We watch artist Harry Gamboa Jr. stage a fotonovela at the site of L.A.’s demolished 6th Street Bridge

The performance begins with coffee. Artist Harry Gamboa Jr. is distributing cold brews, flat whites, pour-overs and espresso to a dapper crew of roughly two dozen performers — clad in everything from business suits to green lipstick — who have all materialized at 2 p.m. at the Blue Bottle Coffee shop in the Los Angeles Arts District on a Saturday in early December.

The occasion: Gamboa is orchestrating one of his fotonovelas, part of an ongoing project in which he stages impromptu human tableaux in urban settings, then captures the scene with photography.

For more than a year, he has been focused on a fotonovela series titled “The Sixth Expanse,” centered around the demolition of the 6th Street Bridge, the viaduct that once connected downtown Los Angeles with the Mexican American neighborhood of Boyle Heights.

“So many things happened on that bridge,” says Gamboa, who as a young man, lived in Boyle Heights. “When I heard, I thought about how meaningful the bridge had been to me.”

Which is why he finds himself in the Arts District on a wintry afternoon, gathering with his performers — a loose troupe of friends and colleagues known as Virtual Verité — over coffee at Blue Bottle, which lies just steps from the foot of the old bridge.

It’s not every day you see artists making art in the ever-gentrifying Arts District.

“I get everyone feeling really good,” says Gamboa, who is dressed in a stylish black suit accented by a tie marked with red. “Then we work on the shoot.”

For the artist, the fotonovelas are part of a long-running practice of staging surreal scenes and then photographing them. Gamboa was a founding member of the art collective Asco in the early 1970s, which was known for creating invented film stills (called “no movies”) and faux news photography (such as the iconic “Decoy Gang War Victim,” from 1974, which purports to show a victim of gang violence).

His fotonovelas go back to the 1980s, when Gamboa began experimenting with sequential series of images featuring performers in extreme and dance-like poses — often in ways that respond to facets of urban design and architecture. The Spanish name fotonovelas is a nod to photonovels, or photo comics, which employ photos instead of illustrations, and were especially popular in Europe and Latin America during the 1950s and ’60s. (As a boy, Gamboa was an avid reader of comics.)

The artist’s fotonovelas have appeared in myriad formats — as projections, in zines and in art catalogs and literary journals. For a time, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, he would publish them on his website, then remove them.

“I was playing around with the idea of creating material for the Internet and then taking it away,” he explains, “to invalidate the footnotes.”

What happens when the place you make your mark has been removed?

— Harry Gamboa Jr., artist

Before there is any fotonovela, however, there is always a gathering.

Blue Bottle echoes with the laughter and conversation of Gamboa’s collaborators, who are decked out in dark suits, fine dresses, wild eyeshadow and at least one red blazer with tinsel trim — the latter worn by artist Chris Velasco, channeling a be-wigged, holiday-loving character he has dubbed “Barry.”

“If we can freak out the hipsters,” he laughs, “then I know I’ve done my job.”

For Gamboa, simply bringing everyone together is part of the piece. In this buoyant mix are friends, fellow artists and art world colleagues — such as El Nopal Press founder Francesco Siqueiros — as well as a number of current and former students. (Gamboa teaches at Cal State Northridge and the California Institute of the Arts.)

“It has this ephemeral quality to it,” he says, “making any space in Los Angeles where we meet the coolest place to be.”

It also has the effect of connecting art world professionals with neophytes, master’s candidates from the graduate fine arts program at CalArts with first-year students from Northridge — most of them Chicano, like Gamboa.

“He creates a community and then has a performance,” says Jazmin Urrea, an interdisciplinary artist who is working on her MFA at CalArts. “And that performance creates a community.”

At 2:40 p.m., once everyone has been adequately caffeinated, Gamboa leads a procession of performers out of the cafe to an area at the foot of the old 6th Street Bridge, which has been barricaded.

“The bridge is completely gone,” Gamboa says. “This used to be the start of the bridge.”

He has been shooting around the bridge since demolition began in January, tracking its slow disappearance in a series of fotonovelas. His December shoot is the last to employ the bridge — or, more accurately, its absence — as its subject.

For the artist, this is bittersweet: The 6th Street Bridge has a personal significance. Gamboa recalls the day, as a young boy, that his father took him and his two brothers for a meal at Clifton’s.

“We walked from Boyle Heights to downtown,” he recalls. “One of my brothers got really tired on the way back and had to be carried. It was a big trek. But it was pretty great. It was about perseverance — and it showed me how easy it was to cross that bridge.”

Gamboa isn’t the only one who has poignant memories.

Entertainment 2016: Year in Review »

“I was born in Mexico, in San Luis Rio Colorado,” says Benjamin Quiñones, a writer who grew up in Boyle Heights, and makes regular appearances in Gamboa’s fotonovelas. “My mom had family in Boyle Heights, so we moved here. We took the Greyhound bus, and my uncle picked us up in a blue Impala. I was 4 years old.

“To get to Boyle Heights, we had to go over the bridge. And I remember looking out over the bridge, and I was like, ‘What is this world?’ ”

“To cross that expanse was more than crossing the bridge,” Gamboa says. “It meant that you were delving into a different cultural realm.”

