How Native Americans in the arts are preserving tradition in a changing world

“It’s a good day to be indigenous!” said KREZ radio’s scrappy DJ Randy Peone, played by the late great John Trudell in the 1998 film “Smoke Signals.” And just like that, Indian country inherited a sunny new motto, replacing the previous one, which was about, well, dying: “It’s a good day to die!” The film was celebrated — on and off the rez — for its insights into contemporary Indian country. The Los Angeles Times even noted that realism in a review, saying that when the film cited “historic injustices or contemporary issues in Native American culture, it does so with wry, glancing humor.”

For non-Native audiences, it was a glimpse into Indian country that they hadn’t seen before, something far different from how the “Indian experience” had historically been portrayed. It was a landmark moment in contemporary cinema: American Indians had become real people, lifted out of a frozen, mythological past into the world as modern, living communities. As we close the month officially designated as Native American Heritage Month, a time when the U.S. engages in national conversations about American Indians, our very existence is a reminder that for us, the conversation never ends.

If there is such a thing as the modern “Indian experience,” celebrated Cahuilla and Cupeño novelist and essayist Gordon Johnson writes the Native California version of it. With his roots on the Pala reservation in northern San Diego County, the titles of his books “Fast Cars and Frybread: Reports From the Rez” and “Bird Songs Don’t Lie: Writings From the Rez,” his recently released work from California publisher Heyday Books, make it abundantly clear he relates most closely to Indian country. But his writing also draws non-Native people in with appeals to what he calls the “universality of the human condition.”

“Writing is a real lonely pursuit; you’re on your own so much, but you do want to have a connection with humanity,” he says. “I write hoping I send stuff out there and maybe someone connects with me [and] I’m connecting with people.”

It’s easy to see Johnson as the reclusive writer that he frequently describes himself as. His rez house is filled with an eclectic mix of handmade Indian art and an electric guitar collection scattered on the walls. Out back through the scrubby desert yard is his writing studio, a stuccoed hay-bale structure that insulates against the blistering Pala summers. Above the door hangs a 1960s-era Bing Copeland longboard, one of Johnson’s prized possessions from his surfing days, and on the desk sits an IBM electric typewriter.

Johnson is an old-school writer, working for years as a columnist with the Press-Enterprise in Riverside.

I have kids and 11 grandkids, and I’d like to leave a little legacy for them, so when I’m gone, there will be a whiff of me left on the planet.

— Gordon Johnson

While he writes for Native people, Johnson says he “writes for story,” and he hopes readers feel a little more alive when they’ve read him. “One of the frequent comments I get from people is they say, ‘When I read your stuff, I feel like I’m home.’”

At the same time, he’s aware of the differences between Native and non-Native audiences. “I shouldn’t say this,” he chuckles, “but non-Native people don’t know if you’re [lying to] them, but with Native people you have to be on the mark or they’ll know it!”

As a Native writer, Johnson says he doesn’t write only to sell books; instead he’s more interested in reflecting what it’s like to be a California Indian today, blending modernity with ancient indigenous continuity into a seamless, culturally based whole of everyday life.

“Also,” he says, “I have kids and 11 grandkids, and I’d like to leave a little legacy for them, so when I’m gone, there will be a whiff of me left on the planet.”

Johnson’s experience mirrors what many Native artists and writers experience daily: that need to balance life within the dominant society, their inherently political identities as citizens of tribal nations, and making a living. Native writers such as Johnson are faced with the ever-present challenges of representation and authenticity, but indigenous artists, photographers and fashion designers face similar obstacles, and perennial questions: Who is it that Native people create art for? And why?

Ambassadors of culture

Despite the career viability of art, there is nothing easy about being an Indian artist.

In Native societies, art was integrated into the act of making everyday things and art objects were often ceremonial; Native people frequently note that the word “art” is virtually unknown in indigenous languages. Today, making a living as an artist is mediated by market forces with demands of its own. At stake are complex dynamics that weave together identity and culture with non-Native expectations about value based on authenticity. This inevitably involves stubborn stereotypes born from lack of knowledge. It also means that the Native artist, no matter the genre or medium, wittingly or unwittingly is cast in the role of educator.

