Why the exterior of D.C.’s soon-to-open African American museum is an exciting sign of what’s inside

Reporting from Washington — The last 18 months have seen a bonanza of museum openings around the U.S. There was the behemoth expansion of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in the spring. The Whitney Museum’s move to downtown Manhattan in 2015. And the new Broad, in Los Angeles, last fall.

But the biggest of them all is the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History & Culture, which opens in Washington, D.C., late next month.

For the record:

1:43 p.m. Nov. 7, 2024An earlier version of this article stated that Smithgroup is a Washington architecture and engineering firm. It is a national firm with headquarters in Detroit

Designed by David Adjaye, the British Ghanian architect who also designed the Museum of Contemporary Art in Denver and is currently at work on a new structure for the Studio Museum in Harlem in New York City, the 400,000-square-foot exhibition hall, covering the breadth of African American history and culture, occupies a prominent corner on the National Mall.

The building is a stark — and welcome — departure from the neoclassicism for which D.C.’s architecture is known. And while it is not yet complete (scaffolding still covers the building’s broad entrance), the museum nonetheless cuts a daring profile on the Mall, where its stacked trapezoidal forms appear to erupt from a grassy plain between the obelisk of the Washington Monument and the columnar façades of the Herbert Hoover Commerce Department Building. (The museum literally emerges from underground: Roughly 60% of the building’s 400,000 square feet is below grade.)

During a trip to D.C. this last weekend, I was able to take in the exteriors of Adjaye’s design — which he has executed in collaboration with the Freelon Group, a design office based in North Carolina, as well as Davis Brody Bond, of New York and D.C. The architecture and engineering firm Smithgroup is also involved.

If the insides are as good the outside, there is reason to be excited about this unusual building.

The museum is veiled in a bronze-colored cast-aluminum lattice (evocative of iron work once done by enslaved craftsmen) that looks moody in cloudy weather and shimmers in sunlight. It’s a building whose demeanor is constantly shifting.

It’s not a story of a people that were taken down, but actually a people that overcame and transformed an entire superpower into what it is today.

— David Adjaye, architect

The structure is solemn, respectful of the difficult history it must commemorate. (The National Mall itself once contained so-called slave pens, where individuals were held prior to auction.) But its triumphant silhouette also nods to African American achievement in areas of politics, society and culture. Among the 34,000 objects in the permanent collection wil be personal items belonging to abolitionist Harriet Tubman, a Jim Crow-era railroad car and the Parliament Funkadelic mothership. Groovy.

Sign up for our free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

As Adjaye told Smithsonian Magazine in 2012, “It’s not a story of a people that were taken down, but actually a people that overcame and transformed an entire superpower into what it is today.”

I was unable to see the NMAAHC’s subterranean insides, but I did get to visit another Adjaye project in D.C.: One of two public libraries the architect completed in 2012.

The Francis A. Gregory Neighborhood Library in the city’s Southeast district has been popping up in magazines and design blogs since it first opened four years ago — for good reason.

