How ‘brown buffalo’ Oscar Acosta, best known as Hunter Thompson’s Dr. Gonzo, inspired his own TV doc

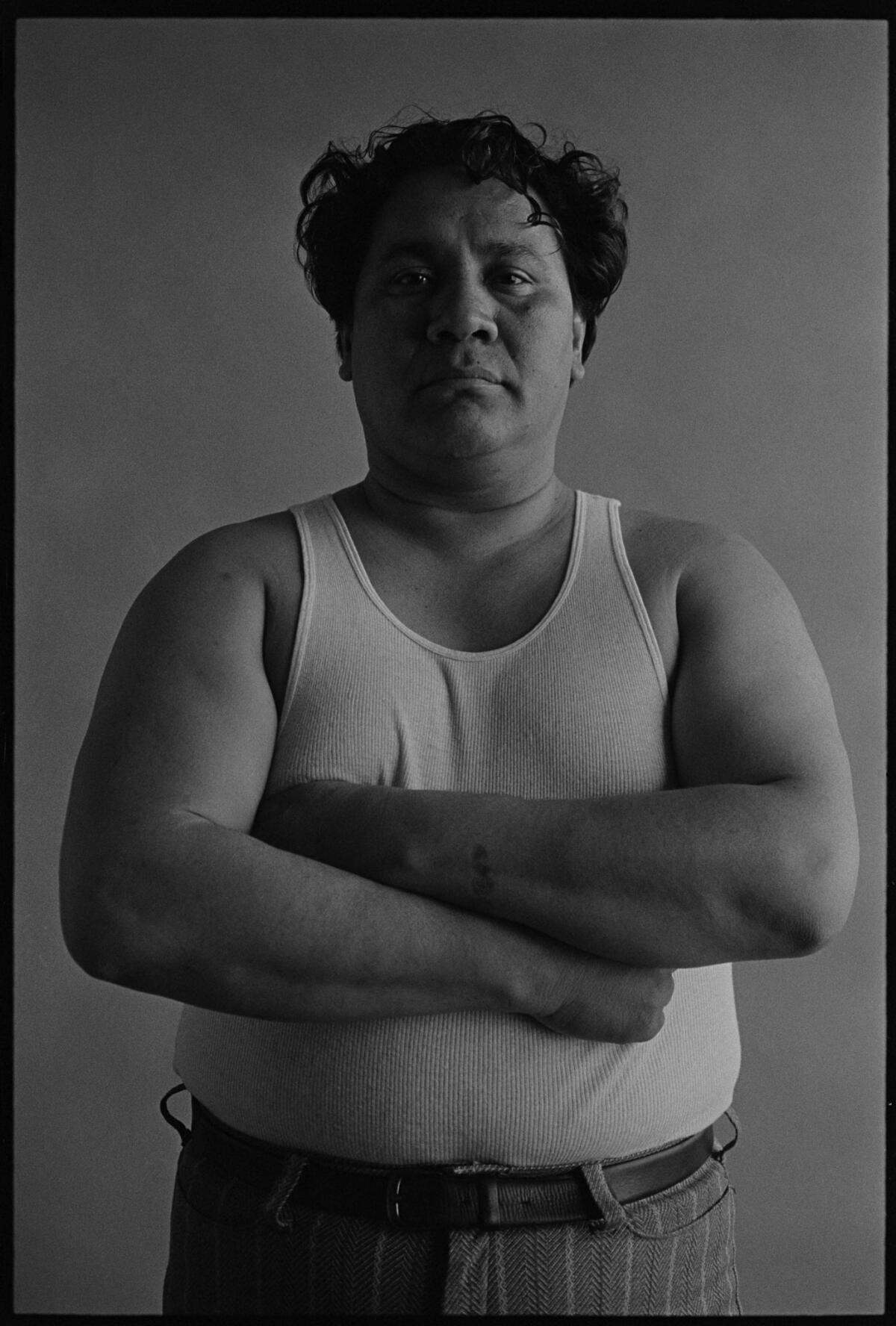

There was his size: a substantial 6 feet, 225 pounds, according to his FBI file.

There was his style: a Chicano attorney who materialized in Los Angeles courtrooms in loud ties, bearing business cards embossed with the Aztec god of war and, on at least one occasion, a gun.

