Varying a film’s structure keeps it one step ahead of sophisticated audiences

While penning an early draft of “Manchester by the Sea,” writer-director Kenneth Lonergan got bored.

“I’d probably gotten maybe two-thirds of the way through and I was bored to death and I knew something was wrong,” the Oscar nominee recalls. “When things are working well, the structure of a film and the content follow the same lines, and you know you’re in pretty good shape. But I was so bored I knew I had to do something different.”

A rethink of how to tell his story — about a man who refuses guardianship of his teenage nephew after his beloved brother dies — led to the version the film academy awarded with six Oscar nominations, including an original screenplay nod. It’s a story that’s part family tragedy, part mystery. And the reason it holds a coil of suspense about the man is that the rewrite held back the reveal of an even greater tragedy in his life until more than midway through.

Lonergan isn’t the only filmmaker to ignore straight narrative this awards season. Directors and screenwriters with such films as “Moonlight” and “Nocturnal Animals” dared audiences to follow along with nontraditional or twisted storytelling — hoping that makes them more intriguing.

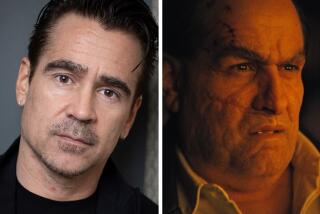

Amy Adams, Jake Gyllenhaal, Michael Shannon, Armie Hammer and Aaron Taylor-Johnson star in Tom Ford’s “Nocturnal Animals.”

In the case of Tom Ford’s “Nocturnal Animals,” the story switches back and forth between a fictional horror tale and the real-life effects the novel has on the characters. In addition, star Jake Gyllenhaal plays both the book’s hero and the ex-husband of the reader (Amy Adams).

“The pieces are interwoven and one cannot live without the other,” notes Ford, who adapted the structure from the book by Austin Wright on which the film was based. “The inner novel and her flashbacks start to drive each other, and eventually all three worlds are fueling each other. We as an audience need to know that the inner story has something to do with the outer world, which makes us wonder what is in that story.”

Sometimes it’s not about burying a mystery, though; in the case of eight-time Oscar nominee (including adapted screenplay) “Moonlight,” dividing the film into three specific chapters (and changing the actor playing the lead character as he ages) was director and screenwriter Barry Jenkins’ choice. The source material, a shelved play by Tarell Alvin McCraney, was more of a “day in the life” story that jumped around in the timeline.

“He decided it was a stronger presentation of the story to organize it that way, to allow you to be with one character fully,” says producer Adele Romanski. “In reorganizing that literature he did add some story line and work that wasn’t in the source material — but he wanted to choose key defining moments about this character’s identity. These are the critical formative experiences he wanted to share.”

It’s a form of artfulness to tell a nonlinear story, and artfulness is one of the elements that can attract voter attention during awards season. But filmmakers seem to be more aware that modern audiences can handle more sophisticated storytelling and they want to rise to the occasion.

In some ways, Lonergan is already a step ahead: He tries to leave bread crumbs that will lull viewers into going off course just a bit. “People are ultra-sensitive if they’re sitting down to watch stories,” he says. “Things in movies are over-explained [to audiences] so much these days it’s like they think they’re morons. It’s difficult to stay ahead of the audience. Occasionally you have to make artificial adjustments because people have expectations.”

One of my favorite tricks is to layer in things that have nothing to do with the story, to beef up the sense of it being like real life.”

— Kenneth Lonergan

So what does he do? “One of my favorite tricks is to layer in things that have nothing to do with the story, to beef up the sense of it being like real life,” he says.

Ultimately, an unusual structuring of a movie shouldn’t be just for show or to trick viewers. In his first film, “Sleepwalk With Me,” screenwriter-director Mike Birbiglia (who recently released “Don’t Think Twice”) often broke the fourth wall to speak directly to the audience, as in one of his stand-up routines.

As he notes, “The reason for a story to exist is crucial. The amount of effort that goes into a film is often literally years of effort — so you sure as hell better have a reason to tell the story. Structure can alter that story. So you have to always wonder: ‘Is this story worth telling?’ And then understand how it should best unfold.”

See the most read stories this hour »

ALSO:

2017 Oscars Buzzmeter: Critics predict who will win in the major categories

Before ‘Moonlight’ was an Oscar-nominated movie, it started as a play we never got to see

Academy rules that ‘Moonlight’ and ‘Loving’ are not original screenplays, but adapted

Tom Ford crafts a layered thriller-within-a-thriller with ‘Nocturnal Animals’

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.