A photographer’s remarkable, bittersweet diary of his daughter’s life, MRI and all

Leon Borensztein’s photographic chronicle of his daughter, Sharon, begins at the beginning, with her birth in 1984. We see the dark, sticky hair on her crowning head. We see her fresh little form carefully cupped in adult hands, dipped in the silvery waters of a sink bath.

Before long, we also see the tiny, bundled baby sliding into the tunnel of an MRI machine. And we see her, slightly older, eyes wide with primal alarm, forehead daubed with gel, as an ultrasound probe is held to her temple like a divining rod. Sharon has been diagnosed with multiple disorders; she is legally blind, obsessive compulsive and on the autism spectrum, and she has seizures.

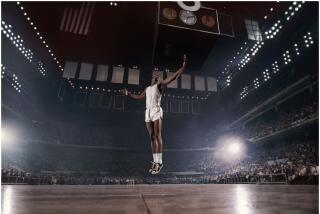

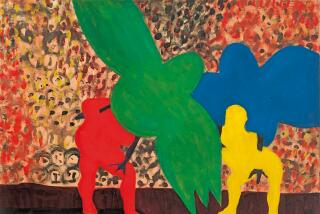

Borensztein’s piercing show at the Little Big Man Gallery includes more than 500 black-and-white pictures — large and small, framed and not, in isolation and in sweeping sequences, augmented by Sharon’s own drawings. Hundreds more photographs could be added with no risk of dilution, so absorbing is this familial portrait and so acute Borensztein’s perspective.

The linear narrative established just inside the gallery door soon splinters, and images from different periods in Sharon’s life begin to commingle, the installation vividly but light-handedly invoking her own idiosyncratic development, which has caused her to be, in many respects, out of sync with her chronological age.

Borensztein shoots Sharon at rest, at play, at therapy, in fear and joy and countless emotional shades in between. Head down, she scoots a walker across an ice rink. She smiles ebulliently before her birthday cake. She holds a baby tooth in the palm of her hand. She dances. She’s back in the hospital. She is, in what verges on a kind of spirit photograph, a teenager on the beach, at night, haloed by hovering sea gulls.

Among the most moving images are those that read emblematically, where Sharon is not physically present. In one, Borensztein photographs her white cane leaning against a wall where a dress hangs. Both are atilt and in raking light. The cane’s tip disappears into the darkness at the bottom of the print, surrogate eyes in a shadowy world.

Borensztein, based in the Bay Area and a distinguished documentary and portrait photographer, appears in some of the pictures and is implicitly present in all. In a poignant group of shots made for a family new year’s card (signed “Leon, Sharon, Sad Dog”), his stand-in is a camera on a tripod. Sharon, a young woman here, glows in a white dress in the center beside a lumpy, oversized stuffed animal.

In another series, his is the hand holding a photograph of his small daughter up against the glowing sky, or above ribboning railroad tracks or in front of a house — each image a metaphor for Borensztein’s responsibility for this other life, to represent it and protect it. In 2004, Borensztein was awarded full custody of Sharon — or as one publication reporting on the 2016 book version of the project said in a typo packed with truth, he was named her “soul guardian.”

Borensztein’s work is an intimate epic. However contradictory that term seems, it justly clings to the tremendous project, announcing the work’s private scale and immense scope.

Other photographers have documented their families with toughened tenderness — Sally Mann foremost among them. Borensztein’s work stands apart for the particularity of the world Sharon occupies, a world remote to most of us. He records her life as a diarist and explorer, navigating perennially new terrain and mapping the singularity of their experience. His work is a bittersweet testament, an act of fierce love, of empathy doubling as advocacy. He brings us as close as pictures can, right up to the edge of knowing.

Little Big Man Gallery, 1427 E. 4th St., Los Angeles. Through Aug. 25; closed Sundays-Wednesdays. (917) 361-5039, littlebigmangallery.com

See all of our latest arts news and reviews at latimes.com/arts.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.