As the Virtual Verité performers assemble at Mateo and 6th streets, Gamboa gets to work putting them in poses — all before a chain-link construction fence with a sign that reads: “This Property Closed to the Public.”

Some individuals, he places in gestures of defiance. Others take more reticent stances. Puzzled-looking urban professionals in workout wear stop to admire the scene — then pull out their cellphones to document it. It’s not every day you see artists making art in the ever-gentrifying Arts District.

“No one move,” shouts Gamboa — and gets to work shooting, first with one of two still cameras, then with video. The photography takes about 15 minutes, requiring everyone to hold their poses while the artist dashes back and forth, taking a combination of wide shots and close-ups.

Gamboa wraps up his final shot. “Thank you, everybody,” he exclaims, and the group relaxes.

Elements from this shoot will ultimately end up in the European publication Pfeil, as well as the L.A. art magazine Artillery. The artist has done almost 20 shoots related to the bridge — in Boyle Heights, downtown and all along its expanse.

“Bridges are, on some level, rather mythical,” he says. “But it doesn’t take a physical bridge to traverse space.”

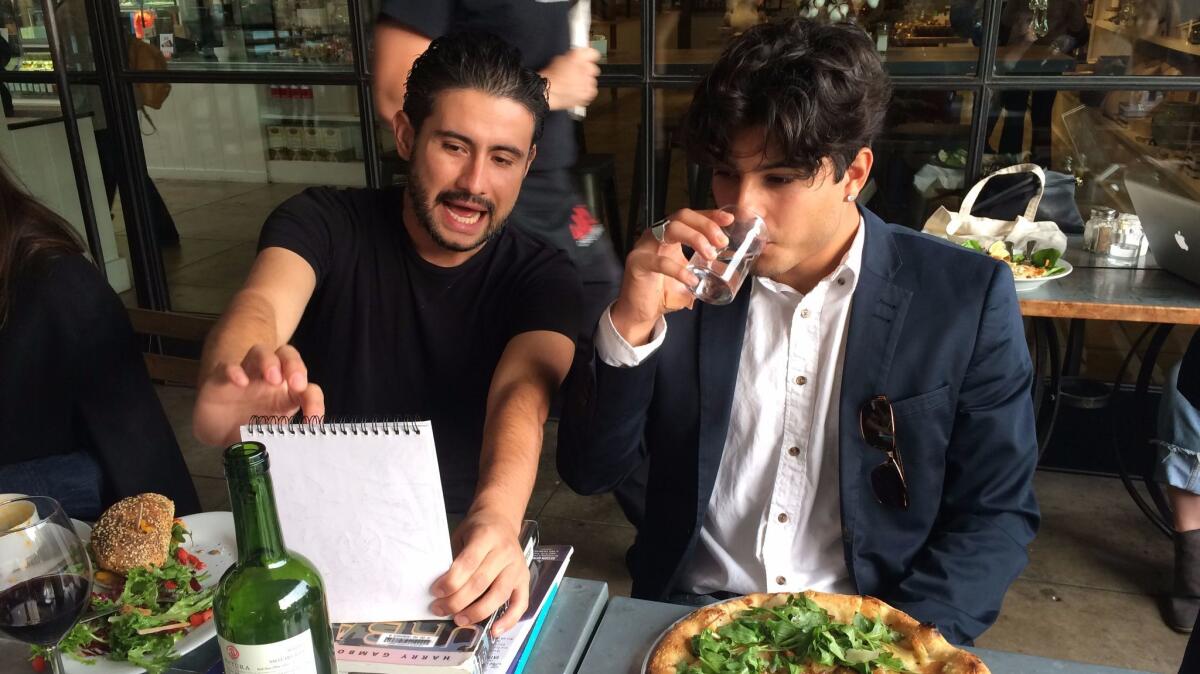

With the shoot wrapped up, Gamboa leads his procession of performers to a restaurant on Mateo Street, for a collective lunch on his dime.

“The social part is what it’s about,” he says. “There is a crossbreeding of ideas. Many of the people here are gifted photographers, painters, sculptors and a handful of theorists.”

“And some rabble-rousers,” adds Quiñones with a laugh, as he settles into a long outdoor tables.

Gamboa says he chooses his collaborators carefully. “No divas,” he says with a wry smile. “I want everyone to pull together, help each other out.”

Pizzas and pastas begin to arrive, and the group chatter travels loosely from photography to literature to issues of gentrification.

“The Sixth Expanse” is a unique record of a piece of civic architecture that is no more.

“I have images of the bridge in various stages of disaster,” Gamboa says. “There was one point where I photographed these pillars that looked like Greek columns. And the next day, they were gone. It’s part of what I talk about when I talk about Los Angeles. Many things function like a mirage.

“This work itself is about ephemeral actions,” he adds. “It’s all temporary. We are temporary. In the end, we make our mark — but what happens when the place you make your mark has been removed?”

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

Find me on Twitter @cmonstah.

ALSO

Painter Jonas Wood turns Arata Isozaki’s MOCA exterior into building-sized art canvas

‘It hasn’t left me’: How Black Lives Matter used performance to create unforgettable 2016 moments

Art after Fidel: What Castro’s death means for a rising generation of Cuban artists

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.