Review: ‘Confederacy of Heretics’ a delicate task

It’s difficult to imagine a more delicate curatorial task than the one Todd Gannon, Ewan Branda and Andrew Zago faced in putting together “A Confederacy of Heretics: The Architecture Gallery, Venice, 1979.”

The exhibition, running through July 7 at the Southern California Institute of Architecture, is the first show to open as part of the Getty-funded series “Pacific Standard Time Presents: Modern Architecture in L.A.”

The specific focus of “Heretics” is a series of exhibitions and lectures that young architects connected to SCI-Arc organized in fall 1979, when the school, now downtown, was based in Santa Monica. In a broader sense, its subject is the experimental architecture culture, with its hothouse rivalries and anti-establishment energy, that thrived on the Westside in the 1970s and ‘80s.

FULL COVERAGE: Pacific Standard Time

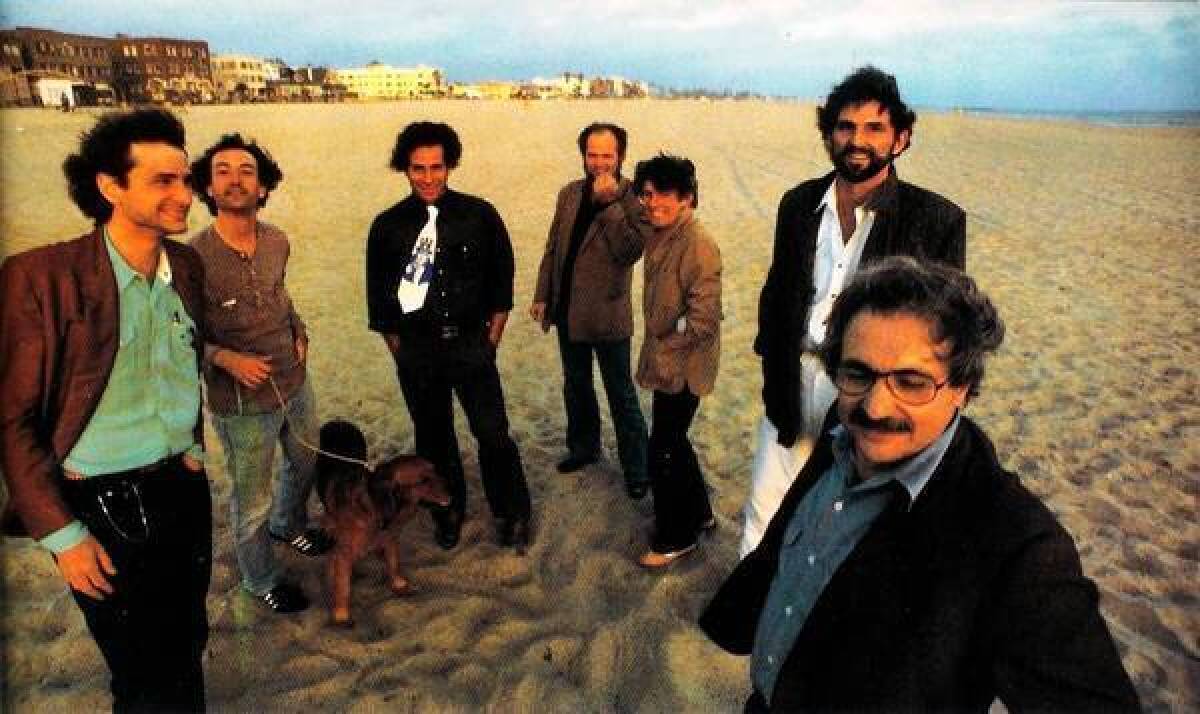

And here’s where things get tricky. Several of the men (and they were all men) who took part in those shows have not only gone on to become some of the most prominent architects in the country but also to run SCI-Arc. One, Eric Owen Moss, is the school’s director. Two others, Frank Gehry and Thom Mayne, sit on the board of trustees.

Two of the curators, meanwhile, Gannon and Zago, are on the SCI-Arc faculty. On top of that, the architects featured in the exhibition have always been unusually active in shaping the story, and tending the myths, of their own professional youth. And in fact a rather biting email about the show I received from Moss just a few hours before it was due to open — more on that later — suggests some of the peculiar constraints the curators have been operating under.

