Brazil’s modern look: Why Olympic viewers should know the name Roberto Burle Marx

Avenida Atlantica, along Rio de Janeiro’s Copacabana Beach, was redesigned in 1970 by the renowned Brazilian landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx. The patterns run about 2 ½ miles along Copacabana Beach. With the Olympic Games in town, the work of

The Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro have been a showcase more for Brazil’s political and economic anxiety than any kind of architectural drama. None of the venues built for the Games is unorthodox or photogenic enough to rival Herzog & de Meuron’s 2008 Bird’s Nest stadium in Beijing or the swimming and diving center the late Zaha Hadid designed for London four years ago.

But if you look closely enough, even or perhaps especially on TV, you can get a quick education in modern design anyway. The great Brazilian landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx, who died in 1994 at 84, has emerged as a mute and minor star, a compelling bit player, of these Summer Games.

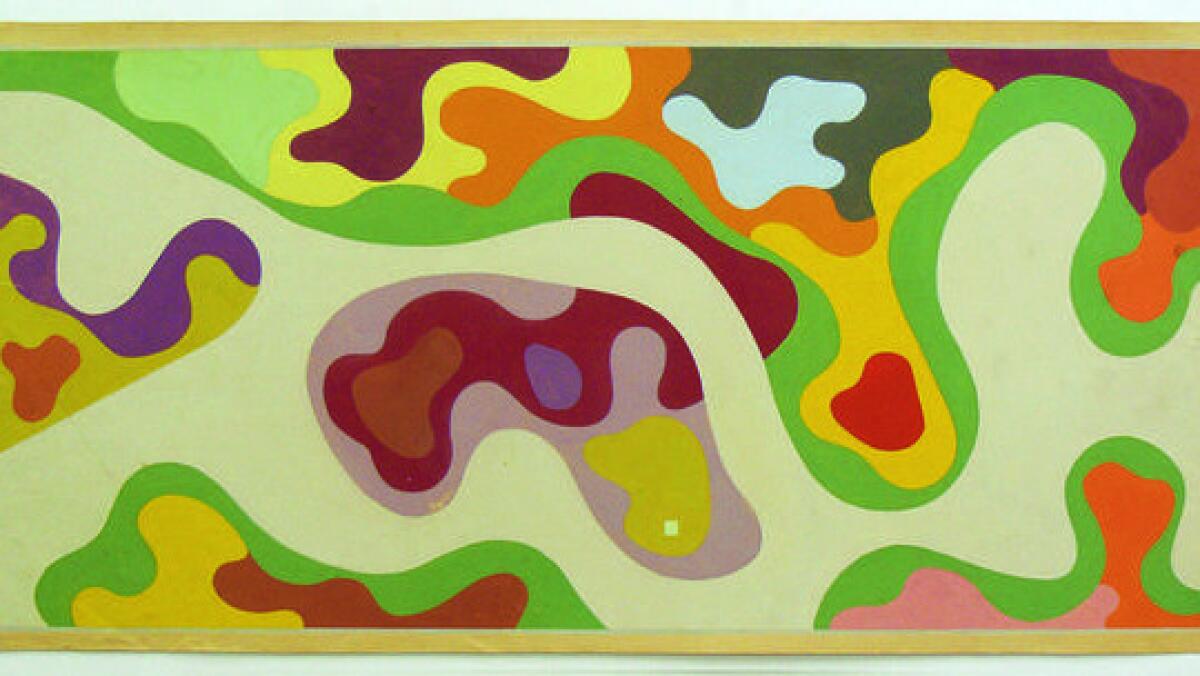

His fluid and brightly colored style — imagine a Southern Hemisphere Jean Arp with a dash of Ellsworth Kelly — has clearly influenced the Games’ official graphic design, which you can glimpse on digital screens behind the swimmers and divers and at other venues.

And his 1970 redesign of the sidewalks and public spaces on Avenida Atlântica, which runs in a wide crescent along Copacabana Beach, has already popped up a number of times on NBC this week. When the cyclists in the women’s road race pedaled from the starting line, they were flanked in the aerial shots by long stretches of Burle Marx-designed pavement.

Anybody familiar with his career, which is the subject of a dense and appealingly wide-ranging exhibition that will run through Sept. 18 at the Jewish Museum in New York before traveling to Rio next year, will not be surprised by this moment in the spotlight. If there were ever a body of work seemingly tailor-made to be captured by blimp, helicopter, hotel balcony or drone and sent out to the rest of the world via TV, computer screen or smartphone, it belongs to Burle Marx.

Born in 1909 in Sao Paolo to a German Jewish father and Brazilian Catholic mother, Burle Marx was trained as a painter. Some of his figurative, Cubism-inflected canvases from the 1930s and ’40s hang near the start of the Jewish Museum exhibition, “Roberto Burle Marx: Brazilian Modernist.” In fact the show reveals that Burle Marx’s gardens turned abstract well before his paintings did.

He began working professionally as a landscape architect while still in his 20s and designed more than 200 gardens in all. In the triumvirate of dyed-in-the-wool modernists who dramatically remade Brazilian cities over the course of the last century, which also included architect Oscar Niemeyer and architect and planner Lucio Costa, Burle Marx’s role was both the most limited and the most clearly defined: He did the gardens and the civic spaces. The green spaces and the plazas.