Then there was his death, which was not so much a death as a disappearance, somewhere in the vicinity of Mazatlán, Mexico, in 1974.

Oscar “Zeta” Acosta was not only large, he was larger than life. The son of a peach picker, he was an activist lawyer who helped defend the “Eastside 13,” the 13 men indicted by a grand jury for their role in planning the East L.A. school walkouts of 1968.

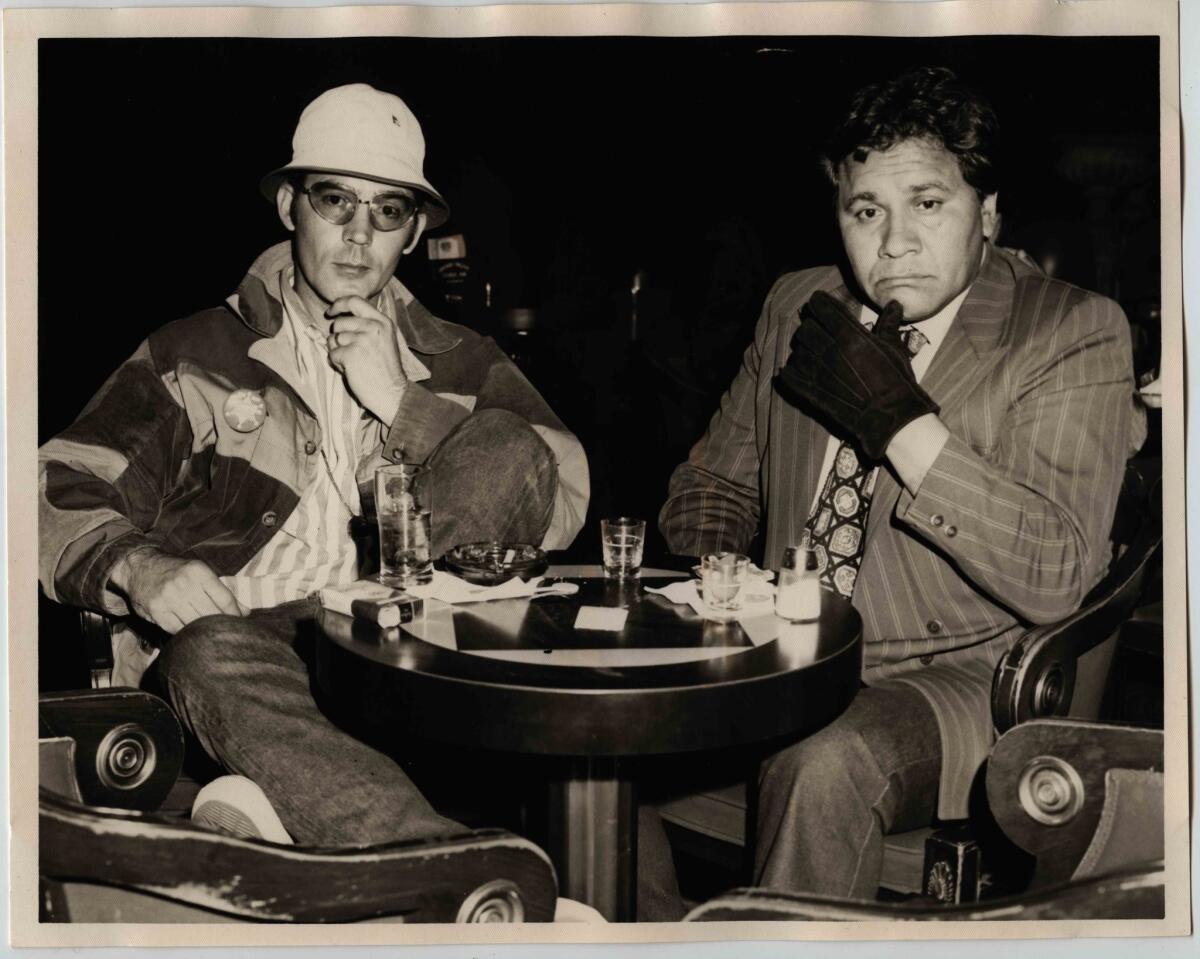

But his place as one of pop culture’s most indelible characters came via his pal Hunter S. Thompson, who used Acosta as the inspiration for “Dr. Gonzo” in the drug-fueled roman à clef “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.”

