Review: L.A. Phil’s 100th anniversary gala spreads good vibrations — and visuals — with Coldplay’s Chris Martin and artist Refik Anadol

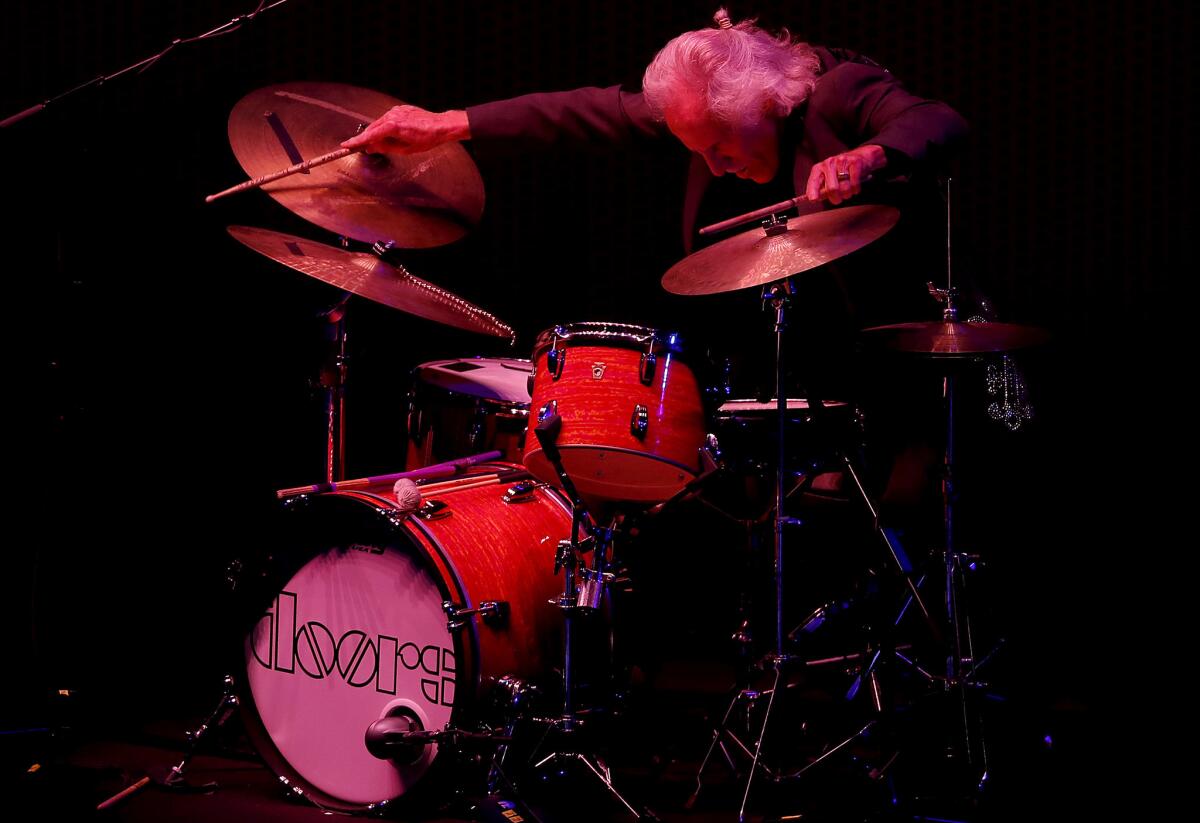

The L.A. Phil’s opening night gala ended Thursday with the audience — including city, county, corporate and entertainment bigwigs — standing, singing and clapping along to the Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations,” the words projected overhead, presumably for the out-of-towners. Gustavo Dudamel conducted the Los Angeles Philharmonic and Master Chorale along with Coldplay’s Chris Martin, esteemed Doors drummer John Densmore, brilliant electric violinist Tracy Silverman and R&B star Corinne Bailey Rae.

Or maybe the “California Soul”-themed gala, and kickoff for the orchestra’s extravagant centennial season, ended after that, when shimmering blue surfboard-shaped confetti rained from the ceiling.

No, it ended an hour later outdoors with the exterior Disney Hall steel alight with video imagery — as its architect Frank Gehry had always intended — and looking, for a spectacular 15 minutes of fame, like the most amazing building in the world.

No, it ended the next morning far away across the pond, with snarky comments on the widely read London classical music blog, Slipped Disc, that decried the pop culture depths to which a great orchestra, which once opened its seasons with the likes of Rachmaninoff, Stravinsky and Rubinstein, had now sunk under our surfboard-besmirched beaches.

(Actually, the L.A. Phil never ever opened its season with galas featuring any of these Russian and Polish émigrés on stage. In fact, the orchestra didn’t have galas in those days like this one to raise millions of dollars for the institution’s extensive education and outreach programs.)

