Cheech Marin, a singular Renaissance man, talks about comedy, pottery, pot, art and his new memoir

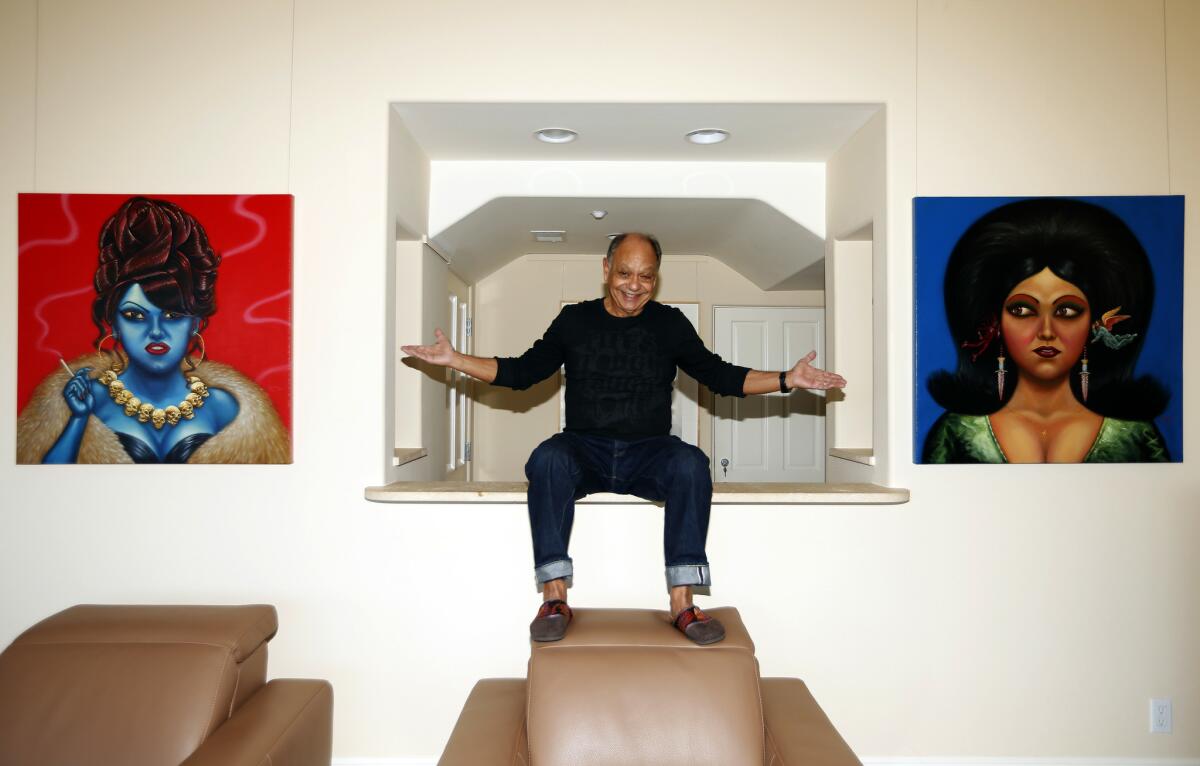

Pay a visit to the Pacific Palisades home of actor and comedian Cheech Marin and you may find yourself holed up in the bathroom, in the company of your affable host, having an impassioned conversation about painting.

Marin, an avid collector, has dozens of artworks dotting every corner of his hilltop home. There are canvases by Patssi Valdez in the hallway, an oversized painting of a Madonna by George Yepes in the foyer and, in the guest bathroom — where Marin has led a small clutch of guests — a series of surreal etchings by the late Los Angeles painter Carlos Almaraz.

“These are very rare,” says Marin, gesturing at a print in which a trio of feline heads float before a custard-colored sky. “The color, the way he captures these figures, the city, it’s the bomb.”

Marin is a singular type of Renaissance man.

