Q&A: Artist-run space 356 Mission is leaving Boyle Heights. Founders Laura Owens and Wendy Yao explain why

After five years of operating out of an old piano warehouse on the outskirts of Boyle Heights, 356 Mission, the artist-run space founded by Los Angeles painter Laura Owens and Wendy Yao, founder of the art bookstore Ooga Booga, will come to a close in May, after shows by painter Alake Shilling and installation artist Charlemagne Palestine come down.

“It was a labor of love, with finite resources, and never intended to last forever,” read a written statement released to The Times on Thursday afternoon. “We still believe that art spaces are vital to the cultural empowerment of all people, and that artists can be allies of vulnerable communities.”

The closing comes in the wake of a steady stream of anti-gentrification protests that have seized headlines since 2015, when a growing number of art spaces began to establish commercial storefronts in the industrial area that hugs Mission Road, just across the river from the Arts District. 356 Mission, on at least two occasions, was the target of protests from activist coalitions such as Defend Boyle Heights.

Last year, staff at the gallery met with protesters who demanded that art galleries leave Boyle Heights. Owens declined to do so, responding via a statement on the gallery’s website: “Alongside the protesters’ demands to close, we have also heard the voices of artists, community groups, families, and individuals in the area who want 356 to remain open.”

Owens and Yao say their decision to now close has more to do with the natural life cycle of an artist-run space coming to an end than any protests.

“It was just time,” says Yao.

356 Mission began as Owens’ studio in 2012, where the artist produced a series of large-scale paintings that she then put on view in the space. That 2013 exhibition led to other exhibitions and events. In a subsequent performance, for example, artist Joe Sola and Michael Webster fed one of Owens’ massive paintings into a wood chipper.

“That was amazing,” says Owens with a laugh.

After five years of doing what we wanted to do, we felt that for personal and practical reasons ... this is the right moment to close.

— Laura Owens, founder, 356 Mission

Over time, 356 Mission grew from an informal studio and gathering spot into a more established artist-run space with a staff of eight. Over five years, they have staged more than 300 events and more than 50 exhibitions — featuring emerging unknowns as well as established figures such as Gary Indiana and appropriation artist Sturtevant in her last U.S. show before her death.

In this lightly edited conversation, Owens and Yao discuss what led them to close the space, the tug-of-war between art and gentrification and the unusual nature of the 356 Mission program.

What were the circumstances that led you to shut down 356 Mission?

Owens: Our lease was ending and we felt it was the right time. After five years of doing what we wanted to do, we felt that for personal and practical reasons that we had had a great experience and this is the right moment to close. The lease ends at the end of June. We will be closing in May.

Did the anti-gentrification protests spur the decision?

Owens: If it was for that, we could have closed a long time ago. Wendy and I have talked about this so many times. If you’re in the neighborhood, you make an effort to engage.

Yao: I felt that there was more that we could do there than not being there. While we don’t agree with the demands of the protesters, we really were trying to show up. But we have a lot of reasons for why we are leaving. It had sort of run its course. Doing the space was always a labor of love and was always really hard on both of us. And the protests added to this weight.

Owens: For Wendy and I, it was like our third jobs. I teach at Art Center. I’m an artist. Wendy has a store in Chinatown [which will remain open]. She also has other jobs. So we would go there and do this after.

What will happen to the space after you move?

Owens: We talked to the landlord and we recommended ideas for a nonprofit. But we have no control over it. The landlord [Vera Campbell] is sensitive to the issues of the neighborhood. But she owns the building and she can do whatever she wants. I really don’t think it’s up to us to say what would be appropriate there.

What led you to establish 356 Mission to begin with?

Owens: It’s something I’d done in Los Angeles for many years. I’d had shows in my studio. I’d organized shows at the Eagle Rock cultural center in the early ’90s. [For the first shows at 356 Mission] we had the space and while my paintings were up, we invited people to do performances. Wendy and I got excited about saying yes to artists’ ideas.