“California Soul” was, to be sure, a mixed bag of things that worked and that didn’t. Before the surfboard drop, Dudamel told the audience, “We don’t have borders in art,” to which Densmore responded with a drumroll of acclamation and the crowd applauded.

It wasn’t just pop music outsiders who were welcomed into orchestra-land; good vibratory activity from visual arts and theater also added to the atmosphere. Ben Zamora designed a light sculpture of crosshatched neon that covered the Disney organ pipes and offered bright lights in seeming conflict with lighting designer Mikki Kunttu’s more subtle color fields on stage.

Directed by Elkhanah Pulitzer, actors Shalita Grant — formerly of “NCIS: New Orleans” — and Bernard White introduced the music numbers with California poetry, not that Beat poetry intoned in an artificial Broadway manner cuts it.

The pieces themselves that Dudamel conducted may not have exactly defined the border-defying California sound, let alone soul — not much, for instance, to represent the epic California contribution to ultimate breaking down of world music borders — but you knew from the start where you were, with the noirish sound of Jerry Goldsmith’s “Love Theme” from the film “Chinatown.”

John Adams, the orchestra’s creative chair, was the featured composer. Had the L.A. Phil and the Master Chorale made the “Wild Nights” finale from “Harmonium” any wilder, it might have meant trouble. The second part from Adams’ violin concerto, “The Dharma at Big Sur” — written for Silverman and the opening of Disney Hall in 2003, an homage to quintessential Californian Terry Riley — came alive as never before.

The first new work of the more than 50 commissioned by the L.A. Phil for its centennial, Julia Adolphe’s “Underneath the Sheen” was meant as a nine-minute atmospheric immersion into a redwood forest. Whether quiet or loud, the trees could be sensed if you knew they were there; otherwise it was an exercise in good, if vague, orchestral vibrations.

The L.A. Phil played Gershwin in the 1930s when other orchestras looked down their noses at him. The same was true when it collaborated with Frank Zappa in the 1970s. By now, however, Zappa’s “G-Spot Tornado,” thought all but unplayable, is almost commonplace in the classical music world.

It opens the Long Beach Symphony season Saturday. As I type, an Italian radio station is streaming it live from a concert opening the venerable Venice Biennale Musica. On Sunday Medici.tv will stream a new production of Zappa’s “200 Motels,” the theater work the L.A. Phil commissioned.

In fact, if there was a problem with Dudamel’s sprightly performance of “G-Spot” in Ali N. Askin’s instrumental transcription, it was that the L.A. Phil made it sound too easy, too orchestra-friendly, too lovable.

That was also the character of David Campbell’s lush orchestral arrangements of the pop songs. With André Previn’s “You’re Gonna Hear From Me” — a sweet tribute to a former music director despite his attempts to put his Hollywood career behind him — one missed Previn’s own luminous use of orchestration. Rae’s soulful singing style, impressive on its own, proved the wrong soul, overstating an eloquently understated songwriter. But the Motown hit “California Soul” could take anything she and the Master Chorale could throw at it.

For his part, Martin brought a stirring intensity to Jim Morrison’s “L.A. Woman” (how could he not, with Densmore’s subdued authority on the drums) and a moving quietude to the ballad “Los Angeles Be Kind,” a song by Scott Hutchinson, from Scottish indie rock group Frightened Rabbit, who passed away earlier this year.

And then there were artist Refik Anadol’s computer graphics projected on Disney.

The 15-minute “performance” with music will be on nightly through Oct. 6, shown on the half-hour, for all to see.

A zillion gigabytes of data and a panoply of artificial intelligence algorithms don’t art make. Much of this is pure hokum. The electronic soundtrack, bits of Stravinsky and this-and-that in fashionable distortion, is the one thing of the evening that should properly embarrass an orchestra on a commissioning spree.

And yet don’t, under any circumstances, miss it.

Anadol or his computer (it’s hard to know who’s in charge) may make a mess of archival L.A. Phil imagery. But no matter, you can’t take your eyes off it. Properly lighted for the first time, the building looks amazing,

And in the moments when we see giant images of Zubin Mehta, Previn, Esa-Pekka Salonen and Dudamel conducting, when we see the orchestra at its business, gloriously covering the hall, the excitement is palpable.

This is what Gehry had intended all along, projecting night concerts as they are happening on the building, and nothing on the Las Vegas Strip or in Tokyo’s neon-arresting Shinjuku district compares.

There has never been any reasonable excuse for city, the county or the Music Center not to embrace Gehry’s vision. After seeing Anadol’s lighting, to not do so now would be to invite bad, instead of good, vibrations.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.