Over the course of his 71 years, he has worked as a ceramicist and a music critic. He has been half of the stoner comedy duo Cheech & Chong. He has played cops on TV, bandits on film and myriad priests (such as the gun-toting padre in Robert Rodriguez’s 2010 vengeance flick “Machete”). He has created music albums for children, worked as a voice-over artist and made a name for himself as a voracious collector of art.

And now Marin — born Richard Anthony Marin in South Los Angeles — can add another title to the list: memoirist.

“It was a chance to write and make it intimate and put you there,” he says of his new autobiography, “Cheech Is Not My Real Name … But Don’t Call Me Chong,” as he settles into a broad couch on an outdoor terrace with Pacific Ocean views. “There’s a rhythm that you get — the words start making a rhythm, they’re your tones.”

Needless to say, Marin isn’t the sort of celeb to rely on a ghost writer. (He did, after all, work as a music reporter for a publication called Poppin as a young man in Canada, reviewing shows and interviewing various musical acts.)

“The writing took about nine months,” Marin says of the memoir. “It was get up early, get a cup of coffee and hit it. Not even read a newspaper. Just get up and hit it.”

That, he says, is when the words would spill onto the page.

“It’s like an accumulation of what my mind has been going through in my sleep,” he adds with a grin. “That’s when all the demons come out to dance in your dreams!”

We were both musicians. We knew when to highlight each other, when to play rhythm and when to play lead.

— Cheech Marin on working with Tommy Chong

Gretchen Young of Grand Central Publishing, an editor who has worked with comedians such as George Carlin and Larry Wilmore on their books, says she was impressed with Marin’s dedication to craft.

“When we met, he made it clear this would be his priority,” she said via telephone from New York. “And once he got into doing it, you could tell he was like a kid in a candy shop. He would give me updates. He’d ask questions: ‘Is this a better way to tell it? Or is that a better way to tell it?’”

In addition to developing his voice as a writer, the project has been an opportunity for Marin to revisit important moments in his life — the moments that don’t always make it into the magazine profiles.

There were his early years in a tough patch of South Los Angeles, where his father, a police officer, once shot a violent robbery suspect — a shooting that took place right outside the Marin family home.

“After a while it became just another shooting in the hood, and everything went back to normal,” writes Marin. “It never went back to normal for me. I had nightmares every night.”

In the wake of that incident, the family moved to Granada Hills in the San Fernando Valley, where Marin attended high school and college — and where he would cultivate a pair of cultural interests that would shape the rest of his life.

The first interest was music.

In conversation, Marin makes regular references to music, to things like tempo and rhythm. He has played guitar since he was 12. And in high school, in the early 1960s, he was a devotee of folk music. “I don’t know how authentic I was, being a Chicano singing about Gypsy Davy roaming the country-o,” he writes in the book. “I just liked singing and being in show business.”

His second interest was pottery, cultivated in the ceramics lab at Valley State College (now Cal State Northridge).

“I just fell in love with it,” he recalls. “The first time you center a piece of clay, you feel this force in the universe. I describe it in the book like this tuning fork went off in my loins. It’s where my recessive Mexican craft gene came out. It was like, ‘Vato!’”

In 1968, pottery and the Vietnam War led Marin to Canada.

In protest of the war, Marin defaced his draft card (he had Muhammad Ali sign it at an event), then publicly turned it over to a group from the Students for a Democratic Society, who opposed military intervention in Asia. In retaliation for these sorts of actions, a U.S. general called for individuals who vandalized or turned in their cards in to be reclassified as fit for military service — whether or not they had student deferments. (This was later declared illegal by a U.S. court.)

All of a sudden Marin was at the top of the draft list. He writes that he had no intention of going to Vietnam — so he went to Canada instead, where he found employment in the studio of potter Ed Drahanchuk in the mountains of Alberta.

It is these chapters that make for some of the most engaging reading, with Marin, a kid from L.A., learning how to survive northern winters in a small, wood-stove cabin in the Canadian Rockies.

