Q&A: As Gronk’s set designs go on view at CAFAM, the artist talks opera, painting and B-movie crab monsters

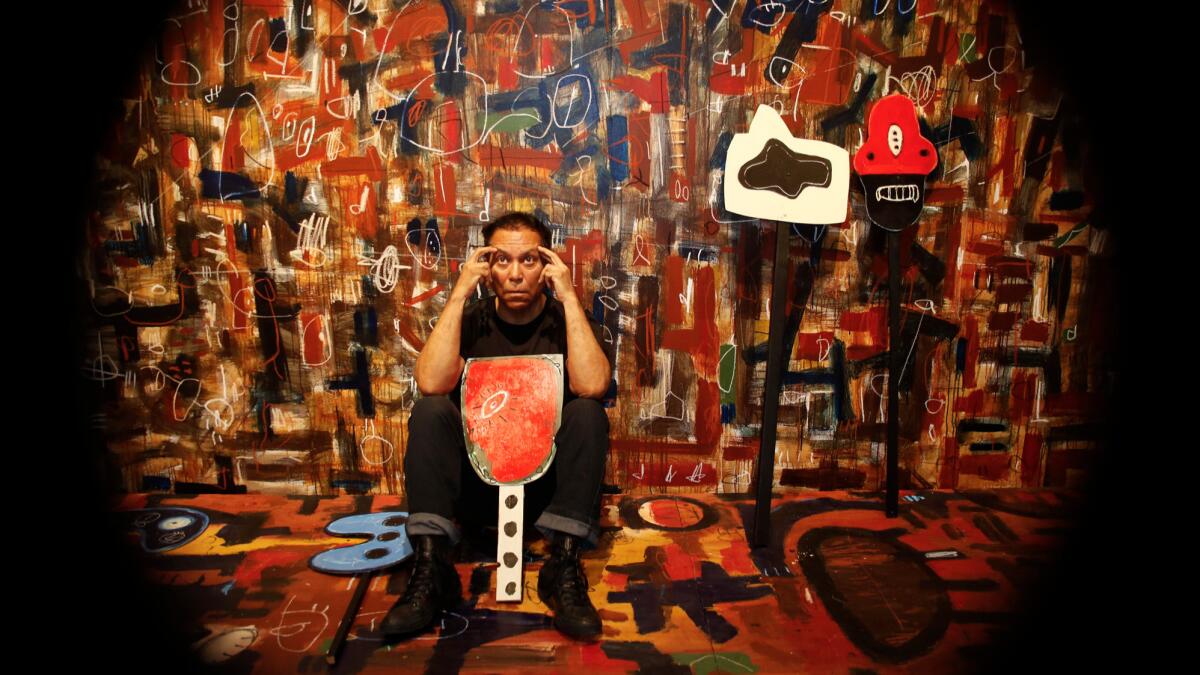

Gronk is an artist who has never been stuck on a single style of art-making. The Los Angeles native — born Glugio Nicandro — has always had a voracious interest in many types of art.

He has taken photographs, exchanged mail art and staged wild performances in the streets of Los Angeles, most famously, with the collective Asco, which he helped found in the early 1970s. A longtime painter, he has a large-scale canvas on view in the exhibition “Don’t Look Back” at the Museum of Contemporary Art.

Through it all, Gronk has also been an accomplished set designer — producing pieces for small, experimental plays staged in neighborhood cultural centers, as well as internationally touring productions helmed by award-winning director Peter Sellars.

A new exhibition at the Craft & Folk Art Museum (CAFAM) in Los Angeles brings together the gamut of Gronk’s theatrical work: early backdrops, hand-painted masks, illustrations and documentation, as well as a new set built with the purpose of allowing invited guests and viewers to take the stage themselves.

“If someone wants to come and read their poetry, they can do that,” he says. “We’ll have readings and there will be different groups of people who come in and do performances.”

“Theater of Paint,” as the show is called, also nods to the artist’s long-running fascination with another theatrical genre: B-movie science fiction — in particular “The Giant Claw,” a low-budget flick from 1957 about a giant bird-creature hell-bent on planetary destruction. (Sample line: “You keep your shirt on and I’ll go get my pants on.”)

