Why so many Mexicans revile the Colonial Californiano architectural hybrid that spread from SoCal

Reporting from Mexico City — It is Mexico as filtered by California and then re-appropriated by Mexico in a different guise.

The story of the architectural style known as Colonial Californiano is the story of ideas ricocheting between two cultures in unlikely ways. And it is one that leaves its mark on Mexico City to this day in the form of apartment buildings and grand private homes — neocolonial structures whose immediate design antecedents lie not in Mexico, but, ironically, in the United States.

“This was a style for the newly rich, aspirational Mexicans who wanted some kind of national expression,” says Wendy Kaplan, head of decorative arts and design at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. “But who also wanted to show how up-to-date they were.”

But even though Colonial Californiano was commercially popular in its heyday in the early 20th century, it was almost universally reviled by Mexican scholars and avant-garde architects.

“They hated it because people thought it was Mexican,” says Cristina López Uribe, a member of the architecture faculty at Mexico’s National Autonomous University. “But it was really a copy of Spanish Revival” — which hailed from the United States.

California, to be specific.

In Mexico we have had the misfortune of the influence of California Colonial … the use of which in our country is so absurd.

— Luis Barragán, architect

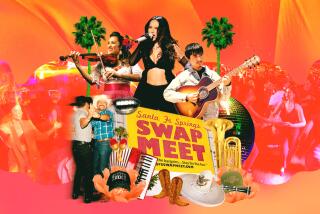

The curious emergence of Colonial Californiano is a tiny sidebar in the comprehensive design exhibition “Found in Translation: Design in California and Mexico, 1915-85,” on view at LACMA through Sunday. But it’s an intriguing one.

“It is a very complicated and fascinating story,” says Kaplan, who co-curated the show.

And it is one that begins at the turn of the 20th century.

California, in search of an architectural identity for itself, starts to look to its Mexican past, fusing elements of colonial design into early Modern structures: white stucco, red-tile roofs, arched openings and iron-grille windows. It is the colonial stripped down and made breezy, redefined for an era of mass media and the automobile.

That style, known as Spanish Colonial Revival, came to define the Southern California landscape. In fact, it was described by one U.S. architect of the 1920s as “a true California type.”

Private homes, public spaces (the “El Paseo” walk in Santa Barbara, for example) and civic buildings (the Beverly Hills water treatment plant designed by Arthur Taylor in 1928, later to become the Fairbanks Center for Motion Picture Study) all sprung up in various shades of Spanish Colonial Revival.

It was design that embodied optimism, redolent of orange blossoms and easy sunshine. And it spread beyond California through various means: via architects who spent time in Los Angeles and then traveled elsewhere, and through glossy magazines that distributed images of movie star homes far and wide. Howard Hughes, Charlie Chaplin and Dolores del Rio all, at one point or another, had pads designed in the Spanish Colonial Revival style by architects such as Wallace Neff, who helped popularize the style.

It was just a matter of time before the style made the jump elsewhere — and that elsewhere was early 20th century Mexico, where it was promptly adapted as Colonial Californiano by developers and architects seeking to sell designs that felt both fashionable and traditional.

It is the colonial stripped down and made breezy, redefined for an era of mass media and the automobile.

In the tony Mexico City district of Polanco, architect Francisco J. Serrano, who had a close connection to Los Angeles (he frequently traveled to the city to buy films for a cinema he owned) designed the undulating Pasaje Polanco, a mixed-use apartment complex completed in 1939. The Modern design bears Spanish Colonial Revival elements such as red-tile roofs, arched passageways and bright ceramic tile details.

A few blocks to the south, at the corner of Luis Urbina and Alejandro Dumas streets, architect Eduardo Fuhrken Meneses (who for a time worked as a set builder for Paramount in Los Angeles) adopted the style for the prominent home of lottery magnate Elias Henaine. Interestingly, many Colonial Californiano homes were built and occupied by immigrants — serving as visual badges of Mexican-ness. Henaine, for example, was of Lebanese origin.

On a bright Sunday morning last year, López took me on a walk through Polanco to visit these and other extant examples — including the grand Colonial Californiano home that now serves as a Mexico City outpost of Japanese-fusion chain Nobu.

López, who contributed an essay on the synergies between the architecture of Mexico and California for the very worthwhile “Found in Translation” catalog, explains why the style was abhorred by so many Mexican Modernists.

During the early 20th century, Mexican design was also in the process of revisiting its colonial architecture — albeit as a tool for building national identity in the wake of the Mexican Revolution. Spanish Colonial Revival, however, took many liberties with these historic forms.

In Mexican colonial traditions, a building typically surrounded an outdoor patio; in Spanish Colonial Revival, buildings were often sited at the center of the property and surrounded by garden. Spanish Colonial Revival designs were often asymmetrical and included elements such as a tower (torreón), basements and pitched, red-tile roofs — architectonic flourishes that were not in use during the Mexican colony.

And there was the issue of the name: Spanish Colonial Revival, which took its lineage from Europe rather than from Mexico.

“The ‘Mexican’ had a primitive connotation — we were the aggressors of the Mexican Revolution,” notes López. “So when they establish their style in the United States, it was best to establish a connection with the European rather than the Mexican.”

By naming the style Spanish Colonial Revival, it had the effect of erasing Mexican influence from the architecture of California.

When Santa Barbara’s El Paseo debuted in the 1920s, for example, it was described as “A Bit of Andalusia” by the Santa Barbara Daily News. Never mind that architect James Osborne Craig had specifically based his design on a structure in the Mexican city of Cuernavaca.

This was a common ploy, as former Times architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne noted in his review of “Found in Translation.”

“When Myron Hunt and George Washington Smith produced their most ambitious Spanish Colonial designs between 1900 and 1930, they weren’t just gazing back to Southern California’s Spanish and Mexican pasts; they were pointedly giving a foothold to a respectable Eurocentricism here,” he wrote. “It was commonplace to ‘misidentify’ Mexican artifacts as Spanish ... precisely because of this preference for a European lineage over a pan-American one.”

Mexican Modernist Luis Barragán noted the absurdity of the situation at a California architectural event in 1951.

“In Mexico we have had the misfortune of the influence of California Colonial … the use of which in our country is so absurd, since this style was brought to Mexico, and from Mexico to California,” he stated dryly. “Los Angeles and Hollywood then exported it once again to Mexico as California’s Spanish Colonial.”

The Mexicans aren’t the only critics. In the 2003 documentary “Los Angeles Plays Itself,” Thom Anderson describes Spanish Colonial Revival as being laden with “phony historicism.”

LACMA’s Kaplan says “Found in Translation” casts a light “on how much Mexican design and architecture have been left out of the history of California design and, of course, design throughout the United States.”

The exhibition also reveals the curious ways in which California shaped the architecture of places like Mexico City.

“When these were built, architecture was in its Modernist phase and many architects despised this style,” says López of the “Colonial Californiano” structures in Polanco. “It was usually done by engineers and developers … it was the style done in tourist neighborhoods.”

But time has passed and the kitsch of the past now has stories to tell about the ways in which ideas travel and evolve.

“They deserve to be studied,” says López.

Ersatz history, it turns out, can tell us as much about ourselves as the real thing.

“Found in Translation: Design in California and Mexico, 1915-85”

Where: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 5905 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles

When: Through Sunday.

Info: lacma.org

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

ALSO

What a big LACMA exhibition has to say about L.A.’s ongoing search for ‘civic identity’

From a TMZ tour bus to a seat at the Oscars: My search for elusive celebrity culture in Los Angeles

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.