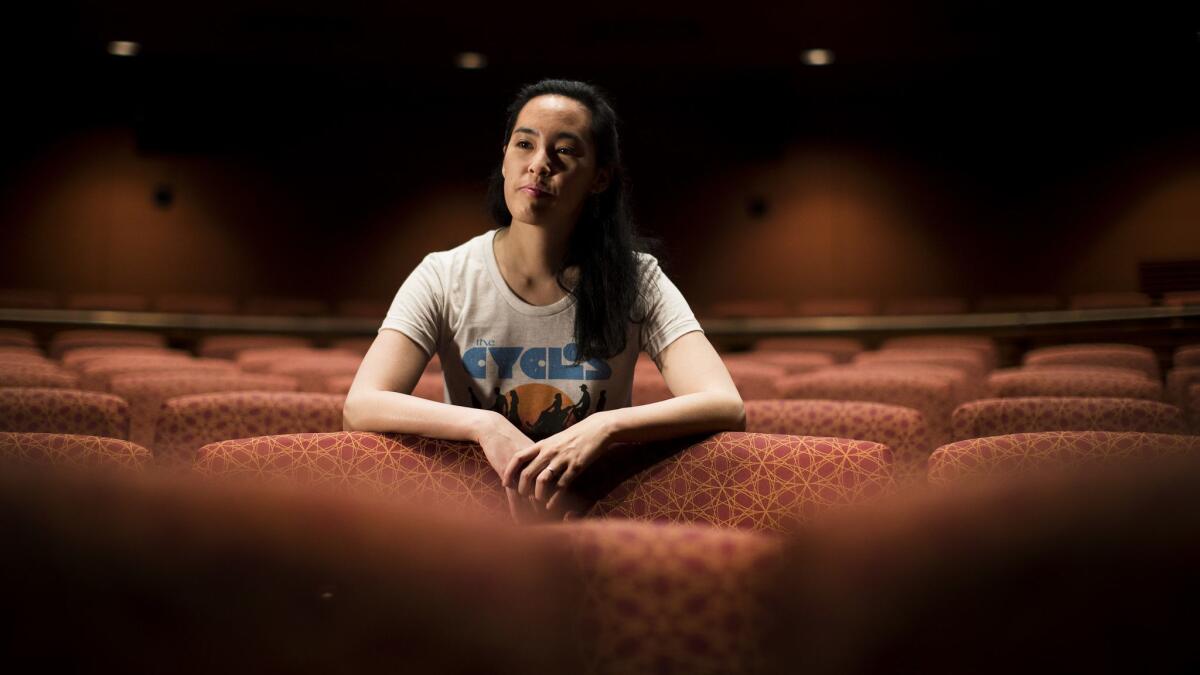

Lauren Yee, playwright on the verge

A real moment of dread came early in the rehearsals for “Cambodian Rock Band.” In Lauren Yee’s new play, a musician trapped in a country ripped apart by revolution and genocide announces from the stage: “They’ve taken over the airport. No one’s getting out!”

The actor who utters those lines, Joe Ngo, 33, recalled how his mother — a survivor of the Khmer Rouge’s short but horrific reign in Cambodia, and also the play’s language consultant — panicked.

“After we did that scene, she told me, ‘I remember that day. We were just kids,’” Ngo said.

“Cambodian Rock Band,” running through this weekend at South Coast Repertory, is a richly layered exploration of that tortuous time, earning accolades from Times reviewer Margaret Gray as a “fierce, gorgeous, heartwarming, comedic fairy tale set against one of history’s grisliest mass extinctions.”

The play is Yee’s first with live music and another step in the evolution of the fast-emerging playwright, whose Asian heritage is central to her work and whose rise comes at a time when theaters are pushing for more inclusion in both casting and the stories being told.

Yee wrote her first play at 15 as part of a competition for the Asian American Theater Company. She studied English and theater at Yale and UC San Diego. Her work is often family-focused and sometimes provocative (hence her 2008 title “Ching Chong Chinaman”), mingling drama and “sideways” comedy.

Last year at the Kirk Douglas in Culver City, the Center Theatre Group mounted her autobiographical “King of the Yees,” another family drama-comedy, this one centered on her father and the fading of Chinatowns.

Yee’s play “The Great Leap” just closed in Denver. “Cambodian Rock Band” is set to open next year at the Victory Gardens Theater in Chicago.

For me as an artist, the idea that music and art can be so powerful that a regime goes after you is a really startling idea.

— Lauren Yee, the writer of “Cambodian Rock Band”

As the play’s title suggests, Yee’s way into Cambodian culture was through music. A Chinese American who grew up in San Francisco, Yee said she wasn’t especially knowledgeable about Cambodia, its music or its tragic history when a friend took her to see the band Dengue Fever eight years ago.