Gronk took time out from installing the show to talk about his career as a set designer. In this lightly edited conversation, he discusses how he got into set design, the worst play ever written, and why “The Giant Claw” should be revered as high art.

What’s it like seeing a career’s worth of set pieces come together for this show?

Sometimes you cringe because you see things that for were not at the apex of your output. So for example, there’s a big piece from the first play I ever did — which I like to call “The Worst Play Ever Written.” It’s not one of my favorite pieces. But it was important to show historical context.

Initially, when I first started, I felt like I was painting for the audience member who was sitting all the way in the back. But then I tried to think of the sets as objects that would hold up on their own outside of the opera. And in working with Peter [Sellars], I began to think of them as pieces that you would be able to examine up close — that they would hold up as paintings. That transformation is part of what this show is about.

How did you first get into set design?

It goes back to the days with Asco, where we did performance-type pieces. The earliest play I did — a real sit-down performance — was by a Polish playwright [Slawomir Mrozek] who wrote a play called “Striptease.” I starred in the play too. It was held at the Hispanic Cultural Center and we staged another performance at Otis [College of Art and Design].

It was about two people tossed into a room. They don’t know who tossed them and there are these two big hands that force them to strip off their clothes. It’s Poland, so the hands are a symbol for the Russians. And the two people represent the left and right. They can’t fight the hand because they don’t unite. Finally the hand shows up and crushes them.

I created the whole set out of paper. The play called for a minimalist white room, but I didn’t think that way at that particular moment in time. I had white sheets of paper that were torn and crumpled, paper was scattered all over the floor. It was kind of a garish-looking set. That to me was the beginning of recognizing that the audience would be looking at the set as much as the actors on it.

What was your first big commission?

Oh, that was “The Worst Play Ever Written.” That’s how I like to describe it. They know who they are! [Laughs.] It was at L.A. Theatre Center probably sometime around 1989.

It had something called a “Garden of Sorrows.” And they wanted a hospital and a pyramid and all of these different things. It also had a big disc because there was supposed to be a total eclipse onstage. And there’s this woman and she’s walking very slow. And there’s this man, and he’s walking very slow. And he lands on a rock and covers himself with the fabric and he becomes the rock. And the woman, there are sticks under her skirt and she becomes a tree.

It was unbelievably bad. But, hey, I was doing Polish plays with giant hands and Theatre of the Absurd. When I read it, I thought, how will they get away with this? It was so ridiculous, I thought maybe I can contribute, so I said yes. [Laughs.]

You’ve collaborated regularly with theater and opera director Peter Sellars. How did you two first connect?

I had seen [his opera] “Nixon in China” at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion and it was one of those events where half the audience booed and the other half clapped. I thought, “If our generation has produced anything of value, this is it.”

I was doing a play at the Mark Taper and someone came to the design room and said, “Peter Sellars is rehearsing ‘The Persians,’ do you want to see it?’” And I go and I see this man introducing everyone on the stage: “This is the handler. This is the guy who brings our lunch. This is the costume designer. And this is Gordon Davidson, the director of the Mark Taper Forum.” And Davidson says, “I don’t need any introduction.” And I’m laughing way in the back and [Peter] says, “Who are you?” And I’m like, “I’m Gronk.”

After that, I saw him in Madison, Wis. He was doing a play and I was doing print-making. He said, “Let’s talk because I want to work together.” I ended up working with him on Jean Genet’s “The Screens.” That’s how it started.

What did you do for that play?

I created maybe 14 to 15 screens for the production — all paintings on canvas. [The show at CAFAM has] one of the original ones that is being shown and it’s kind of an image of a moon and a washing machine. They’re both about cycles: The moon cycle and the endless dry cycle. Peter often brought his work into present-day situations.

The play was staged in Boyle Heights initially, in a warehouse probably sometime in ’95 or ’96. The audience had to lift their chairs and move wherever the painting was moving. The lighting designer had designed these backpacks with light that followed the paintings around.

It was a body of work where the audience is close up to the painting. Often sets are very flat because lighting designers like the flatness. But this had to be different. I layered the paint, so when it was illuminated, you’d see color upon color upon color.