Acosta also wrote his own hallucinatory, semi-autobiographical books — “The Autobiography of the Brown Buffalo” and “The Revolt of the Cockroach People.” The books, like their author, elude classification: not-quite-novels, not-quite-memoirs that offer keen observations on race, masculinity and the mind (Acosta was likely bipolar) amid a series of wild episodes that touch on his gargantuan appetite for adventure, food and women — not to mention, narcotics.

“There isn’t much sense in trying to explain what a ‘bad trip’ is,” he writes in “Brown Buffalo.” “You simply lose your marbles. You go crazy. There is no bottom, no top. The devil sits on your head and warns you of your commitment.”

Acosta, who liked to refer to himself as a “Brown Buffalo” — in a nod to the “fat brown shaggy snorting American animal, slaughtered almost to extinction” — is now the subject of a new documentary set to air on PBS Friday night.

“The Rise and Fall of the Brown Buffalo” is the first film to tackle the life of the polymath who burned fast and bright and whose writerly tendencies have prevented his ideas from disappearing into nothing, in the same way as his body. It’s directed by Phillip Rodriguez, who has made films about Pancho Villa, artist Manuel Ocampo, comedian George Lopez and Ruben Salazar, the Los Angeles Times and KMEX journalist who was killed in East L.A. while covering the 1970 Chicano Moratorium antiwar protest.

Why did he turn to Acosta? For one thing, Rodriguez says, “He was an untimely man that society, that psychiatry, that race awareness simply wasn’t prepared for.”

“He’s this contradictory, difficult, charismatic pain in the ass,” the director adds. One whose complexes and privileges echo the conditions of many young Chicanos today.

“He resembles young raza infinitely more than other [civil rights] icons,” says Rodriguez. “Oscar was entitled. Oscar was impatient. Oscar felt that his time was now. Oscar had gone to law school. He was fed up and capable of confrontation.”

Likewise, his books weren’t simply restless narratives of drunken episodes and floundering sexual encounters. In poetic and prescient ways, Acosta articulated the in-between-ness of Chicano identity.

“I hate for people to assume I’m an authority on Mexicans,” Acosta wrote in “The Autobiography.” “Just because I’m a brown buffalo doesn’t mean I’m the son of Moctezuma.”

Erick Huerta, a spoken word artist and activist from Boyle Heights, who helped present a special screening of the documentary at La Plaza de Cultura y Artes in downtown Los Angeles last week, says Acosta’s story remains relevant.

“It’s a brown man going through an existential identity crisis,” he says. “He’s not from here, he’s not from there. All of these differences, all of this dichotomy — you have to figure out your own truth and walk your own way.”

And that way doesn’t overlook the unseemly.

“Nowadays, everyone talks about the movement and the moratorium and the activism,” says Huerta. “But nobody talks about getting crazy high and throwing Molotov cocktails — but that happened too.”

Rodriguez discovered Acosta through office gossip.

When he was a child, his father, who was also an attorney, would share stories about a lawyer known for his courtroom antics.

“He would tell me about this Mexican guy, a lawyer, wearing a guayabera and insisting to the judge that it was appropriate for the courtroom,” he recalls. “One time, he showed up in the courtroom barefoot. My father probably had begrudging respect for him but also probably a little disgust. My parents were pursuing the politics of respectability, of middle class decency. Oscar eschewed that completely.”

But it wasn’t the lore that stoked Rodriguez’s interests in Acosta. It was his books.

“It heartened me to read this complicated tribute to himself,” Rodriguez says. “To his cylindrical brown beauty, to his incapacity to fit the white male ideals of this culture.”

“Autobiography of a Brown Buffalo” opens with a poignant scene in which Acosta stands in front of a mirror and examines his naked, corpulent body.

“Every morning of my life, I have seen that brown belly from every angle,” he begins. “I was always a fat kid. I suck it in and expand an enormous chest and two large hunks of brown tit.”

Acosta forces the reader to gaze upon his body: its brownness, its bulkiness, its frailties (he was plagued by bleeding ulcers) — and what it meant to inhabit such a skin in a country in which brown has never been the ideal.

You don’t have to be perfect to dissent....You can be flawed. You can be fat. You can be funny. You can be drunk...and still be effective.

