Ceramic artist Dora De Larios on shaping her own path by melding the Mexican, Japanese and Modern

Editor’s note: Dora De Larios died at age 84 on Jan. 28, one day after this piece was published. Find the Times obituary here.

Just about every corner of Dora De Larios’ home appears to be inhabited by a magical being. A whimsical feline figure peeks out from a dining room cabinet. Wide-eyed owls etched onto tin observe the kitchen from cabinet doors. In one corner of the living room, a helmeted figure from an indeterminate era sits atop a regal horse.

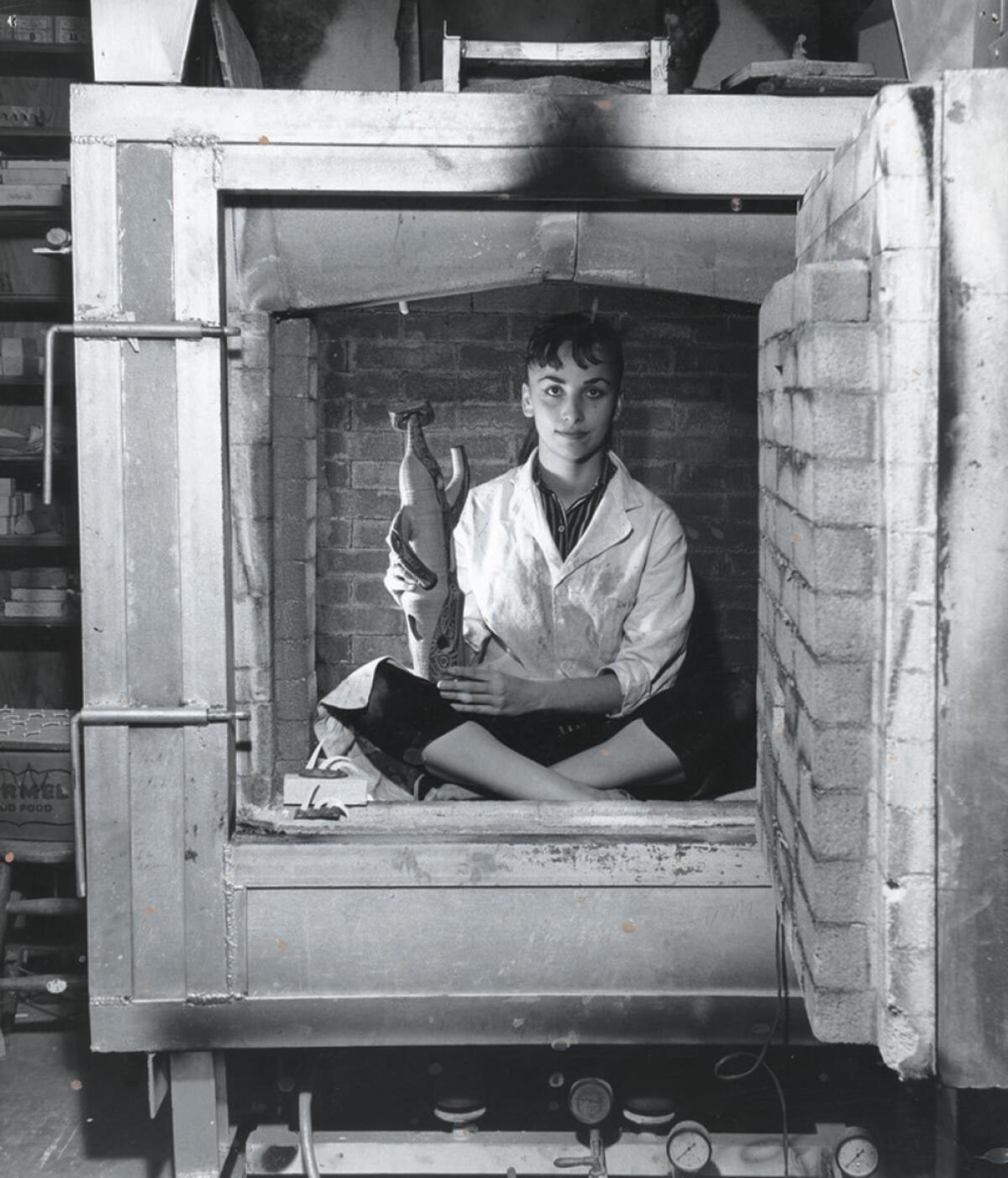

They are works by the Los Angeles ceramic artist, who for more than six decades has made art that eludes easy categorization. During a period in the 20th century, when other ceramicists were exploring the abstract, De Larios was creating curious creatures. Where others went minimal, she composed rich mosaics of intricate color and form. She created work inspired by pre-Columbian pottery and ancient Japanese funerary sculpture, yet her work felt resolutely Modern.