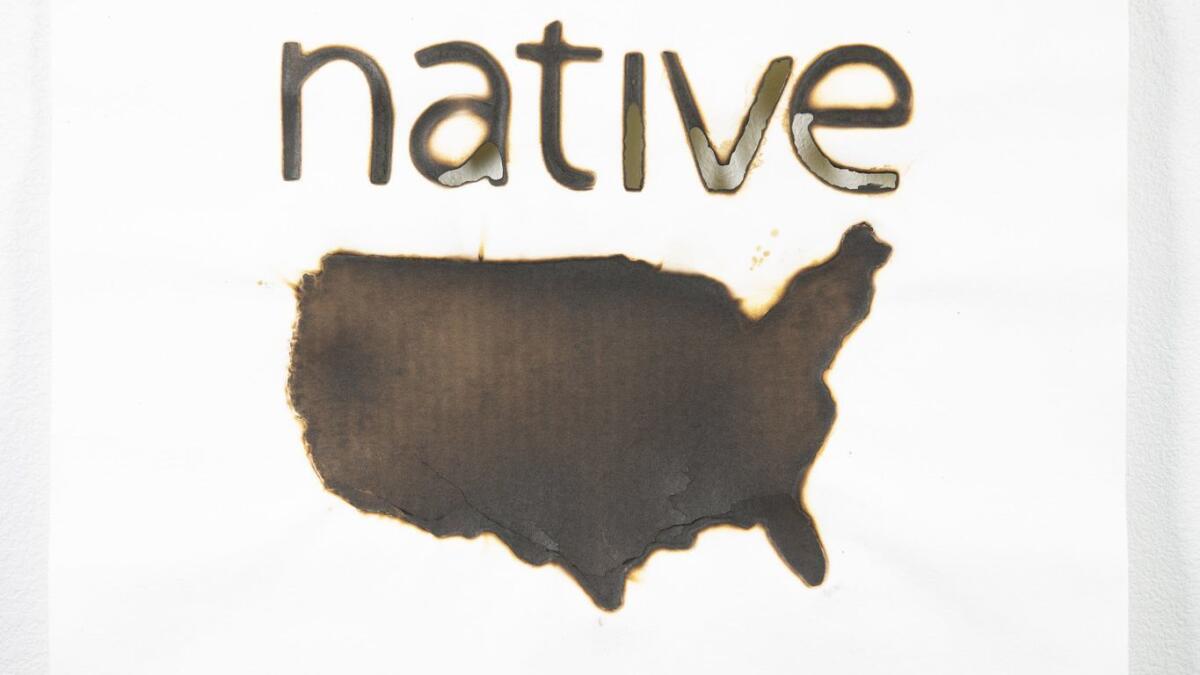

“I fell into a trap for 10 years or more of trying to educate the non-Native about what Natives were about,” says Gerald Clarke Jr., a Cahuilla artist known for his large welded sculptures. “It’s a trap because the default setting for mainstream America is that the artist is the ambassador of the community, and that almost replaces the interest in the artist’s own creativity.”

Clarke, also a professor of ethnic studies at UC Riverside, infuses his Cahuilla identity into painted works and sculptures, which he creates often from found objects and garbage. His massive 6-foot basket made from crushed beer and soda cans has been widely exhibited, including at the Autry Museum and the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Pamela Peters, an L.A.-based Navajo photographer and filmmaker, on the other hand, embraces the educator role. Her photographs of Native people deliberately work against the well-worn stereotypes of what she calls the “relic Indian” — the buckskin, beads and feathers Indian. In her series titled “Real Ndnz Retake Hollywood,” for instance, Native people appear in black and white head shots evocative of the glamorous 1940s era Hollywood.

“I’m motivated because of everything happening to our communities,” Peters says. “We’re dealing with racism, and that’s why we have a lot of kids committing suicide, because they see this racism and hatred from television, sports, from people mocking us on different platforms in media. Or people questioning if we even exist, like asking us: What degree of Indian are you?”

An inevitable aspect of educating non-Native society is disrupting the concept of authenticity; that is, what is considered “authentic” Indian art. Clarke points out that the creation of the Indian art market was based on the authenticity of the Indian artist. Even the Indian Arts and Crafts Act — which is a truth-in-advertising-law that mandates Native people are able to prove their tribal identity — is really designed to benefit non-Native people more than artists.

“The mainstream wants to commodify the object and have it as part of the overall art market, but they don’t really want to know what we think,” Clarke says. “ Who decides what’s authentic? Is it the academic, the art historian, or is it the community?”

Commodified arts

In 1998 when “Smoke Signals” was made, it had been five centuries of a relentless genocidal onslaught and a long succession of egregious federal policies that left Indian country in a state of grinding, crushing poverty. But capitalism waits for no one, least of all Indian country, and for them, it was join or die.

