From the darkness of Vietnam, a Native artist carved out his place. The Autry Museum shows how

Artist Rick Bartow’s mother was white, and his father was a Wiyot Indian. Bartow grew up going to church on Sunday morning and to Native ceremonies in the afternoon. When people asked which culture he identified with, his answer was both.

This duality came to define his art, which is on display at the Autry Museum of the American West in the exhibition “Rick Bartow: Things You Know But Cannot Explain.” The show is the most extensive retrospective of Bartow’s work, and it comes two years after his death from congestive heart failure.

Autry chief curator Amy Scott calls Bartow part of a breakthrough generation of Native artists who pushed “outside of the bounds of expectations and definitions that have been imposed upon it.” Despite that and comparisons with 20th century masters including Francis Bacon, Robert Rauschenberg and Jean-Michel Basquiat, he is not a household name outside of his home state of Oregon.

This show, the ninth stop of an 11-city tour, tries to remedy that, said Bartow’s longtime friend Charles Froelick, who also manages Bartow’s estate.

Institutions specializing in Native art, such as the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., the Heard Museum in Phoenix and the C.N. Gorman Museum at UC Davis, showed Bartow’s work, Froelick said while walking through the Autry exhibit. Other museums, he said, not so much.

That problem, Scott said, is coming to heel as curators and art historians start to consider work by Bartow and others as contemporary art first before moving on to consider the ways that Native identity, traditions and experiences inform the work. That evaluation has often been done in reverse.

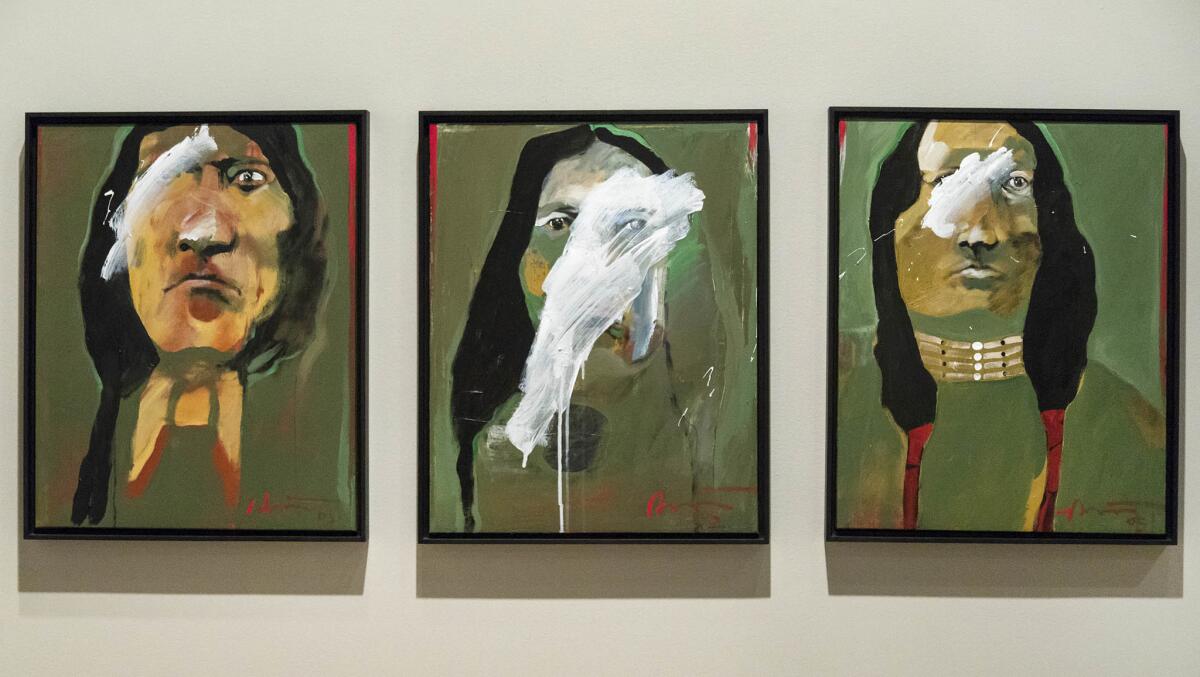

Bartow did indeed identify as a Native artist, and his work is marked by a tendency to upend stubborn stereotypes. In a series of three portraits titled “Bad Ass NDN1, 2 and 3,” Bartow depicts fellow Native artists including Dan Lomahaftewa and Darren Vigil Gray as if from a photograph by American West photographer Edward Curtis, complete with feathers and beaded necklaces.

“They integrate expressionism and contemporary references along with traditional Native imagery in ways that critique our expectations for what Native people, or art, is,” Scott said of the series.

She added that one of the most exciting aspects of contemporary art by Native people in the Bartow and post-Bartow generations is a sense of anger and angst over history and how the artists reconcile those feelings with the rise of social justice movements to call attention to “what colonization meant to Native people instead of romanticizing it as the Manifest Destiny version of American history.”

Bartow had a conflicted relationship with America, despite his deep love of it. He was born in Newport, Ore., in 1946, and his father died of alcohol poisoning when Bartow was 5. Bartow’s mother remarried and tried to help Bartow understand his Native heritage. He studied art at Western Oregon University in Monmouth and was drafted to Vietnam upon graduation.

From 1969 to 1971 he served as a teletype operator and a musician in a military hospital, singing and playing guitar for men as they died. When he returned to Oregon, he suffered from PTSD and lost the 1970s to alcoholism, Froelick said.

Bartow burned his art in those years. The earliest Bartow paintings Froelick has date to 1979, when Bartow finally bottomed out and sought help from a local elder on the Siletz Reservation. That’s when his art-making became as prolific as his written meditations on his practice and its meaning.

