Review: ‘Border Door’ provided a poetic welcome to immigrants 30 years ago. An art show brings back its message

An otherwise modest group exhibition at the Vincent Price Art Museum at East Los Angeles College is striking — and timely — if only because it commemorates the 30th anniversary of one short-lived, poetically potent art installation.

Richard Lou’s site-specific 1988 “Border Door,” erected at the perennially charged U.S.-Mexico boundary, is a landmark sculpture created during the artist’s affiliation with San Diego’s famed Border Art Workshop. Today, as a caravan of Central American refugees fleeing poverty and violence in their home countries has finished crossing the Tijuana border seeking asylum, the memory of Lou’s long-lost portal has new life.

The border walls and other barriers we see today didn’t start being vigorously erected until the 1990s. Before then, an occasional fence delineated sections along the 1,989 miles of international border. At a breach in a tumble-down barbed-wire fence at windswept Otay Mesa, not far from Tijuana International Airport, Lou erected a wooden door on a hinged metal frame.

Row upon row of keys, 134 in all, hung from nails hammered into the door on the Mexican side. The door opened only one way — into the United States. Lou’s sculpture was a symbolic gesture of migratory welcome in a harshly contested landscape.

The artist’s choice of that specific, hardscrabble Otay Mesa site endowed the open door’s functionality with a wryly absurdist twist: To cross over the border from Mexico to the United States, a person could just as easily walk around the sculpture, key or no key.

For that matter, with enough money, a migrant could just get a flight from the nearby Tijuana airport and then overstay their visa. (For more than the past decade, that has been the preferred method for undocumented immigrants to the U.S. from any country.) Poverty and xenophobia thrum within the site-specific sculpture’s social mix.

One source of its power is that the work is simplicity itself. Or, rather, was: The sculpture lasted just two days, recorded in Jim Elliott’s widely shown black-and-white documentary photographs, before the Border Patrol tore it down.

Lou’s work was initiated as part of an annual Border Art Workshop exhibition at Centro Cultural de la Raza in San Diego’s Balboa Park. Necessary permits had been obtained for the off-site installation. The fact that the Border Patrol hauled it away anyhow spoke mostly of the power that an artistic symbol can have.

It’s worth looking at those photographs again at the Vincent Price Art Museum. The path around the sculpture, side-stepping derelict razor-wire battered by weather or trampled by unseen animals, is bleakly demeaning. Beneath cloud-filled skies, the “Border Door” framed human passage with humble dignity.

Lou self-identifies as Chicano, but the traveling VPAM show, organized by the Arizona State University Art Museum in Tempe, puts him into a slightly different context. “Soul Mining,” as the small show is titled, considers Chinese immigration to the Americas, highlighting a different aspect of the artist’s own Chinese Mexican heritage.

During an earlier authoritarian era, Congress in 1882 passed a law forbidding immigrants from China to enter the United States and hounding thousands of those already here to leave. The California Gold Rush was over, the Golden Spike completing the transcontinental railroad had been driven and the era that Mark Twain dubbed the Gilded Age was in full swing. Chinese labor was instrumental to all of them.

All that gold and gilding put a viewer of Lou’s “Border Crossing” in mind of the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor. Emma Lazarus’ sonnet, “The New Colossus,” with its imagery of a lifted lamp lighting immigration’s “golden door” to America, was written a year after the racist law passed. Washington had decided that it was time to officially marginalize Chinese laborers, whose back-breaking work made possible much of the Gilded Age’s obscene wealth gap between rich and poor. The Chinese Exclusion Act banned all immigration from China for a period of 10 years — the first federal law to forbid U.S. entry to an ethnic group.

“Soul Mining” is too small — just 15 works by 12 artists made over three decades — to rise to the ambitious occasion. But, in addition to “Border Door,” it does include some provocative examples.