U.S. colonialism had long intended for Indians to disappear into a cash economy. Survival necessitated economic self-sufficiency, and the exploitation of Native art traditions was targeted as part of federal assimilation policy.

In the 1870s, Brig. Gen. Richard Henry Pratt was a proponent of “Americanizing” indigenous communities and started government boarding schools that mandated cultural assimilation. He also provided art supplies to Kiowa, Comanche, Cheyenne and Arapaho prisoners of war at Ft. Marion in Florida. Their artworks, ledger drawings, were a form of historical documentation in many Plains tribal nations, often referred to as “wintercounts.” Images painted onto buffalo and other animal hides depicted important events in the life of the community and was later adapted to paper ledger records kept by traders and military.

Who decides what’s authentic? Is it the academic, the art historian, or is it the community?

— Gerald Clarke Jr

Pratt also incubated a plan to commodify ledger drawings. While imprisoned, ledger artists Zotom (Kiowa) and Howling Wolf (Southern Cheyenne) were connected, for example, by Pratt to wealthy white art patrons like Eva Scott Fényes (who was one of the original supporters of Los Angeles’ first museum, the Southwest Museum of the American Indian created by eccentric polymath Charles Lummis), commissioning them to create drawings for her. It was a calculated tactic to incorporate them into the U.S. market economy and was refined under the 1887 Dawes Act, which codified the official and brutal policy of forced assimilation.

By the early 20th century the Fred Harvey Detours were bringing trainloads of tourists to Santa Fe’s burgeoning Indian art scene. The Southwest Indian Fair and Industrial Arts Exhibition had its inaugural show in 1922 as a way to foster and preserve Indian art forms while creating economic opportunity for Native people. It also worked to ensure the value of Indian art in advance of a market wave of tourist trinkets and souvenirs. After undergoing numerous changes over the years and reorganizing into today’s Southwest Assn. for Indian Arts in 1959, the Indian Fair evolved into today’s Santa Fe Indian Market which is still considered the most prestigious Indian art show in the world.

Since then the arts, all kinds, have been a viable career option for Native people.

Unlike the non-Native art world, however, the Indian art world has never upheld any meaningful distinctions between fine art and craft. An exceptionally crafted basket or piece of beadwork is accorded the same respect as a fine painting or sculpture. In addition to painters and sculptors, some of the most famous Native artists have been jewelers, basket makers, beaders and potters. San Ildefonso Pueblo, N.M., potter Maria Martinez (1887-1980), for instance, became world famous for her black-on-black Pueblo style pots as a result of the Indian Fair and her legacy lives today, passed down through her descendants and other students.

The Southwest Native art world was never limited to Southwest people but drew from tribal nations all over the country.

The influence of these artists can be seen in some of today’s well-known painters, such as Benjamin Harjo Jr. (Absentee Shawnee-Seminole) and Eric Tippeconnic (Comanche). Harjo’s abstract, Pop-art style has earned him a reputation as one of the Indian art world’s most valued artists. Tippeconic, whose imagery conjures ancient Plains life as easily as it brings the past into visual conversation with the present, refers to himself as a “historical artist.”

“I often use my art as a means to generate historical dialogue or at the very least as a method to induce a conversation that will inevitably end up as a discussion related to history (most often Native American History),” Tippeconnic said via email. A history professor at Cal State Fullerton, Tippeconic uses art as a platform to teach the subject. But he uses his art to also draw attention to Native culture in its many manifestations, such as a series he painted based on the Apache Sunrise Ceremony, or other current issues of Native life.

Wrestling with authenticity

One of the goals of the Santa Fe Indian Fair in its project to build an Indian art market was to ensure the authenticity of Indian art, and that has been a hallmark of the Indian art world ever since, for better or worse. It’s a double-edged sword. It can set up impossible standards for Native people to live up to, yet it simultaneously works to filter out cultural appropriation and ethnic frauds. Still, collectors and Native artists alike take it seriously, relying on tried and true markers of tribal tradition often contained in the practice of storytelling.

Crow and Northern Cheyenne fashion designer Bethany Yellowtail calls herself a “storyteller in fashion,” invoking a bedrock cultural custom that is always framed by values rooted in a distinctly indigenous worldview. At the same time, she is concerned about respecting tradition in her fashion and accessory business which is a collective of Native artists.