Yee instantly fell for the Los Angeles band’s playful mix of Cambodian pop and American surf rock from the 1960s and early ’70s. She became obsessed with the sound and its country of origin.

“Before Cambodia got involved in Vietnam, the country was an incredibly optimistic, forward-thinking nation in which the songs were all these bubblegum love songs,” Yee said. “There was this innocence that the war and the Khmer Rouge regime robbed from Cambodia.”

In “Cambodian Rock Band,” she tells the story of a musician, Chum (Ngo), who survives the genocide and lands in America, sharing little of the horror he’s seen. When his adult daughter travels to Cambodia as part of an effort to prosecute a man who ran a notorious Khmer Rouge prison, Chum follows her there, and previously unspoken history finally unfolds between them.

“I gravitate towards family stories,” Yee said. “There is something that all of us go through when we meet our parents as adults. We think we know our parents, but how much do we really know them and what their lives were like before they had kids? This play is another way of exploring that story.”

Musicians were among the artists, intellectuals, professionals and others targeted for death by the Khmer Rouge, in part for being associated with Western culture. Nearly 2 million are estimated to have been killed by execution and starvation at the end of the 1970s.

“For me as an artist, the idea that music and art can be so powerful that a regime goes after you is a really startling idea,” Yee said. “It makes me wonder what the world lost when the Khmer Rouge went after all those artists.”

In 2015, she began developing what became “Cambodian Rock Band” through a commission from the South Coast Rep’s CrossRoads initiative, which calls for playwrights to engage with diverse local communities. The company invited Yee to Orange County, and she met with members of Dengue Fever at the annual Cambodian Music Festival in nearby Long Beach. The band got involved with the play, and several Dengue Fever songs are included in the final production.

Yee brought an early draft of the play to a workshop with Ngo, who had appeared in one of her earlier plays. His reaction surprised her.

“After I read the first draft of it, I told her this is my family’s story, and my parents are survivors of the Khmer Rouge,” Ngo said.

He told Yee that his parents were teenagers during those years, and they were put to work in camps. His father worked building (and rebuilding) local dams, and his mother planted rice.

Ngo had never talked about his heritage before with Yee. The actor grew up in Monterey Park, and like many others of Cambodian and Vietnamese heritage around him, Ngo had little knowledge of his family background. He developed what he called a “healthy or unhealthy detachment to that history.”

In his 20s, he started to look closer and began understanding why he had never known some relatives in old family photographs.

“I sat down and started reading about it and looked into the numbers,” he said. “My aunt told me when she was a little girl, a Khmer Rouge soldier spared her life. My mom told a story of watching a little boy get killed right in the middle of their camp.”

Ngo took in that history and now plays Chum at ages 18, 21 and 51, helping to spread the kinds of stories that audiences may not have truly absorbed before. He points to last year’s “First They Killed My Father,” a feature film directed by Angelina Jolie, as a positive sign that Cambodian stories are being more widely heard.

“‘It’s more relevant than ever to tell this story because of where we are in our political climate,” Ngo said. “It’s a real sharp reminder of what happens when you have paranoia in government.”

Yee said she’s glad to be not only telling an Asian story of profound meaning but also showcasing Asian American talent, though that’s only one aspect of representation.

“What I stand for as an artist is making sure you’re hiring great Asian American talent,” she said, “not only for plays like ‘Cambodian Rock Band,’ but also for your Shakespeare and your classics and your shows that have nothing to do with cultural identity.”

She said for inspiration she turns to universal family dynamics and true stories — Ngo’s parents among them.

“His mother is one of the sunniest, most joyful people around,” she said affectionately. “It’s a reminder that people deal with trauma in all sorts of ways, and sometimes joy is a survival strategy. It almost seems like his mother has compensated for this incredibly dark time in her country’s history by being a beacon of joy and light.”

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

‘Cambodian Rock Band’

Where: South Coast Repertory, 655 Town Center Drive, Costa Mesa

When: 7:45 p.m. Tuesday-Friday, 2 and 7:45 p.m. Saturday, 2 p.m. Sunday. Ends March 25

Tickets: $30-$83 (subject to change)

Information: (714) 708-5555 and scr.org

Running time: 2 hours, 20 minutes (including one intermission)

See all of our latest arts news and reviews at latimes.com/arts.

ALSO

‘Sell/Buy/Date,’ an exploration of the sex industry, is a one-woman marvel

The 99-Seat Beat: Are we ready for some plays about moral responsibility?

Why is a Shakespeare specialist directing the musical ‘Frozen’?

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.