“One day, Ed had shot a bear in front of the door of the studio and he’s, like, ‘We have to skin it,’” recalls Marin, an episode he also recounts in the book. “I’d never fired a gun in my life before moving to Canada. It’s, like, ‘What the…?’ And there’s this bear and Ed’s, like, ‘OK, grab a leg.’”

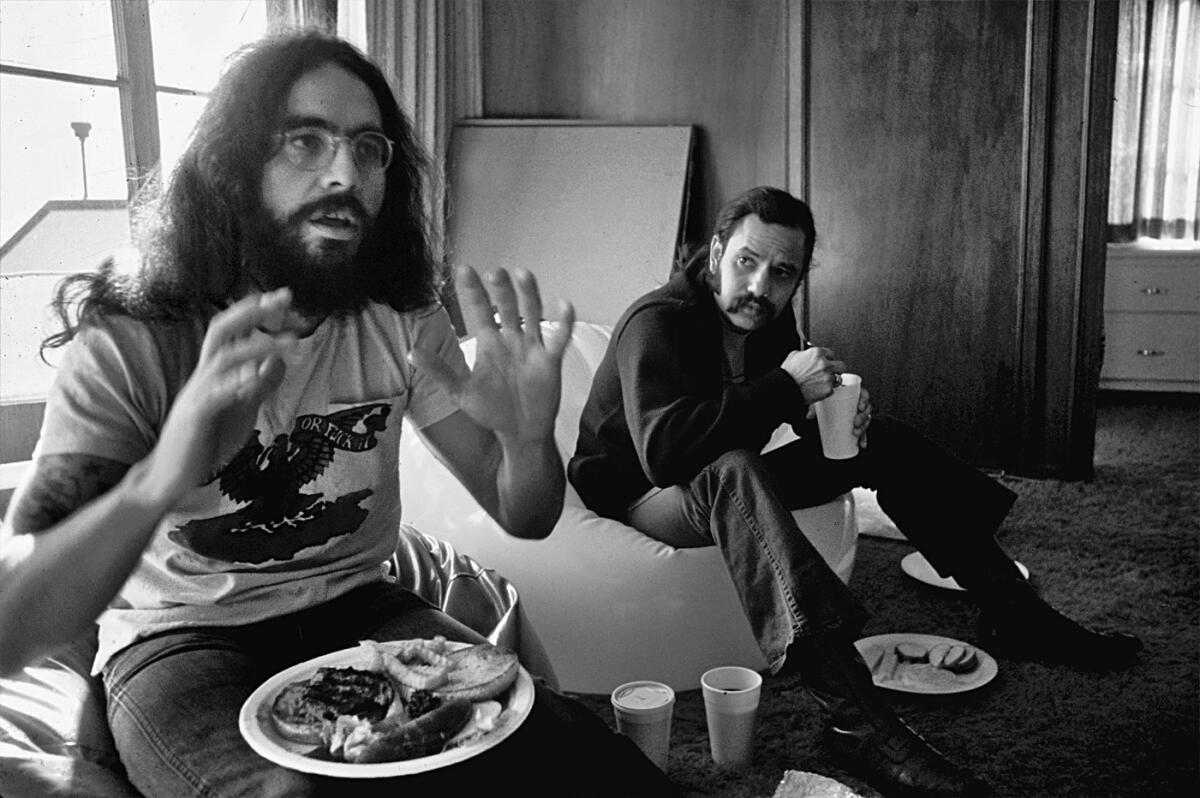

After the work ran out with Drahanchuk, Marin eventually made it to Vancouver — and that’s when his life truly changed. This was where the publisher of Poppin magazine, for which Marin had been dutifully churning out unpaid stories on the likes of Little Richard and Richard Pryor, introduced him to a local impresario by the name of Tommy Chong.

Chong’s look at the time, writes Marin, was “hippie-biker-Mongolian-weight-lifter.” His job? Operating a down-at-the-heels hippie burlesque called the Shanghai Junk.