We want to support and amplify our communities, so how do you find the balance as a global market brand and maintain integrity as a Native person?

— Bethany Yellowtail

Reflecting on what it means to respect tradition, Yellowtail says, “We want to support and amplify our communities, so how do you find the balance as a global market brand and maintain integrity as a Native person?”

The B.Yellowtail collection brings Bethany’s original fashion designs together with one-of-a-kind handmade jewelry pieces, beadwork, moccasins, and more, imparting a sense of cultural genuineness and assurances that the work has been properly vetted.

“I’ve decided that it’s clearly about sticking to our core community values like reciprocity, in how we support our other artists and our collaborations,” she says. “We have certain protocols about things; I’m very mindful about what can and can’t be used.”

Respecting traditional protocols is part of the complexity of balancing market concerns against authenticity, however one defines “authentic.” This is about representation, which is always fraught terrain in Indian country, especially when it comes to film.

The film industry is notorious for both perpetuating Native stereotypes (think of the ubiquitous “relic Indian”) and ignoring Native Americans as modern people in vibrant communities. And, as actor, producer, and director Kimberly Norris Guerrero (Colville/Salish Kootenai/Cherokee) says, the industry is fickle in its demand for Native actors:

“As an actor, my biggest challenge is the very thing that has kept me working all these years — the double-edged sword of being a Native American actor,” Guerrero said in an email. “On one hand, you get the calls when the roles come around. But when those roles dry up, as they have for the past few years especially for Native women over 40, I don’t work. For some reason, I’m just not thought of when it comes to playing a judge or a mom or an FBI agent. Fortunately, the theater community is more ambitious in its casting.”

Guerrero is best known for her role in the television sitcom “Seinfeld” as Jerry’s Native American girlfriend, where the show exploited her ethnicity to push back against stereotypes through humor. With her unmistakably indigenous look, in the vast majority of her film and stage work she has been cast as Native characters, including the iconic Cherokee tribal chairwoman Wilma Mankiller in “Cherokee Word for Water” (2014). Playing the lead role in a film about a modern Native cultural hero — especially a woman — is still an all too rare phenomenon in Hollywood.

Controlling how Native people are represented in television and film is how they can best work to reverse all the worst patterns. “Smoke Signals,” the first all-Indian produced major motion picture in history, was the signature movie that has led to the creation of a Native film industry, and a proliferation of Native film festivals in the U.S. and Canada. Joely Proudfit (Luiseño/Payomkowishum), executive director of California’s American Indian and Indigenous Film Festival, views her role as crucial to changing the way American Indians are seen in media:

“I do not consider myself an artist in the traditional sense but a Native woman, mother, educator, and media maker who tries to elevate the representation of American Indians in mass media,” says Dr. Proudfit, who has also taught American Indian studies for over twenty years.

“As a PhD in political science, I quickly learned that if I wanted to change policy or more effectively influence social, economic and political change, I could be more effective in striving to change our narrative through art and media,” Proudfit says. “Working with Native media makers, directors, producers, writers, performers and artists, I help to provide resources to film and television industries, mass media and independent content creators that improve understanding and foster authentic representation of Native American and indigenous peoples in storylines, exhibition and marketing campaigns”

Art as cultural sovereignty

Proudfit’s views point to the inseparability of authenticity, representation and the broad political terrain of Native sovereignty in all realms of indigenous existence, including the arts. If the creation of an Indian art marketplace was originally intended to assimilate Native people into the dominant society through capitalism, how do Native artists view the dominant society’s assimilative impulse in an era of tribal self-determination?

Gordon Johnson, ordinarily not one given to sweeping political statements, nonetheless sees Native art as a matter of sovereignty.

“I can’t speak for everyone,” he says. “I’m a simple guy, but I think Native art is an expression of cultural sovereignty, which, in the biggest picture, is the ability of Native people to determine who they are. And it begs the question: What is Native art? I think it is an exploration of cultural identity.”

Things are far from ideal in Indian country. Racism and violence are only some of the problems Native people continue to face. But it’s also undeniable that we’ve come a long way since the days of Pratt’s prisoner of war art projects and the Fred Harvey Detours, now a century in the past. We may still have a lot of work to do to heal the wounds inflicted by colonialism, but in the long run, KREZ DJ Randy Peone was right: It really is a good day to be indigenous.

Dina Gilio-Whitaker (Colville Confederated Tribes) is a writer and educator in indigenous studies.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.