Yao: I’ve been operating my bookstore in Chinatown for a long time and I’ve been organizing free public programming in different ways for more than 20 years. Laura found this space and invited me to be a part of it. And it made it possible for me to continue the kinds of programs I’ve always been doing, but in ways that couldn’t exist within the limitations of my store, which is like 325 square feet.

How did 356 Mission sustain itself financially?

Owens: We were not a nonprofit. We had different ideas at different times for how it could sustain itself. We thought we could sell art from some of the shows and sometimes that happened. We did get a grant for the last show we did, but that was really only one time.

Mainly I would sell a painting and my gallery, [the New York-based Gavin Brown], was helping by donating money from art I was selling. We did an art fair that helped fund this. If someone put their heart into something, then getting them some money for the work they made was a positive thing. But that wasn’t the motivation.

Yao: And there was never a motivation for us to take home the proceeds. We reinvested everything back in the space.

Owens: We operated at a loss the whole time.

How much of a loss?

Owens: That’s not something I would like to think about.

How did exhibitions at the space evolve over time?

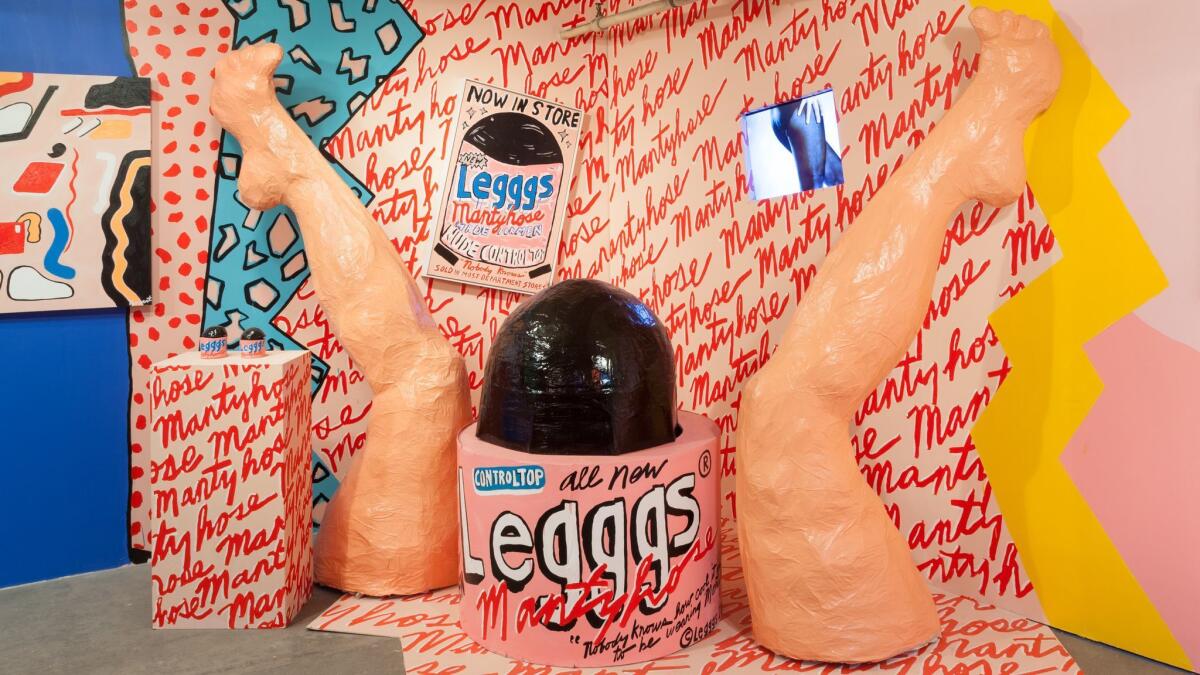

Yao: Things just unfolded. We worked with a musician I’ve known since the ‘90s, Seth Bogart. He’s been making these short films and papier-mache sculptures. We loved what he was doing and invited him to do a show. But the way the exhibition would unfold, it included music performance and a lip sync festival.

When Kerry Tribe did an exhibition [that explored aphasia, a condition that affects the way the brain processes language], there was a panel talk on aphasia with people from an aphasia group.