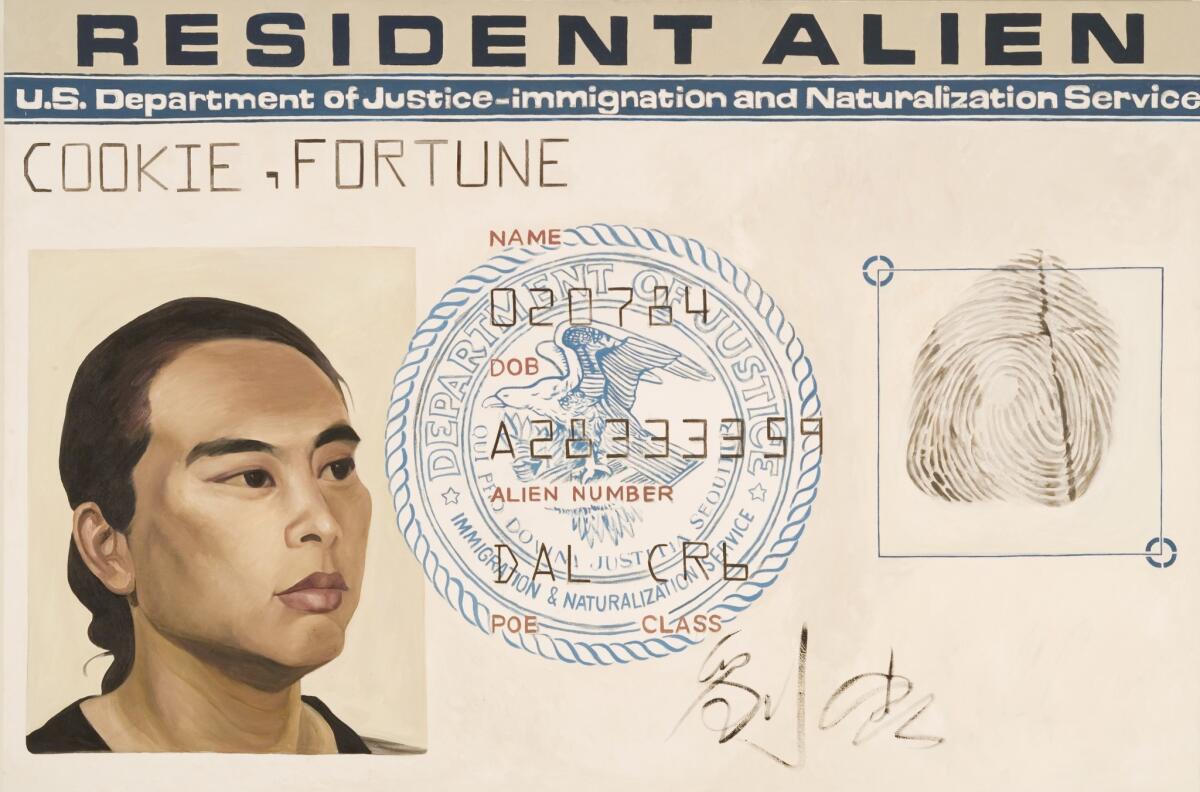

Among them is Hung Liu’s well-known 1988 painting of her U.S. immigration card, subtly fused with a birth announcement that corresponds to the date of the card’s issuance. An immigrant is metaphorically born-again, in a civic rather than religious sense. As self-portraiture about the fluidity of identity, the layers of “Resident Alien” deepen.

Also notable is Sergio de la Torre’s “This Is Not Spanish,” red-neon Chinese characters recalling an ordinary sign for a restaurant or dry-cleaning store, accompanied by three short videos. Backed by the hum of a droning soundtrack, reminiscences of long-ago communal life in a large house in China bump up against images of a Tijuana apartment building and young men and women moving furniture around inside a shop in Tijuana’s primary Chinese Mexican neighborhood. Eventually the furniture piles up against the windows, a barricade against the outside world that also opens a controlled space within.

A wall text at the exhibition entry suggests that the Chinese Exclusion Act was part of the impetus to create a border fence with Mexico in the first place, so that Chinese deportees who fled the U.S. to Latin America would be deterred from returning. That was news to me (although no details or citations are given). “Soul Mining,” if not fully satisfying, is still the kind of show that makes a visitor want to know more.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

‘Soul Mining’

Where: Vincent Price Art Museum, East Los Angeles College, 1301 Avenida Cesar Chavez, Monterey Park

When: Through July 14; closed Sundays and Mondays.

Information: (323) 265-8841, www.vincentpriceartmuseum.org

Twitter: @KnightLAT

MORE ART:

The city of L.A. gave local artists $10,000. See what they did with it

Visual artist and theater company make magic from Virginia Woolf's 'To the Lighthouse'

David Hockney, a portrait of the portrait artist at 80: 'I'm still curious'

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.