While Gannon, Branda and Zago have been brave to stride directly across this particular minefield, in the show you can spot more than a few places they paused to tighten their helmets or plot out the safest route. The ambitions, shifting allegiances and self-promotion that drove this work are muffled, and what comes to the fore instead is the pure virtuosity of the projects and an emphasis on how, rather than why, they were created.

“A Confederacy of Heretics” is at heart the story of a short-lived gallery that Mayne, who was then partner with Michael Rotondi in the firm Morphosis, set up in his own Venice home, not far from the original SCI-Arc building.

In late 1979 that gallery was the site of nine consecutive weeklong exhibitions, each focusing on the work of an up-and-coming L.A. architect or collaborative and each accompanied by a lecture at SCI-Arc from the star of that week’s show. Coy Howard, a young architect whose work was not shown, gave talks to open and close the series.

CHEAT SHEET: Spring Arts Preview

The architects were then mostly in their 30s and early 40s; Gehry, who had just turned 50, was the oldest. SCI-Arc itself, founded in 1972, was just 7 years old. Each of the exhibitions was reviewed enthusiastically by John Dreyfuss, who was then this newspaper’s architecture and design critic.

From the start the members of this loose collective rejected what they saw as the stale orthodoxies of late-modern architecture, which by then was nearly synonymous with sleek, risk-averse buildings for corporate clients. But they also tacked away from East Coast architects like Robert Venturi, whose work in those years was moving in the direction of what would become mainline postmodernism.

“Heretics” is divided into two parts. A section upstairs, in the SCI-Arc library, introduces the basic chronology of the 1979 shows and includes superb drawings by Frederick Fisher, Roland Coate Jr. and Frank Dimster as well as Craig Hodgetts and Robert Mangurian, who called their firm Studio Works.

In a small suite of downstairs galleries, wall panels explain the various ways in which the architects toyed with perspective in their drawings and models — a kind of inside-baseball analysis that strikes me as a way to sidestep, consciously or not, larger and more contentious themes. Also featured here are designs by Morphosis, Moss and Howard as well as terrific black-and-white photographs by Grant Mudford of Gehry’s own remade bungalow in Santa Monica.

Some of these projects — Moss’ Pinball House, for example — are colorful and playful, with an undercurrent of rebellious energy. Others are tougher and more aggressively unorthodox.

Perhaps most intriguing of all is a series of stamps, produced by Mayne and Rotondi, showing Morphosis designs. (They are displayed here in framed sheets.) As if to declare the founding of a new architectural principality, with its own laws and customs, the architects gave the stamps a remarkably authentic look; according to Gannon, they even ran them through a sewing machine to perforate the edges. Zago, who designed the exhibition, blows these stamps up to giant scale and turns them into a kind of creased wallpaper at the entrance to the lower-level galleries.

SPRING ARTS PREVIEW: Architecture | Dance | Theater

For the most part the curators treat this fascinating material — and these complex personalities — rather gingerly. And it’s not hard to understand why. As I was emailing with Moss the week of the show’s opening, I asked him offhandedly what he thought of it. I have known Moss for several years, but I wasn’t prepared for the broadside I got in return, written in the architect’s usual efficient and insistent style.

He later told me I was free to quote from the email. Remember, as you try to measure the oddity of what follows, that he is SCI-Arc’s director and helped plan the show in its earliest stages; at least indirectly it is his exhibition as well as the curators’.

“Gannon/Zago had an opportunity to make a definitive statement re meaning of work from that time,” he wrote to me. “Missed the opportunity.” He went on to complain that the major themes he felt the show ought to have explored — the influence of the Vietnam War and the counterculture, the relationship between L.A. architects and the East Coast establishment — were “untouched,” “unmentioned” or worse.

“Tell us something we don’t know,” he wrote by way of conclusion. “Give us a new frame of reference with which to think about the work. Otherwise not living up to the 1970’s tale of an LA architecture renaissance.”

The show does seem overly restrained in spots (or slyly subtle, if you want to give the curators a bit more credit). But Moss doesn’t seem to realize or be willing to acknowledge that one main reason for those qualities is his own tendency to send emails like that one.

Indeed, his take on the exhibition seems almost perfectly to encapsulate the many challenges the curators confronted in mounting it — to say nothing of the complicated, proprietary attitude Moss and the architects he came of age with in Los Angeles have always shown toward the meanings of their early work and their own substantial fame.

MORE

INTERACTIVE: Christopher Hawthorne’s On the Boulevards

Depictions of violence in theater and more

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.