Owens: I really liked being behind the scenes and seeing what artists we could invite. Gary Indiana came and made art. Eric Wesley came. Watching their thinking process as they created their shows was eye-opening.

We were trying to challenge the gallery model. We’d have things up for three months, for one month, we’d let someone live in the space and make work. We’d try to follow a writer or performer’s ideas, not say ‘no’ as much as possible.

At what point did the anti-gentrification protests begin and what did you do to address them?

Yao: That was early last year.

Owens: It had started before. [One of our staff members] had been to a community meeting. We had been reaching out to them to talk about ways we could work together. Then the Hammer [Museum’s] Artist Council, which consists of Andrea Fraser, Charles Gaines and myself, had a meeting. It was about how can artists get involved and better organized and be better activists. So there was a meeting and they protested that meeting. We only had that particular protest and then another one — so just two.

Anyhow, we kept trying to meet with them and we did meet with them. But I discussed most of this in the statement I made [last year].

Developers will often do things like establish art competitions and artist residencies as a way of promoting real estate interests. How do you contend with the ways in which art is used as a tool for development?

Yao: This conflict has raised a lot of important questions and self-reflection about the role that art can play. At the end of the day, we feel we have more in common with the protesters than not. Artists can be instrumentalized by a real estate developer — but I think that’s why artists should work with protesters. To make sure that artists and galleries don’t fall into that. We are against displacement, but we don’t feel that galleries closing their doors will solve those problems.

Owens: We have been talking about this — about what art gets into a gallery and what does a white wall represent. It’s a difficult issue, but it’s an important one for artists and galleries not to be unwittingly used. But there were artists who attended events and they proposed events to us before, and then they turned around and said, “We’re not going there.”

Do you see a resolution between the galleries and the protesters in Boyle Heights?

Owens: That’s what we asked [the protesters]. We had a long list of ideas for common ground. And it is something that galleries need to do, to work with local communities and make sure they are supportive of local economies and communities.

Yao: We did that in a lot of different ways. On a very basic level, we had lists in our space of local businesses that we patronized: if we had to go to the hardware store, if we needed to buy food. If visitors came, we’d share that list so that we could be participating in the local economy. People on staff reached out to neighboring residences and schools to invite them to participate in events. We had weekly programs and workshops. We were constantly re-examining. It was about being good neighbors.

Owens: When there was a concern about increased police surveillance because of the galleries, we were proactively against police surveillance. We wrote to the Hollenbeck captain and asked them to end the hate crimes investigation. And we asked them to refrain from intervening in protests in our space.

But ultimately we really believe in art and music and performance and books and all of these things. This is a place where people can meet each other, where they can experience something that is reaffirming.

What of 356 Mission will remain with you after it closes?

Owens: I am just awed by how many different ways people use their body and their mind to create something inventive and unique. We really did have such a wide range of artists — from the very, very young vegan cookbook writer to a 90-year-old artist. I always felt enlightened. I was given many gifts through their words and their bodies and their art.

Yao: I grew up sitting on the floors of bookstores and record stores. Those spaces were a big part of my growth as a human. My bookstore is not a library, but it’s still a free place to hang out. You don’t have to buy anything. People can come to exchange ideas and learn. Looking back at this experience, holding space for community, it’s intense, it’s inspiring, it’s rewarding and it’s also really heartbreaking and hard. But all I can say is I’m extremely grateful to have been a part of this.

+++

Alake Shilling, “Monsoon Lagoon,” and Charlemagne Palestine’s “CCORNUUOORPHANOSSCCOPIAEEAANORPHANSSHHORNOFFPLENTYYY”

Where: 356 S. Mission Road, Boyle Heights, Los Angeles

When: Shilling’s exhibition is on view through April 29; Palestine is on view through April 22

Info: 356mission.com

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

ALSO

A Dream Displaced: In L.A.’s first suburb, a feeling of unease in the age of Trump

An arts nonprofit closes shop after 'constant attacks' by anti-gentrification activists

As rents soar in L.A., even Boyle Heights' mariachis sing the blues

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.