“You can’t imagine what that thing was like,” says Marin with a laugh. “I can see it so clearly. I can feel the texture of the rug and how sticky it was. There was stuff happening in those bathrooms — people would be scoring drugs and getting hookers. And the act had a mime artist in the whiteface makeup and the beret. Nobody had any idea what he was doing there.”

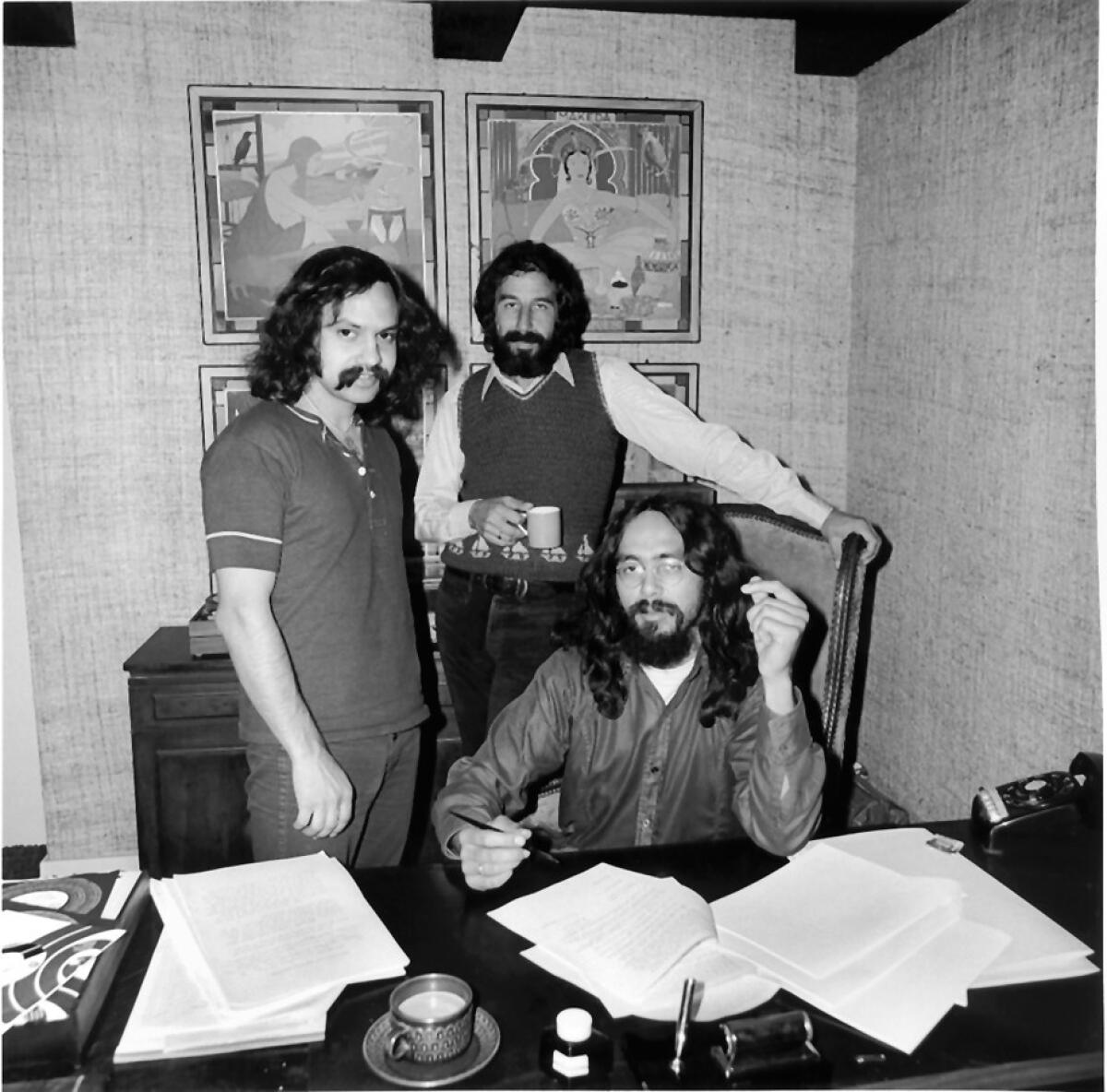

Chong hired Marin to help write material for this unusual revue. What followed is a story that is by now familiar: Cheech & Chong honed their improvisational act on the hostile stage of the Shanghai Junk in Vancouver before relocating to L.A., where they ultimately landed a deal with Dunhill Records.

