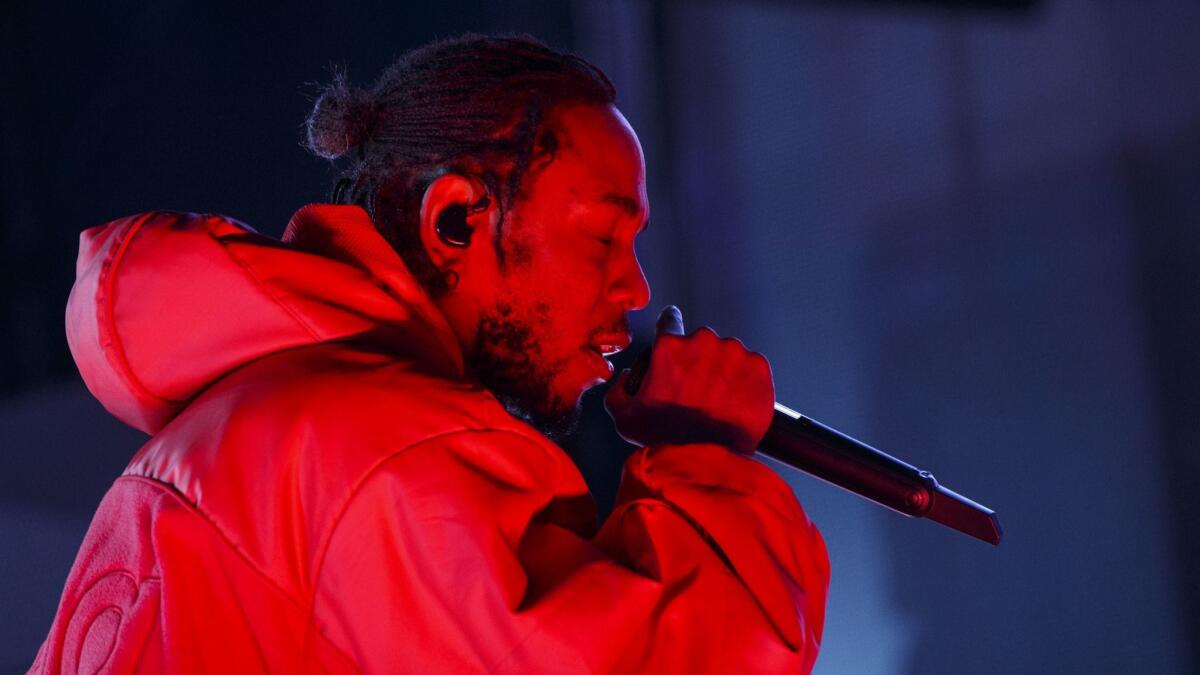

Lamar wears a black zipped-up windbreaker, dark pants and a gray argyle hat slung so low that it almost blocks all eyesight. During a photo shoot, a request to smile goes unmet, as though it would require the jaws of life. He’s livelier in conversation but still guarded, which you’d expect from someone whose offhand statements are analyzed with Talmudic scrutiny. When asked about new music, he demurs — claiming that he’s merely been jotting down thoughts, ideas and questions.

When prodded about what questions he’s asking, he cagily quips: “That’s personal.”

All political talk is ruled off the table. He’s friendly but cryptic, inclined toward vague generalities open to interpretation. He’s been writing long-form, but declines to articulate what it’s about, what themes are reoccurring and in what form it will eventually see release. He claims he hasn’t been working on a new album, but says that he’s constantly working. Someone in his camp mentions they’re going to the studio immediately after this.

Mostly, he’d prefer to discuss the importance of “Black Panther.”

“It was something I dreamed of as a kid,” he says. “A superhero who looked like us, talked like us and liked the same music.”

The proposition to collaborate came from Coogler toward the end of Lamar’s “DAMN” tour. Working closely with TDE in-house producer Sounwave and the label’s chief executive, Anthony “Top Dawg” Tiffith, Lamar and company wrote roughly 80% of the ideas for the hooks and beats for the film after two-hour nightly arena sets. To spur their inspiration and ensure stylistic coherence, Coogler frequently showed them new scenes from the film.

After rough skeleton tracks were completed, Lamar and Sounwave brought them to the guest artists, explaining the vibes and sonics that they aspired toward. The finished tracklist doubles as a litany of Lamar’s favorite contemporary artists: 2 Chainz, Swae Lee, SOB X RBE, Vince Staples, Jorja Smith, James Blake, Anderson .Paak, Future, Mozzy, Travis Scott and the Weeknd. His TDE brethren Schoolboy Q, Ab-Soul and SZA appear too — the latter delivering a bravura hook on the album’s hit single, “All the Stars.”

“I just didn’t want to do … that was corny just because there were certain names behind it,” Lamar notes. “I wanted to make it feel good for me and the listeners.”

He stresses the need for a connective tissue to the film, invoking canonized ’90s hip-hop film soundtracks like “Above the Rim” and “Menace II Society.” And it’s difficult to remember a rap anthology since the early Clinton years that so closely and effectively mirrored the cinematic ambitions. There are African tribal drums and lyrics about ancestral kings and heavy crowns. “Seasons” is sung entirely in Zulu. Straight from the East Bay, SOB X RBE trades frantic verses with Lamar about paramedics in the streets. On “King’s Dead,” Future freaks it and interpolates Three Six Mafia at the same time. It’s both block-by-block local and galactic in scope, atomically familiar and extraterrestrial.

But the soundtrack’s emotional weight is inextricable from the thematic gravity of “Black Panther.” In the film’s dueling rivalry between T’Challa and Killmonger, it’s easy to see the internecine conflict within Lamar: the unstinting desire to make the world better, but the need to hermetically preserve a sense of self. Despite the nature of his fame, Lamar is notoriously private, eschewing social media and rarely mentioning his personal life. He’s acquiesced to some of the expectations of a pop star by appearing on Taylor Swift and Maroon 5 singles, but regularly invokes his Compton roots in both his music and financial contributions to the community.

[The film’s themes] reminded me of why I made ‘To Pimp a Butterfly.’ It was survivor’s guilt.

— Kendrick Lamar

“[The film’s themes] reminded me of why I made ‘To Pimp a Butterfly,’” Lamar says. “It was survivor’s guilt. You want to be homegrown and help folks back home and give them game. You want to be there for them but if you’re there, then you can’t go out and explore.”

As he famously said, “I don’t do it for the ’Gram, I do it for Compton.” And its residents will surely be among the millions watching Lamar during awards season as he makes the leap from perpetual Grammy darling to a Golden Globes and Oscar favorite. The good kid from the M.A.A.D city taking center stage, supplying volume for the voiceless, speaking for far more than just his friends, family and his agent.

“I don’t know what I’ll say if I win,” Lamar says. “A lot of different emotions will be running through me, and I usually just say what I’m inspired to say at that moment … what comes off the chest. It’s just a great thing to know that these bodies of work come from a simple thought and you put that simple thought down on wax, and then you give it to the people and it goes from there.”

FULL COVERAGE: Get the latest on awards season from The Envelope »

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.