The musical minds behind ‘Serial,’ ‘S-Town’ and ‘Radiolab’ push a new art form: the podcast score

If you were among the 175 million people who downloaded “Serial,” the true-crime podcast phenomenon that went on to win a Peabody Award, the plinking piano chords in its theme song are probably still ringing in your head — musical glue that helped bond the riveting murder mystery.

“I just knocked it out in a weekend,” said composer Nick Thorburn, an indie rocker from British Columbia, Canada. “I didn’t think much of it.”

Thorburn may not have overthought it, but his composition soaked into pop culture the way a recognizable TV theme or hit song might. As podcasts grow in popularity and ambition, they’re proving an exciting laboratory for original music, essentially creating a new art form: the podcast score.

Thorburn’s role was similar to a film or TV composer in that he helped set the mood for a piece of entertainment. But in process, “Serial” was much more in keeping with the traditions of non-fiction radio programs such as “This American Life,” where freelance composers write a bank of tracks — not for any specific moments, and sometimes not even knowing the subject matter. The producers then chop up and place those pieces at will, essentially co-scoring the show.

It’s a blank canvas, said Matt McGinley, another composer who writes music for “This American Life” — although there is a kind of house template.

“A piece of music should be around two minutes long, and it should have a clearly defined beginning and a clearly defined ending,” he said. “It should have at least one musical variation. It’s great if it can have a rise of some sort within the song. Other than that, you have a lot of freedom.”

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

When McGinley wrote music for “S-Town,” the popular follow-up to “Serial” about the residents of a town in Alabama, he knew more about the content and characters than he ever does for “This American Life.” He wrote a Southern-flavored track and an organ funeral hymn, knowing that a character dies, but was still basically handing over a batch of what’s known as “library” or stock music.

Untethered by the jumpy contours of a narrative, writing music for podcasts becomes more like songwriting, according to Andrew Dost, composer for “Missing Richard Simmons.” Dost wrote his tracks (which favor handclaps, vocals and acoustic instruments), inspired by the premise — the eccentric fitness guru dropping off of the public radar — and a handful of moods outlined by the producers.

“If I’m doing a TV show,” said Dost, “sometimes it’s only a five-second cue, and you want to hit this beat, you want this to happen, and then you want to get out of there. With a podcast, you want to take people on a little two-minute journey, or sometimes it’s 30 seconds — but it’s a little more song-like, and maybe even a little more freeing than a song, because you can take a breath and wait for a minute. The actual composition can dictate the length of that pause.”

Podcasts are simultaneously one of the newest storytelling forms, and a very old one — tracing their lineage to the early days of radio. Jad Abumrad, creator and co-host of the popular WNYC radio show and podcast “Radiolab,” was taken to the station’s archives when he first started, full of records of music for old-time radio dramas.

If that was a show on TV, I’d have bought a house by now, based on the royalties. But that’s how it goes.

— Podcasts composer Nick Thorburn

“You had these huge records with these little 30-second stings,” he said, “and they would be labeled, like, ‘Romantic,’ ‘Day-Tripping,’ ‘Industry’ — and each one captured a certain kind of mood. Early ‘Radiolab’ is just riddled with that old incidental music that I would warp and tweak. It is funny, thinking of [podcast scoring] as a kind of return to the beginning.”

Abumrad studied composition at Oberlin College, and when he landed as the host of his own show, it was all about musically experimenting with the public radio format — treating words like musical objects and applying 12-tone composition techniques.

Abumrad was one of the first podcasters to start using original score. Early on, he was playing with mostly existing music by bands and composers — standard practice for public radio, which has long enjoyed a cozy arrangement with performance rights organizations to use whatever music they want, carte blanche.

“But as you got into podcasting, where it hangs around and it’s not just broadcast, the rights issue shifts on you,” he said. (If a podcast gets downloaded 175 million times — or even 10 times — and uses unlicensed music, that spells legal and ethical trouble.) “We were like, ‘OK, this just has to be part of our creative process now: We write the music.’ And now we write all of it.”

“Serial” was a blockbuster — but unlike movie blockbusters, there’s not much money in podcasting, at least not yet. Composers are typically paid a one-time, non-exclusive fee for their tracks, with no residuals. (No one interviewed for this story wanted to give a dollar amount, but one composer said the rates he’s received are fairly comparable to indie film projects.)