— Director Phillip Rodriguez on Oscar Acosta

It’s a condition that Rodriguez, the grandson of Mexican agricultural workers, identifies with.

“He’s like me,” he says. “He’s like my uncles, my brothers. There is a lot of humor and rage and entitlement and capacity, and it’s in this place where you have to go and bottle it.”

When Rodriguez graduated from UCLA film school in the 1980s, he dreamed of turning Acosta’s delirious life into a feature film. “But in corporate showbiz, to get funding you need a bankable star,” says Rodriguez. “And where is the fat Mexican that is also a bankable star?”

When the opportunity arose to do a documentary, however, Rodriguez says he jumped.

But even the documentary has been no easy task.

Acosta left behind a trove of writings: There are his two books, an archive of letters and stories maintained by his son, Marco Acosta, as well as an extensive written correspondence with Thompson — who was both carousing partner and frenemy. (Acosta maintained that various ideas in “Fear and Loathing” originated from him and threatened to sue Thompson’s publishing company, Straight Arrow Books, prior to the 1973 release. Straight Arrow placated him with a two-book deal — part of the reason “The Autobiography” and “Cockroach People” exist as published works.)

It’s a brown man going through an existential identity crisis. He’s not from here, he’s not from there.

— Spoken word artist Erick Huerta on Oscar Acosta's story

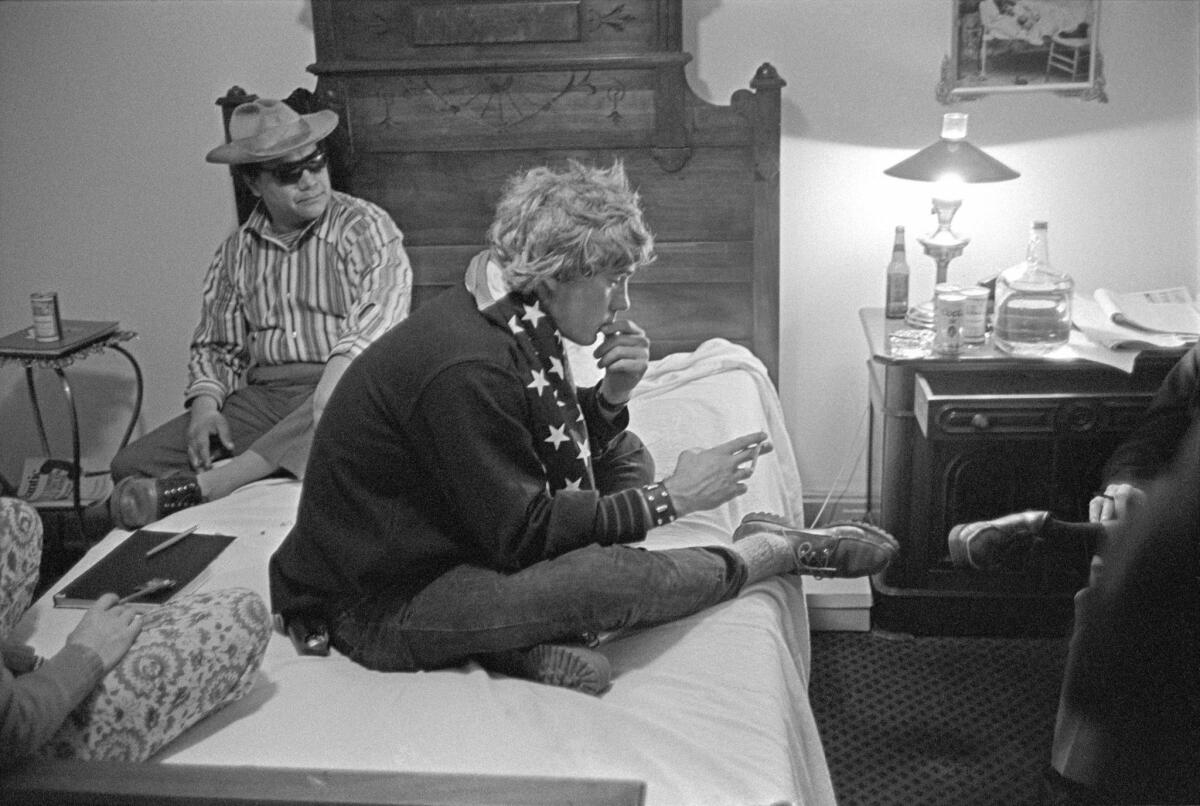

But there is very little of Acosta on film, which left the filmmaker without much to work with when it came to moving images. So Rodriguez decided to scrap the traditional documentary format — filmed images punctuated by talking heads — for something more experimental: dramatizations of Acosta’s life inspired by the author’s written works and interviews with family, friends and colleagues.