You and Sellars recently collaborated on “The Indian Queen,” a Henry Purcell opera about the Spanish conquest of the Americas, which has toured Europe and Russia. This opera seems designed for Southern California: an L.A. director, an L.A. set designer and a story about the Conquest in a place that used to be Mexico. Any chance it might be shown here?

I wish it would be shown here. I think the only place to stage it would be the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, but I don’t think they have an interest in it. “The Indian Queen” is lengthy. It’s challenging for an opera-goer. It is not “La Bohème.” It is not “Madama Butterfly.” It is something else. When Peter asks me to do something, I always say yes because we’re creating things that are art and that are challenging to listeners and viewers.

‘The Indian Queen’ is lengthy. It’s challenging for an opera-goer. It is not ‘La Bohème.’ It is not ‘Madama Butterfly.’ It is something else.

— Gronk

This opera, in a way, is all about L.A. It’s all about our times. It’s all about the things we see every single day. It would be idyllic for it to come here but I don’t know if there are any U.S. places that would do it.

Your show at the Craft & Folk Art Museum also touches on your love of film. What kinds of cinematic references can we expect?

It’s this show that crosses over from classical music to opera but it also has a B-movie sensibility, which I have a fondness for. I love the fact that I can create these operatic sets but also abide by things you can find in a B-movie.

It’s the fact that it’s made cheaply. I like the desperation of no money and making something. During the Asco time, we had no money. We had no facilities. So what do we do? We make a “No-Movie.” We stage a scene but we don’t film it.

So things like strings in a movie are important to me. Wiring is important to me. A nail hanging out of a painting is important. It’s those defects that make it art. There is a person behind those creatures in “Attack of the Crab Monsters.”

I have an homage to “The Giant Claw” in the show. These are the types of films that get discarded, but they’re important to me. In this show I give “The Giant Claw” the red-carpet treatment it never got when it came out! [Laughs.]

You’ve said in the past that the color palettes you’ve seen in the movies have influenced your painting practice. How so?

I think of “War of the Worlds” — the 1953 version— and Vincente Minnelli and the musicals Hollywood was pumping out. For me the beauty of it was the saturation of color. It was red reds, blue blues and there was no mincing it. That influenced my earliest paintings. I took from that information and did not dilute the color in any way. I wanted the red to read red.

Then my palette came down considerably and I started explore a dark film-noir quality in my work. Then I went to more earth tones. I think of the bear movie that won the Oscar...

“The Revenant”?

Yes, “The Revenant.” Happy bear trails!

You’ll be screening some of your favorite films as part of the show. What do you have in mind?

“The Curse of the Doll People,” from Mexico, early ‘60s. And I’ll have “The Giant Claw,” of course, which is my “Citizen Kane.” And there is “Ship of Monsters,” also from Mexico. That’s one where a woman has this glittery pipe cleaner on her shoulder and right away it indicates that she is from outer space. She has to be from outer space!

I like the desperation of no money and making something.

— Gronk

That’s what I love about these movies. It’s that cheapness. It’s that imagination. They’re using a certain language and I have fondness for that. And I compare it to [Rene] Magritte writing, “This is not a pipe” [on a painting]. In this case, “It’s not a pipe cleaner.” It’s from outer space!

You’ve watched a lot of cheesy sci-fi over your lifetime. What’s the craziest flick you’ve ever seen?

There is this film called “The Creeping Terror,” from 1964. It’s this shag rag from outer space that swallows people up and at one point it attacks a hootenanny. The people are attacking it with their guitars, but it gobbles them up. It makes the “The Giant Claw” look like “King Lear.”

Where: Craft & Folk Art Museum, 5814 Wilshire Blvd., Mid-Wilshire, Los Angeles,

When: Runs through Sept. 4.

Info: cafam.org

ALSO

28 outdoor paintings go up for RFK Mural Festival, turning L.A. campus into alfresco art gallery

The theater of Trump: What Shakespeare can teach us about the Donald

From ancient Persian poetry rises ‘Feathers of Fire,’ billed as largest shadow-theater play

How Southern California became the backdrop to an opera about a ‘hysterical’ woman

Find me on Twitter @cmonstah. Find Gronk on Instagram @elgronk.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.