Bartow didn’t like to be misunderstood, said Froelick, and when a piece of his work was going into a catalog for a museum and needed contextualizing, Bartow was more than happy to comply.

In a 1989 essay titled “Transformations,” Bartow wrote eloquently about art as salvation:

When I returned from Viet Nam, like so many others, I was a bit twisted. I was a house filled with irrational fears, beliefs, and symbols. Wind-blown paper would send me running; crows became many things; I never remembered dreams and detested the wind; I wore bells on my wrists so I could hear my parts when they moved; I slept in my clothes so I’d be ready to go nowhere at all. And I once recall answering when asked my name and where I was from, Nobody. Nowhere. I must have been a wonderful companion.

During this time I found a huge pad of newsprint and began to draw, trying to exorcise the demons that had made me strange to myself. My work has never stopped being therapy.

Bartow was an intellectual omnivore, Froelick said. He read voraciously and loved biographies — of Vincent Van Gogh, Marc Chagall, Cy Twombly. He adored music, played the blues and religiously wore a Led Zeppelin T-shirt. He had a beautiful voice and sang about love and loss.

He befriended people from all walks of life. He said if you were going to do something in the world, you had better be good at it, even if it was peeling potatoes.

“He was self-deprecating, funny, playful, headstrong and easy to have a conversation with,” Froelick said. “He was really deep, but he didn’t put on airs about his knowledge.”

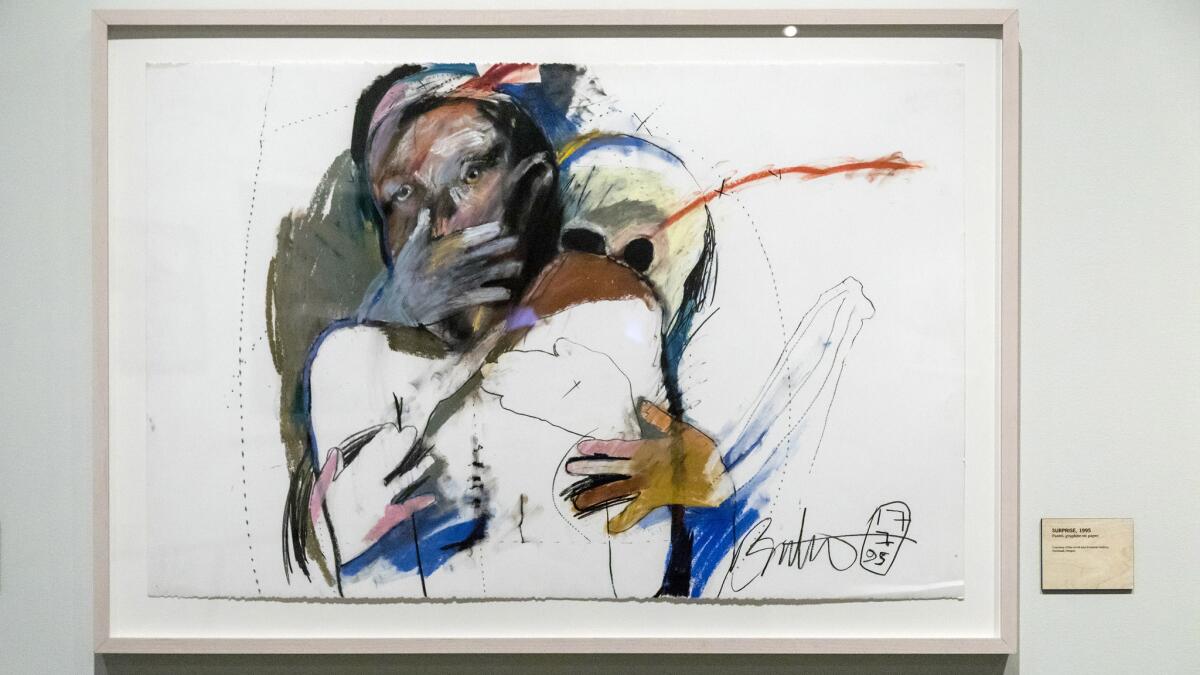

The title of the Autry exhibit is from a 1979 graphite-on-paper drawing of the same name that shows a shadowy figure, its mouth frozen in a scream — right hand clawing out at the viewer. In the background, one can barely make out a second face in the blackness.

Bartow created the work just as he quit drinking and was struggling to make sense of his place in the world and his path as an artist. Multiple faces — sometimes animal and human combined — would come to be a hallmark of his work. He often layered one face on top of the other in homage to the shifting nature of existence.

Despite many painful setbacks in his life, including his wife’s death to breast cancer in 1999, Bartow continued to make art. He suffered a debilitating stroke in 2013 and he could no longer recite the words to his songs or read, but he could still draw. He took a pencil from a nurse in the hospital and drew a bird on a piece of paper. He snapped a picture of the bird and texted it to Froelick.

“He said, ‘It’s gonna be alright because I can draw,’ ” Froelick recalled. “After 2013 he exploded in the studio. He was all pistons firing until he got a pacemaker at the end of 2015, and had his final decline.”

Bartow died in Oregon in 2016.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

‘Rick Bartow: Things You Know But Cannot Explain’

Where: Autry Museum of the American West, 4700 Western Heritage way, L.A.

When: Through Jan. 6, 2019; then moving on to Bend, Ore., and Missoula, Mont.

Admission: Adults $14, students and seniors $10, children $6

Information: (323) 667-2000; www.theautry.org

Twitter: @villarrealy

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.