Playing Acosta is Jesse Celedon, who embraces the messiness of Acosta’s person and life. Jeff Harms plays the boozy Thompson. There is even a cameo by former L.A. Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, who can be spotted as a concerned judge.

The more flexible format allows for the introduction of fantastical visual elements, which better evoke Acosta’s life.

“You’d kill Oscar if you put him a Ken Burns-like container,” says Rodriguez. “He’s about this drug-fueled, ego-driven way of telling a story. We are trying to be true to that.”

“Rise and Fall of the Brown Buffalo” travels chronologically through Acosta’s life: his birth to a working-class Mexican family in El Paso in 1935 and his formative years in the tiny town of Riverbank, Calif., outside Modesto, where he would begin to grapple with racial lines.

“In my corner of the world there were only three kinds of people: Mexicans, Okies and Americans,” he wrote. “We had an unspoken rule that you never fought one of your own kind in front of the others. In the battle for group survival, you simply don’t weaken your defenses by getting involved in family squabbles in front of the real enemy.”

Acosta completed his university studies in the Bay Area then went on to receive his law degree from San Francisco Law School. For a time, he worked for the East Oakland Legal Aid Society. But his restlessness led him to abandon the job and, during a period of wandering, he ended up in Vail, Colo., where he befriended Thompson.

By 1968, he had landed in East L.A., where he devoted his legal abilities to helping the Chicano cause.

“I took no case unless it was a Chicano case,” Acosta’s stand-in says in the documentary. “And turned it into a platform to espouse the Chicano point of view.”

In his actions, he was outrageous: He once subpoenaed every member of the L.A. County grand jury as a way of proving discrimination against Mexicans. He ran a losing campaign for L.A. County sheriff on the promise that he would shut down the sheriff’s department. His political activities led the FBI to begin keeping a dossier.

“He was so dissonant,” Rodriguez says. “He was not all peace and love. And his relationship with other activists was very complicated. Off the record, many of them spoke disparagingly of him.”

Just as he abandoned his job as a legal aid lawyer in Oakland, Acosta ultimately abandoned legal activism for writing. Then he abandoned the U.S. for Mexico — where, in 1974, he was last seen, reportedly moving a boatload of marijuana near the Mazatlán coast.

But his books have kept him alive — urgent stream-of-consciousness missives that weren’t bound by the more baroque conventions of Latin American literature.

“A lot of Latino literature suffers from trying to fit into a mold,” says Ilan Stavans, an Amherst College humanities professor, who is also the author of “Bandido: The Death and Resurrection of Oscar ‘Zeta’ Acosta.” “But he is his own mold.”

“He is very much in the spirit of Jack Kerouac, of Hunter Thompson,” he adds. “Not writing but typing. That’s what [Truman] Capote said of Kerouac: He didn’t write, he typed. It’s unprocessed. It’s unfiltered. It comes as a force from within him. It’s almost being vomited on the page.”

But if Acosta channels Kerouac or Thompson in his style, in his ideas, he is resolutely his own man — his search for self delved into the complexities of race and indigenist themes.

“They stole our land and made us half-slaves,” Acosta writes in a particularly lyrical passage in “The Autobiography.” “They destroyed our gods and made us bow down to a dead man who’s been strung up for 2000 years … Now what we need is, first to give ourselves a new name. We need a new identity. A name and a language all our own.”

Ultimately, it is his profound humanity, full of weakness and insecurity, that makes him such a compelling subject to scrutinize on the page and on film.

“He shows us you don’t have to be perfect to dissent,” says Rodriguez. “You can have human desires. You can be flawed. You can be fat. You can be funny. You can be drunk. You can be randy and still be effective.”

“The Rise and Fall of the Brown Buffalo”

Where: KOCE

When: 9 p.m. Friday

Rating: TV-14

MORE

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.