They can write, they can act, but can they direct? Turns out, these Hollywood talents can

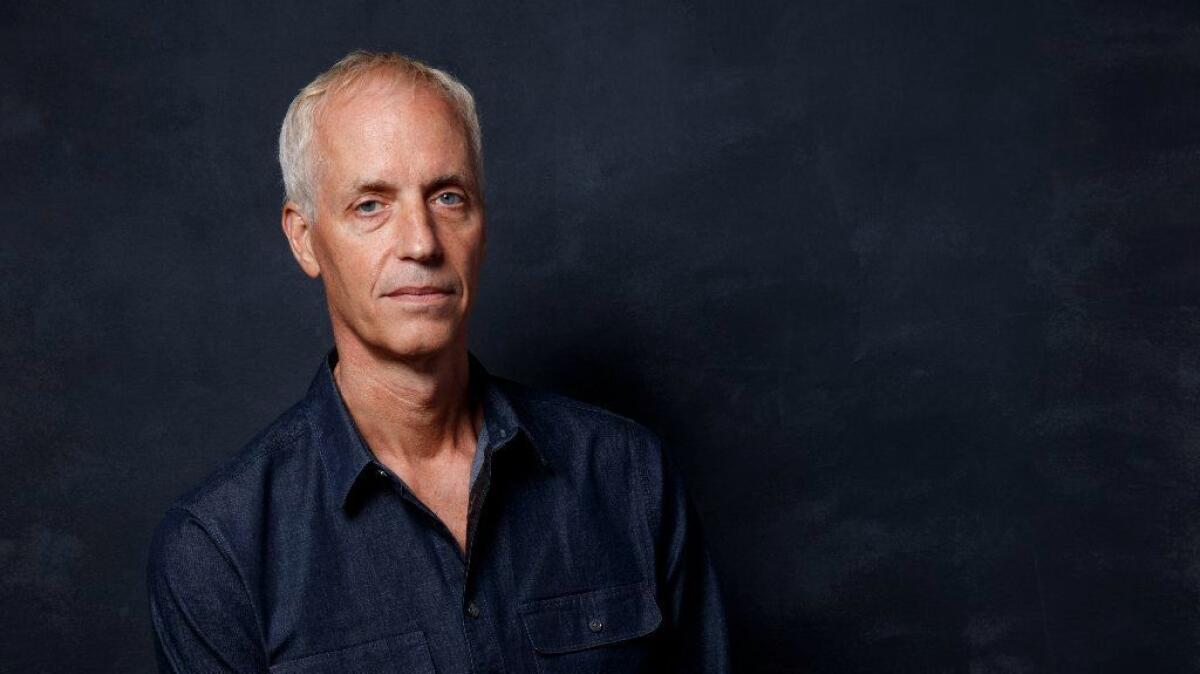

“It’s not true that I always wanted to direct,” says Aaron Sorkin, who audiences know best for his balletic verbosity in such screenplays as “A Few Good Men” and “The Social Network,” and from the TV series “The West Wing.” “I’ve never felt that screenwriting was a stepping stone to another job – it was the job I wanted.”

Yet Sorkin is now a debut helmer with “Molly’s Game” -- a Christmas release starring Jessica Chastain and featuring Idris Elba and Kevin Costner -- despite his admission: “I can’t pick a long lens out of a police lineup. Jumping into the deep end of a big pool is true on a lot of levels.”

Making that leap into the virtual unknown didn’t stop Sorkin or other Hollywood vets best known for expertise in other areas of filmmaking. This year, writers-turned-first-time-directors include Danny Strong (“Rebel in the Rye”), Marti Noxon (“To the Bone”) and Sorkin. Actors too are changing chairs. Greta Gerwig made her directorial debut with “Lady Bird,” Jordan Peele with “Get Out,” Andy Serkis with “Breathe” and actor Kumail Nanjiani wrote and starred in “The Big Sick.”

For some, this has been a long-planned move. Strong says he wanted to direct once he watched his first screenplay, “Recount,” being produced in 2008. “It turned it from a ‘one day I’ll do this’ to an actual goal,” he says. I saw [director] Jay Roach up close making decisions and realized I wanted to be in charge of the company.”

Serkis’ first turn as a director is the upcoming “Jungle Book,” but it’s his second film, “Breathe,” that hit theaters last month. For him, wanting to direct “goes all the way back to before even becoming an actor,” he says, when he studied visual arts in college and then got bit by the acting bug. Spending years working on Peter Jackson’s “Lord of the Rings” and “Hobbit” films was an “extraordinary film education,” he says.

See the most read stories this hour »

Being an actor, says Serkis, gave him a leg up in understanding just how to approach both scenes and actors alike. “Actors can make great directors,” says Serkis. “They know what it’s like not to be prescribed to. As a director, it’s your prerogative to shift the performance to shape the narrative and tone, but the skill is to do that without in any way fettering what the actors want to do.”

For Nanjiani, sculpting those scenes on the page was made easier thanks to his acting experiences. “As an actor you’re always breaking down the emotional journey, or arc of the scene, and how it affects the cast or relationship to the character,” he says.

He was also prepared by producer Judd Apatow for all the rewrites that would be necessary to get a script that would work: “Each rewrite, even if we got just a little bit better, we knew we were heading in the right direction.”

Intriguingly, most of the filmmakers making their transitions did so while being relatively unconcerned that their technical knowledge might be lacking. Most had experience watching from the sets of films (Sorkin says he’s “not done working with great directors” like David Fincher; Strong had Lee Daniels pulling a few strings at Fox to get him practice directing “Empire” episodes).

And they didn’t flinch at the idea of learning either on the job or after the job, as Dan Gilroy notes. Gilroy’s second film, “Roman J. Israel, Esq.” is just entering the awards season conversation, but his 2014 “Nightcrawler” led him to spend the in-between years “really educating myself; I studied lenses and digital versus film for two to three years.”

Noxon, on the other hand, hesitated before directing her own script. Like Sorkin, she’d been a showrunner on TV series like “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” and “Private Practice,” but says, “There’s a real machismo in the film business that’s not conscious – but they tell you in every way possible way that you’re not able to direct. That you’re not smart enough, or you don’t know cameras, and as a woman raised in a certain era I certainly bought into that.”

Fortunately, she notes, “The miraculous thing was discovering with ‘To the Bone’ that I didn’t have to know everything, and just had to surround myself with people who knew more than I did, and we’d help each other.”

Which is ultimately what every director has to do, whether it’s a first or a 40th film – since, after all, a director’s education never wraps.

“I know I still need to learn everything,” says Strong. “It’s endless. I feel like I went to grad school and got a PhD making the film. You really are thrown into the deep end – and it’s just an incredible learning experience.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.