Review: Avant-garde and self-taught artists intersect at LACMA’s ‘Outliers and American Vanguard Art’

“Outliers and American Vanguard Art” is a big, unruly traveling exhibition with lots of terrific paintings, sculptures, drawings and photographs to see among its more than 250 assembled works. They span the 20th century, nudging into the 21st.

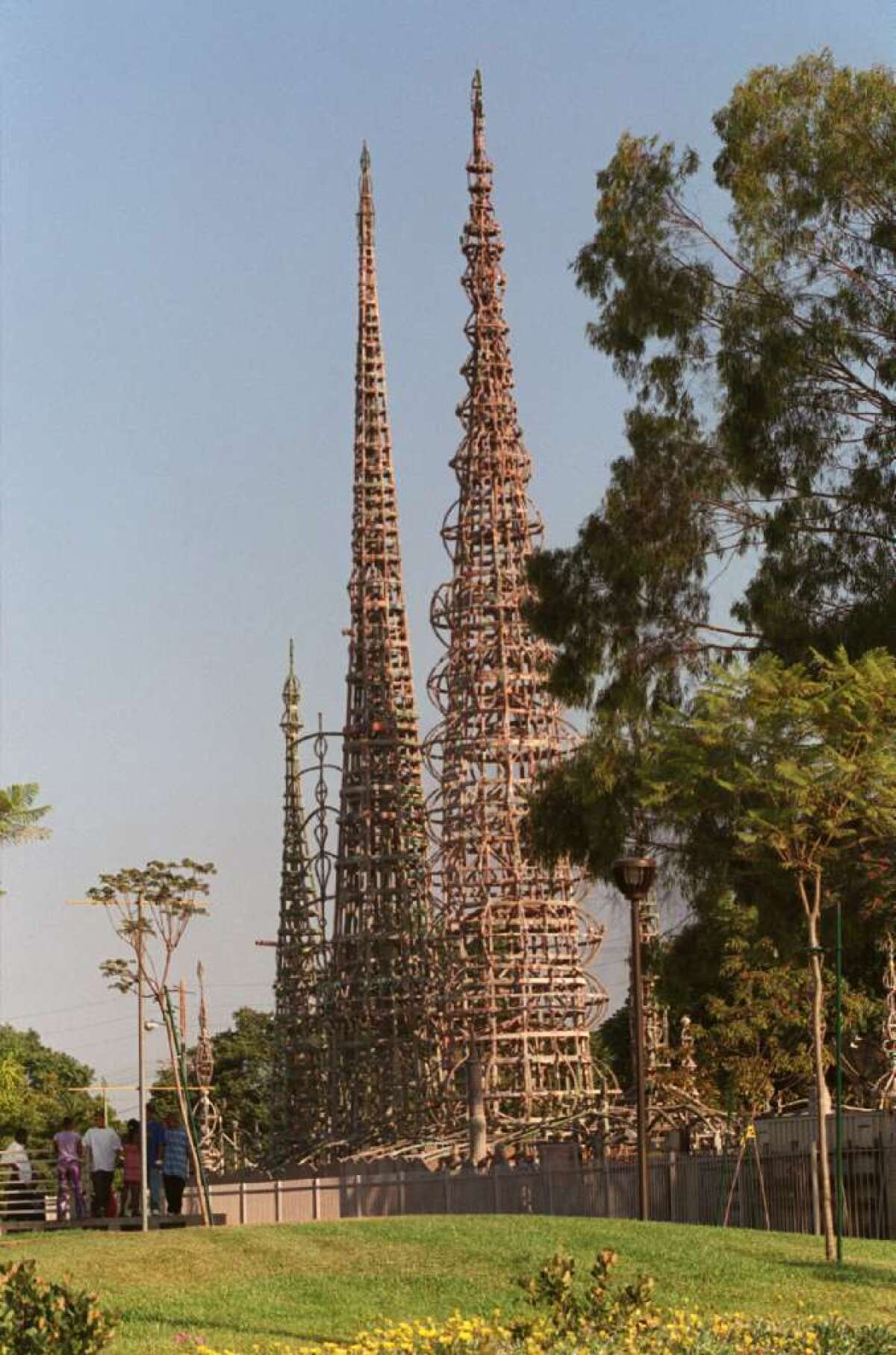

The show, newly opened at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, considers moments when the Modern art establishment turned to outliers for inspiration. “Outlier” is a current term for those variously known in the past as folk, primitive, visionary, naive and outsider artists. Simon Rodia (1879-1965), a working-class immigrant and creator of the monumental, filigreed concrete towers encrusted with broken crockery, sea shells and bottles on East 107th Street in Watts, is the nation’s premier modern example.

From folk through outlier, the shifting terminology speaks of a certain unease with which these artists’ work is often approached. A sincere and deeply felt admiration is mixed with discomfort over just how to approach often remarkable art made by mostly untrained men and women, who do what they do outside the established art world structure. Outliers make art beyond institutional boundaries because they are indifferent to — or have been ostracized from — the prevailing social system. So, we shouldn’t be surprised when institutional efforts to corral their work feel bumptious and disorderly.

The show insightfully identifies three general periods of American history where outlier artists came to considerable institutional attention, and it is installed accordingly: first, deep into the Great Depression of the 1930s; then, during the 1970s backlash to successes in the various civil rights and anti-war movements; and, most recently, following the 9/11 terrorist attack on the United States.