From there, success came fast and furious: A Grammy Award for their second comedy album, “Los Cochinos.” The release of “Up in Smoke,” the 1978 film — one of the year’s top 20 box office grossers — which turned them into comedy and cultural icons. The dizzying array of club gigs and follow-up movies.

“Tommy and I were so attuned to each other that we could write for each other,” writes Marin of those days. “I could see his characters and he could see mine.”

“It’s like music,” says the actor of his and Chong’s collaboration (one that continues to this day despite some tense moments over the years). “We were both musicians. We knew when to highlight each other, when to play rhythm and when to play lead.”

In writing about that era in the book, Marin says he wanted to show that Cheech & Chong were not some cosmic accident. “We are artists, we work hard,” he says. “We have a subtle and unexpected art that is hugely popular.”

The duo may have made light of smoking pot (there’s a chapter about weed too), but they were hardly burnouts. “There is an endurance there,” says Marin. “I didn’t develop habits like drinking or [hard] drugs and Tommy was the same. He was very disciplined. He was a body builder.”

And their work, in its own peculiar way, addressed issues that went beyond pot jokes. Films like “Up in Smoke” served as an exploration of Los Angeles, a place where the journey (in a tricked-out vehicle) is the destination. Plus, it was comedy that presented Chicano culture to a broad audience in a way that was never didactic or self-conscious.

“I’ve always been a believer that if you make something very specific, you can make it very universal simultaneously,” says Marin. “People will feel the purity of emotion.”

“Cheech Is Not My Real Name” highlights Marin’s career since: His appearance in feature films such as "Born in East L.A.” and “Tin Cup,” his voice-over work on animated hits such “Cars” and the “Lion King,” and the cop role on “Nash Bridges” that provided him with enough financial security to seriously indulge his taste for collecting.

I’m working on rousing Chicanos ... to be empowered and proactive in their relationship with museums. It’s a hard road.

— Cheech Marin

In the 1970s, he had regularly acquired early 20th century Art Nouveau design objects: rare prints and vintage furnishings — which he retains to this day. (“It was very hippie-esque,” Marin says of his early attraction to it. “I was making pottery and hanging out with stained-glass makers and they were super into it.”)

But in the 1990s, he turned his attention to Chicano art. In his memoir, Marin chronicles how important it has been to him to have work by Chicano artists presented in the mainstream. His collection — which includes more than 700 objects — has been shown in museums all over the country, including the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

“The way museums work,” he says, “is that whoever pays for the museum decides what goes inside. So I’m working on rousing Chicanos to do the same thing, to be empowered and proactive in their relationship with museums. It’s a hard road. Chicano philanthropy doesn’t really exist, but it eventually will.”

Ultimately, the memoir has given the comedian a taste for doing more writing.

“I’m writing a collection of essays on Latino culture,” he says. “It’s called ‘We Come in Peace and We Have You Surrounded.’”

“I’m writing an essay called ‘English Only’ that looks at the consequences of English only,” he adds.

What kind of conclusions does the piece come to?

“I can’t tell you,” he says with a laugh. “Read the book.”

::

Global Voices: Cheech Marin in conversation

Where: The Broad Stage,1310 11th St., Santa Monica

When: 7:30 p.m. Thursday

Price: $60 to $90

Contact: thebroadstage.com and cheechmarin.com/memoir

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

ALSO

On the trail of Yma Sumac: The exotica legend came from Peru, but her career was all Hollywood

Curator Nato Thompson shines a light on art and the culture wars in 'Culture as Weapon'

Lourdes Ramos named president of the Museum of Latin American Art — first Latina to hold the post

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.