“I had to follow my own dream,” she says matter of factly. “I really didn’t care what others were making.”

She was a woman of color who had to make a way for herself at a time when there wasn’t a natural path.

— Allison Agsten, director, Main Museum, on Dora De Larios

Her singular path as an artist will be traced in a solo exhibition at the Main Museum in downtown Los Angeles next month. “Dora De Larios: Other Worlds” will gather works from throughout her career — sculptures, mosaics and functional tableware, including a set of majolica dishes she created for the White House in 1977. The show will also serve to inaugurate the museum’s newly renovated 2,800-square-foot mezzanine gallery.

“What’s so special about her is that she is forever learning,” says Main Museum director Allison Agsten. “There is such a vulnerability to the way she presents her work. She says, ‘I only got great at this in my seventies.’ She never stopped working — it’s a career marked by unflagging activity.”

That activity has extended to designing a permanent outdoor piece for the Main Museum — a design that will be etched into a concrete access ramp to be added to the building sometime this year.

De Larios has worked on all of this despite her declining health. After a prolonged battle with cancer, she is now in hospice. She conducts our interview (which took place late last year) stretched out on a recliner in her Culver City home, surrounded by the myriad artifacts of her storied life: books, works of art, family snapshots taken on jaunts around the world.

But even as her body fails, and her phrases are punctuated by occasional breathlessness, De Larios’ mind and wit remain sharp. She is concerned that I have something to drink when I arrive. She debates glazes with her daughter, Sabrina Judge, with whom she opened the ceramics company Irving Place Studio in 2012. She asks for a piece of paper to sketch out a bird that has popped into her imagination.

At one point, I gently ask if she minds revealing her age.

“I’m 84!” she replies enthusiastically. “I know I look good for my age. I’m just repeating what everyone else says. It’s my Hispanic genes!”

She looks damn good: close-cropped gray hair frame an elegant mestizo profile and a toothy grin — a Mexican American woman who singlehandedly willed her career into existence in the ‘50s displaying resolute strength to the end.

I had to follow my own dream. I really didn’t care what others were making.

— Dora De Larios

De Larios’ basic biography has by now been relatively well documented: Born in Boyle Heights in 1933 to a pair of Mexican immigrants, the artist went on to attend USC, where she graduated with a degree in ceramics in 1957.

Two things shaped her youth in indelible ways: her family and art.

Her father, Elpidio De Larios, was a turbulent presence. “In Spanish, they have that saying, that he was the light of the street and the darkness of the house,” she explains. But he was a lover of culture — and he passed on this affinity to his daughter, taking her on regular pilgrimages to see artifacts and monuments.

This included a trip to the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, where the 6-year-old Dora was seduced by a massive 13th century monolith bearing an Aztec calendar (a piece known as the “Piedra del Sol,” or rock of the sun). And there was the ride up to the De Young Museum in San Francisco in the late 1940s to see an exhibition of works that had once been secreted away by the Nazis in a salt mine.

“It was the first time I saw Rembrandt,” De Larios says with wonder. “It was fabulous, fabulous.”

She came to clay in a ceramics class at Dorsey High School in South Los Angeles.

“I liked that you could smash it up,” she says, “and then as long you didn’t fire it, you could reuse the material over and over again.”

Her enthusiasm for it was nurtured by a ceramics teacher at Dorsey.

“She gave me the keys to the studio. And everyday I worked after school until the janitor would come and say, ‘OK, it’s time for you to go home.’”

When De Larios graduated from high school, she was offered scholarships to attend the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland (now the California College of the Arts) and the Cranbrook Academy of the Arts in Michigan. But her father insisted she remain in Los Angeles — “I was young and couldn’t stand up for myself,” she explains — so she enrolled at USC, which had come through with a partial scholarship.

The school wasn’t a natural fit. De Larios was the rare Mexican American student on the largely white campus. And she often felt a bit the beatnik outcast on a campus that was all football and sunny cheerleaders.

“I dressed in black all the time and tried to look very moody,” she chuckles. “I would walk around campus like this little tarantula.”

But her studies there were nonetheless formative. De Larios learned from key 20th century ceramicists such as Susan Peterson, who was influenced by American Indian designs, and Otto and Vivika Heino, Americans of Finnish ancestry who would later gain international fame and wealth for a butter-yellow glaze formula that mimicked a Chinese glaze thought to be lost to the ages.

De Larios was also exposed to the work of important Japanese artists such as potter Shoji Hamada, a key figure in the mingei folk art movement, which sought to find beauty in the everyday. As a result, she developed a keen interest in Japanese design, with its devotion to material and line.