“If that was a show on TV, I’d have bought a house by now, based on the royalties,” said Thorburn. “But that’s how it goes.”

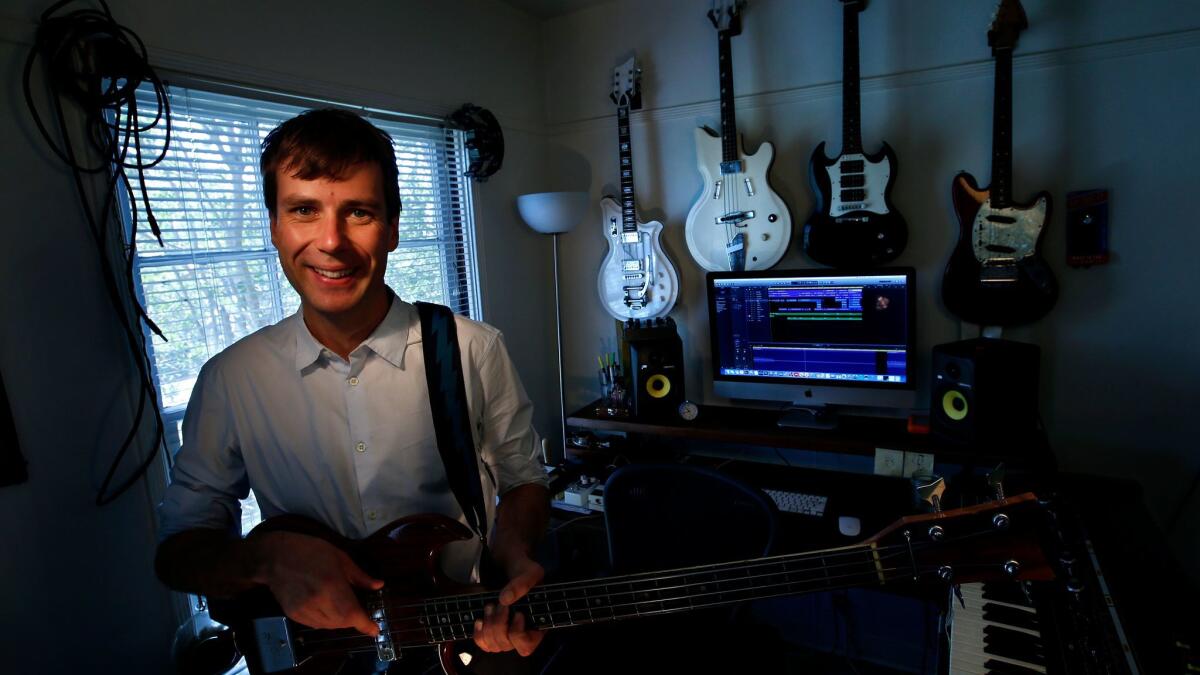

Small budgets also necessitate that composers be one-man-bands, either using sampled instruments or performing everything themselves — which means it’s unlikely a podcast score will ever be performed by an 80-piece orchestra. Scores typically have more intimate, acoustic palettes, which is often the right fit for the medium anyway.

“You want it to sound sometimes like a dude in his bedroom, and other times you want it to sound like maybe a string quartet,” said Mark Phillips, a former public radio producer who contributed additional music to “Serial.” “It’s all about matching the scale of the story and the production.”

Podcast creators are beginning to experiment with non-journalistic genres like dramatic narrative, which opens up a new world for scoring. Phillips recently scored the psychological thriller “Homecoming,” which featured film stars Oscar Isaac and Catherine Keener. He opted for a spare approach to match the verité style of the story, but can see himself writing more “cinematic” scores for future shows.

“If it’s an integrated process where you’re thinking about the scoring during the writing and conception, I think it can work,” he said. “But if you write a screenplay and record it, and then just score it [like a film], I think the risk of it sounding cheesy is way higher — if it’s this afterthought. Because it is so challenging to have music that really works in an audio-only story. It’s like a baby genre, and no one’s really even scratched the surface of how to do it best.”

Support coverage of the arts. Share this article.

MORE ARTS:

How the ‘Hamilton’ silhouette came to be the show’s iconic image

Disneyland meets Hogwarts at $700-million USC Village

Sterling K. Brown, Darren Criss and others to perform ‘In the Cosmos’

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.