Yet he was the opposite of a specialist; an amateur baritone and a serious art collector, he threw elaborate dinner parties and designed murals, tapestries and jewelry.

He was also a self-trained botanist who made a point of using native species, rejecting the French symmetry and imported plants common in gardens commissioned by wealthy South Americans at the time. ("He was the creator of Brazilian gardens," Costa said.) He fought a long and public battle to bring attention to the destruction of the Amazon rainforest.

His gardens and public parks — the earliest of them produced nearly a century before Google Earth — seem almost inherently to understand the clarity and drama of the top-down view, along with the ways in which that perspective is exploited more effectively by landscape architecture than any other art form.

The flip side of that obsession is that the gardens appear somewhat less memorable at ground level. And less colorful too: If you put Burle Marx’s gouache-on-paper plan for a rooftop garden at the Ministry of Health and Education in Rio, a 1938 commission that helped make his reputation, next to a photograph of the completed project, the flowing shapes look much the same but the palette has narrowed from a mixture of green, orange, ice-blue, lavender and pink to bands of light and dark green.

This in turn gives the exhibition, curated by Jens Hoffmann and Claudia J. Nahson, an unusual and almost paradoxical jolt of energy. If most shows on architecture and landscape architecture are in a basic sense estranged from their subject matter — you can’t hang a building or a garden on a museum wall — this one is able to walk right up close to its protagonist, whose preliminary sketches and plans for major gardens arguably rank as his most important and fully realized (not to mention most beautiful) work.

What the exhibition most clearly suggests is that if Burle Marx hadn’t come along when he did, Brazil might have had to invent him. The country, vast and quickly growing, was in the 1930s and ’40s trying to absorb the influence of the Modern movement and tailor it to local conditions.

That meant a decades-long push and pull between the sometimes dogmatic rule-making of International Style architecture — flat roofs, clean lines, no ornament — and a culture that prized a more joyful, less bloodless aesthetic.

Enter Burle Marx as an ideal mediator, producing gardens that were both highly disciplined and boldly graphic in their own right but when set against or atop a boxy and all-white modern building couldn’t help but humanize and deepen the effect of the architecture.

That 1938 garden for the Ministry of Health and Education in Rio is perhaps the best known example. The office tower, designed by Costa (with Niemeyer as his assistant and French architect Le Corbusier as consultant), is a typical modern slab, except that a two-story pavilion extends out over the entrance like a dresser drawer pulled all the way open.

On the roof of the pavilion, as a private garden for top officials at the ministry, Burle Marx created a landscape that is a striking distillation of the relationship between the built and the planted — and by extension, as Hoffmann and Nahson put it, “between the rational and the lyrical.”

When Brazil decided in the 1950s to build a new capital, Brasilia, on a remote plateau nearly 600 miles northwest of Rio, Burle Marx took on an even more prominent role in shaping the nation’s modern identity. The slogan of Brazilian President Juscelino Kubitschek about the construction of Brasilia — that work would proceed quickly enough to achieve the progress of “50 years in five” — reflected the pressure, and the unusual appeal, of the project, which was overseen in large part by Costa and Niemeyer.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

Ultimately Burle Marx would receive more than a dozen major commissions in the new capital, including a vast landscaped plaza for the Ministry of the Army and gardens for the American and West German embassies.

He also worked abroad, designing gardens in Venezuela and the pavement along Biscayne Boulevard in Miami. In the late 1940s he collaborated with Niemeyer on a beachfront house and garden in Santa Barbara that was never built. The exhibition includes a model of the project complete with two tiny white boats nosing up to the beach.

Burle Marx didn’t invent the idea of lining the sidewalks along Copacabana Beach with bold pattern — a similar design, based on Portuguese examples, was installed decades before 1970.

But he amplified the style enough — along with nationalizing it, producing new rust-colored patterns in the median that no one would confuse with European precedents — to invent an optimistic and self-contained image of modern Brazil, a sort of logo ready to be transmitted by photographers (and now TV producers and Instagram fanatics) to the rest of the world.

Optimism, of course, is in short supply in contemporary Brazil. That the confidence of Burle Marx’s design for Copacabana is at odds with Brazil’s rather dark current view of its own prospects only adds another layer to the complex story of his life and work.

That new layer and Burle Marx’s star turn in coverage of the Rio Games seem likely to please Hoffmann and Nahson, who write in the show’s catalog that to think of Burle Marx as an artist who “painted with plants,” as an earlier generation of art historians did, is far too simple.

Instead they insist on recognizing not just the multidisciplinary nature but what they call the “unruly legacy” of his work, arguing that however elegant and streamlined his garden plans look to us now “his creative impulse was such that it could not be contained, going beyond artistic constraints and geographic boundaries: beyond Rio, beyond Brazil, and into the world at large.”

Twitter: @HawthorneLAT

ALSO

Why the Rio Olympics opening ceremony matters

How an L.A. designer set the stage for unity at the Democratic convention

Teflon minimalism: The surprisingly sleek architecture of the GOP convention

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.