“I’m not subtle, but I love subtlety,” De Larios says of Japanese ceramics, “the delicacy, how patterns are interpreted.”

By the time De Larios graduated from USC, she was ready to take things into her own hands — often making opportunity when there was none to be found.

Soon after she graduated, she got right down to work — producing a range of functional and decorative pieces. As one well-told story goes, De Larios once loaded her car up with a pile of her ceramics and drove to San Francisco, where she demanded that the staff at Gumps, the luxury retailer, examine her wares. They not only took her on, they sold out of her work.

In the 1960s, she helped establish Irving Place Studio (for which her current company is named) with fellow ceramicist Ellice Johnston. There, the pair, along with four other women artists, shared space and resources.

“They shared a kiln and a glazing booth,” Agsten says. “But they also shared recipes and they helped take care of each other’s kids. She helped create a way for women to work and make money. They had biannual sales.

“She was a woman of color who had to make a way for herself at a time when there wasn’t a natural path.”

If at first De Larios had gone largely unacknowledged by galleries or the critical press, recognition eventually came.

By the 1970s, the artist was taking on major architectural commissions: a ceramic mural for the Compton Library and a cast cement monument for a park in Japan — a gift from the city of Los Angeles to its sister city Nagoya.

“I once got a call from Millard Sheets,” she recalls. “He said, ‘We have this huge project. It’s a $10-million budget. I want you to be the lead artist in charge of the textural design.”

That project consisted of a mind-boggling, roughly eight-story, 18,000-square-foot mural — yes, that’s right, 18,000 square feet — in the atrium of Disney’s Contemporary Resort in Orlando, Fla. The design was by Mary Blair. De Larios developed the mural’s rich color and texture.

“They tried to take it down once,” she remarks casually. “People had an uproar over it.”

To this day, the mural stands.

That same decade, she was commissioned by the Craft & Folk Art Museum to make a set of tableware for an undisclosed VIP client. The job: create a set of 12 table settings in less than 40 days. De Larios took it on — creating not one, but two sets of delicately hand-painted dishes laced with indigenous-style patterns, in case the first set didn’t turn out perfectly.

“It was crazy,” she says with a smile.

The mysterious client? None other First Lady Rosalynn Carter, who had commissioned 14 artists to create place settings for the White House. The dishes debuted at a special luncheon honoring American craft in 1977. (The Main Museum will have a set on view.)

In recent years, De Larios has begun to draw recognition not just for her high level of craft, but for the aesthetic innovations of her work.

In 2009, the Craft & Folk Art Museum staged the retrospective exhibition “Sueños/Yume: Fifty Years of the Art of Dora De Larios.” The catalog for that show describes an artist who “moves easily from abstraction to the realistic, to a stylistic or mythological dimension.”

At the moment, a pair of her sculptures are also on view in the PST: LA/LA exhibition “Found in Translation: Design in California and Mexico, 1915-85,” through April 1 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Show co-curator Staci Steinberger notes that many artists in the 20th century made ceramics inspired by pre-Columbian motifs: “Much of the work that was coming from California was very exotic-looking.” But De Larios’ work bears a quiet familiarity and grace. “She was looking into her own heritage,” Steinberger explains.

She was digesting other influences in interesting ways, too.

“There is that deep interest in Japanese ceramics,” Steinberger says. “She draws from that. She grew up in a Japanese neighborhood and that cemented her interest in Japanese culture. She is a quintessential Los Angeles artist — looking at the things that make L.A. L.A., and incorporating that into her work.”

De Larios is not one to spend too much time taking stock of her accomplishments — seeing each day as yet another possibility to test out new possibilities.

“A lot of my friends that are no longer making clay, they said they got bored,” she says. “I don’t understand that. There is so much to learn. But they’re bored. I want to slap them!”

She laughs.

The formula, she says, is really quite simple: “Every day. You show up. You do your work. You rest. You eat. Every day.”

De Larios may be too frail to throw clay. But as long as she can, she will show up — to the last day.

“Dora De Larios: Other Worlds”

Where: Main Museum, 114 Fourth St., downtown Los Angeles

When: Feb. 25 through May 13

Info: themainmuseum.org

“Found in Translation: Design in California and Mexico, 1915–1985”

Where: Resnick Pavilion, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 5905 Wilshire Boulevard, Los Angeles

When: Through April 1

Info: (323) 857-6010, lacma.org

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

ALSO

At 81, ceramic artist Dora De Larios still creates for new audiences

An exhibition on L.A.'s queer Chicano networks shows how California artists connected with the world

L.A. artist Rodney McMillian peels back the facade on the ultimate symbol of power: the White House

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.