For me, what these three moments share is an often inchoate yet penetrating awareness of profound establishment failure. In its wake, outliers suddenly began to look like an alternative. The problem is that those are reactionary aesthetics — a backhanded sop for artists of exceptional talent, however unschooled. Institutional respect shouldn’t depend on contrition.

“Outliers and American Vanguard Art,” organized by the National Gallery of Art, smartly approaches the subject from multiple angles.

Sometimes an artist draws critical inspiration, as in “Sidewalk Drawings,” a shrewd painting by Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000). As children do, two energetic young girls wielding chalk have scrawled a rudimentary battleship, flags, a bomber, two slugging boxers and other images across city pavement. An aerial view, the flattened sidewalk is coterminous with the flat paper on which Lawrence painted, filling it edge to edge.

Here the outliers are children, esteemed by Jean Dubuffet and other Modern artists as a font of primal creativity. The 1943 scene melds a topical inventory of wartime images with Surrealism’s fascination for children’s art, uncorrupted and without adult prejudice, which the deft composition embraces. Lawrence, then just 26, loosely identifies himself with those creative, all-American kids.

The painting’s drawing of battling boxers likely refers to Joe Louis, the lionized Brown Bomber and reigning heavyweight champ, and Germany’s Max Schmeling, handily defeated by Lewis. In the process, “Sidewalk Drawings” pokes a wry finger into the art establishment’s eye: The so-called “primitive” art of Africa was instrumental in the revolution of Modernist abstraction, which Lawrence embeds within his vision of the radical alternative of children’s art.

Lawrence is a good example of how discombobulating the outlier label can be in a show like this. (The picture graces the cover of the fat and generally fine catalog.) As an academically trained African American artist working under the heel of a Jim Crow society, the painter was himself a different kind of cultural outlier. Today he is universally recognized as a leading Modern artist, which puts him squarely in the establishment pantheon.

Something similar describes other artists in the show, all of them very different from one another.

William Traylor (1853-1949), an Alabama sharecropper born a slave, didn’t begin to make his preternaturally beautiful silhouette drawings on scraps of cardboard until he was 85. Marsden Hartley (1877-1943), abandoned by his family for a year during childhood, got scholarships to art schools, traveled widely in Europe, showed at Alfred Stieglitz’s influential New York gallery and made brash portraits of the men he loved, personally and intellectually.

Hartley recalls John Kane (1860-1934), an immigrant Pennsylvania miner and railroad worker, whose muscular self-portrait is as iconic a representation of rough masculinity as Hartley’s tender depiction of “Adelard the Drowned, Master of the ‘Phantom,’ ” a friend and Nova Scotia fisherman who died at sea, shown with a rose lovingly tucked behind his ear. Kane, an alcoholic drifter whose work was advocated by American Cubist painter Andrew Dasburg, saw his work collected by prominent museums, while the culturally refined Hartley exiled himself from the mainstream of American art, first to Berlin and then to his native Maine.

During her downtime as a practical nurse, reclusive Rosie Lee Tompkins (1936-2006), born Effie Mae Martin, sewed stunning, improvisational quilts that fuse organic form with vivid, patterned geometry to create abstract narratives of individual devotion. An exquisite wooden box, laboriously handcrafted from inlaid walnut by sculptor H.C. Westermann (1922-1981), master of Dada wit, opens to reveal — what else? — a cache of common walnuts, held as a splendid treasure, like holy relics in a magnificent reliquary.

The show also considers the institutional influence of museums on outlier artists and our consideration of them. They include familiar shows such as “Naives and Visionaries” at Minneapolis’ Walker Art Center in 1974; “Black Folk Art in America: 1930-1980” at Washington, D.C.’s, Corcoran Gallery of Art in 1982 (it traveled to Los Angeles); “Parallel Visions: Modern Artists and Outsider Art,” organized by LACMA in 1992 (and closest thematically to “Outliers and American Vanguard Art”); and “Soul Stirring: African American Self-Taught Artists from the South” at the California African American Museum five years ago. Artists shown in all of them are included here.

However, special mention goes to the influential Museum of Modern Art, where founding director Alfred Barr repeatedly insisted that Modernism could not be understood without what was then generally called “primitive art.”

In a show about the American vanguard, it’s a surprise to see French painter Henri Rousseau’s serene and luxuriant “Tropical Forest with Monkeys,” a 1910 fantasy of jungle wildlife that he manufactured from visits to a tame Parisian zoo and botanical garden. The splendid canvas, a type admired by MoMA stalwarts Picasso and Matisse, is installed near a classic “Peaceable Kingdom” showing Edenic animals living in harmony with indigenous Indians by Edward Hicks (1780-1849), the Pennsylvania Quaker minister and self-taught artist also vigorously championed by Barr in the museum’s early years.

Ironically, the focus on museums and their influence on the reception of outlier artists conjures a problem that hampered LACMA’s 1992 “Parallel Visions.” In an era like ours, when art schools are prominent, both shows champion unschooled art. Yet, the self-taught are admired for their varied impact on establishment thinking, not only for their abundant intrinsic merits.

The fate of the vanguard gets the emphasis. In “Outliers and American Vanguard Art,” the effect of the former on the latter is the focus. A stubborn hierarchy remains, with the schooled and the unschooled not quite yet on equal footing.

LACMA, 5905 Wilshire Blvd., (323) 857-6000, through March 17. Closed Wednesday. www.lacma.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.