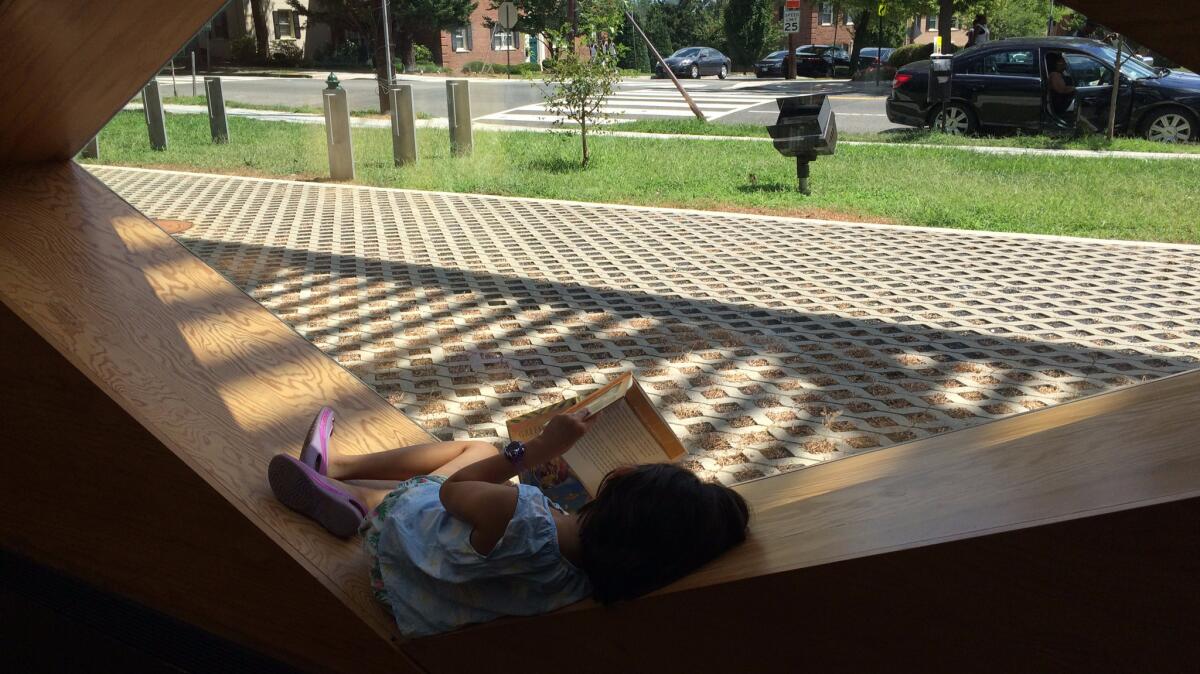

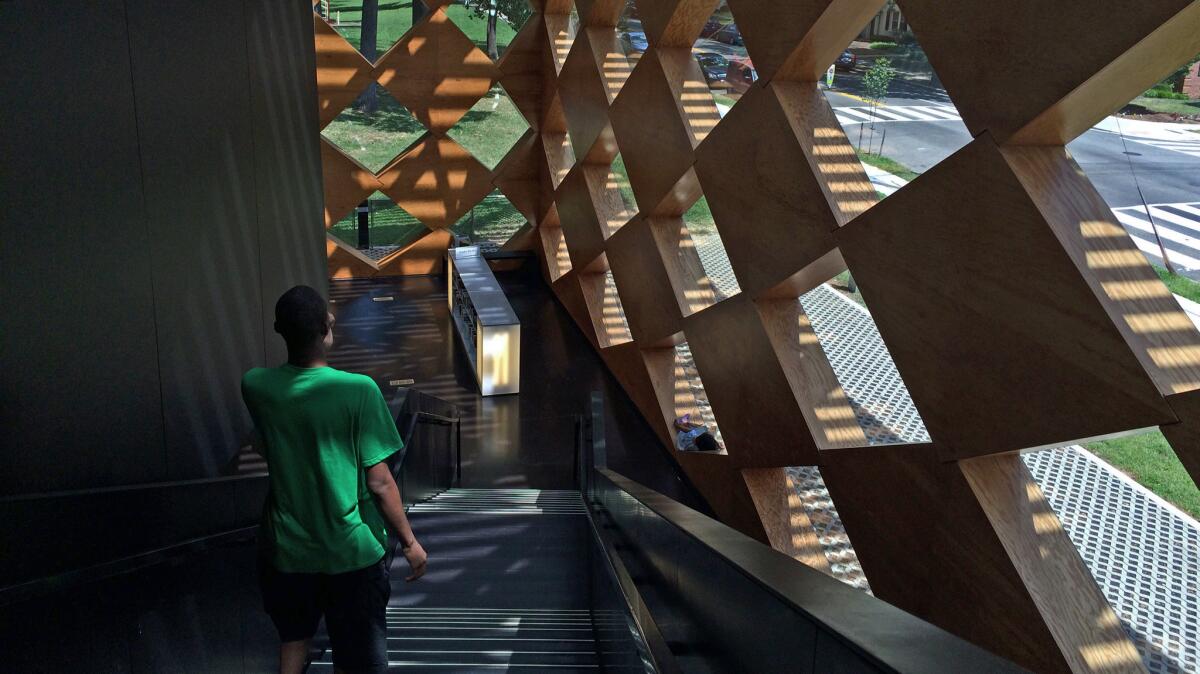

It is exceedingly photogenic, featuring a sleek glass skin and a checkered architectural motif, constructed out of economical plywood, that echoes — on a large scale -- the repeating patterns of terra-cotta screen blocks or concrete screens (of the sort employed in all kinds of architecture, from the Indo-Islamic to the Modernist American Cement Building in Los Angeles).

The building, blessedly, lives up to all the photography.

The wooden trellis design breaks up sunlight for a dappled effect that is quite cinematic. But it also maintains a sense of openness to the outdoors, which includes a leafy park to the library’s rear. And at 2,500 square feet, the building is intimate, an inspiring place to study, read or play educational video games (which is what a group of kids were doing when I popped in on a Sunday afternoon).

The ground floor, geared to adults, features high ceilings, rows of stacks, a quiet study area and a computer lab. The second story, built on a smaller scale, harbors the children’s library, which features a storytelling area and other gathering spots. All of it came together for the modest price tag of $13 million.

The library is nowhere near in scale to the $540-million museum Adjaye has in the works on the National Mall. But its plays on light and dark, and its generally thoughtful design — Washington Post critic Philip Kennicott describes it as a good place to “sit and reflect and read” — certainly have me looking forward to the museum’s imminent opening.

For more on the National Museum of African American History & Culture, see the Washington Post’s photographic preview of the new building, plus Citylab’s roundup of the most interesting details related to the new facility and its collections. Also, Kriston Capps has a pretty terrific story in the Atlantic about how the museum is rebuilding a former slave’s cabin inside its galleries.

+++

National Museum of African American History & Culture

Where: National Mall, Washington, D.C.

When: Opens to the public on Sept. 24

Info: nmaahc.si.edu

Find me on Twitter @cmonstah.

ALSO

Lonnie Bunch reflects on journey to national African American museum

Why the Rio Olympics opening ceremony matters

What Dominique Moody’s tiny ‘Nomad’ house says about the environment and African American design

Tom Hanks lends a hand to Eisenhower Memorial in Washington

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.