Auction battles and encounters with royalty: LACMA curator looks back at 24 years of adventures

Some people say there are no high-quality Old Master artworks for museums to buy anymore. Curator J. Patrice Marandel said those people are wrong.

“There are fabulous things on the market,” Marandel said. “What you need is money.”

Marandel should know. He retired Friday as chief curator of European painting and sculpture at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, ending a 24-year career there. In the weeks leading up to his final day, Marandel talked with The Times about the hundreds of works he has added to the museum’s collection — the favorite pieces that visitors might see in the galleries, and all the necessary sleuthing, schmoozing and deal-making that came along the way.

He spoke of the characters he encountered at art fairs and auctions, and the suitors who pursued him in letters and phone calls at the rate of five to 10 a day.

“People can be odious, people can be charming, and people can be a bit of both,” Marandel said. “But working in that world amuses me endlessly. I just find it very funny.”

And very stressful.

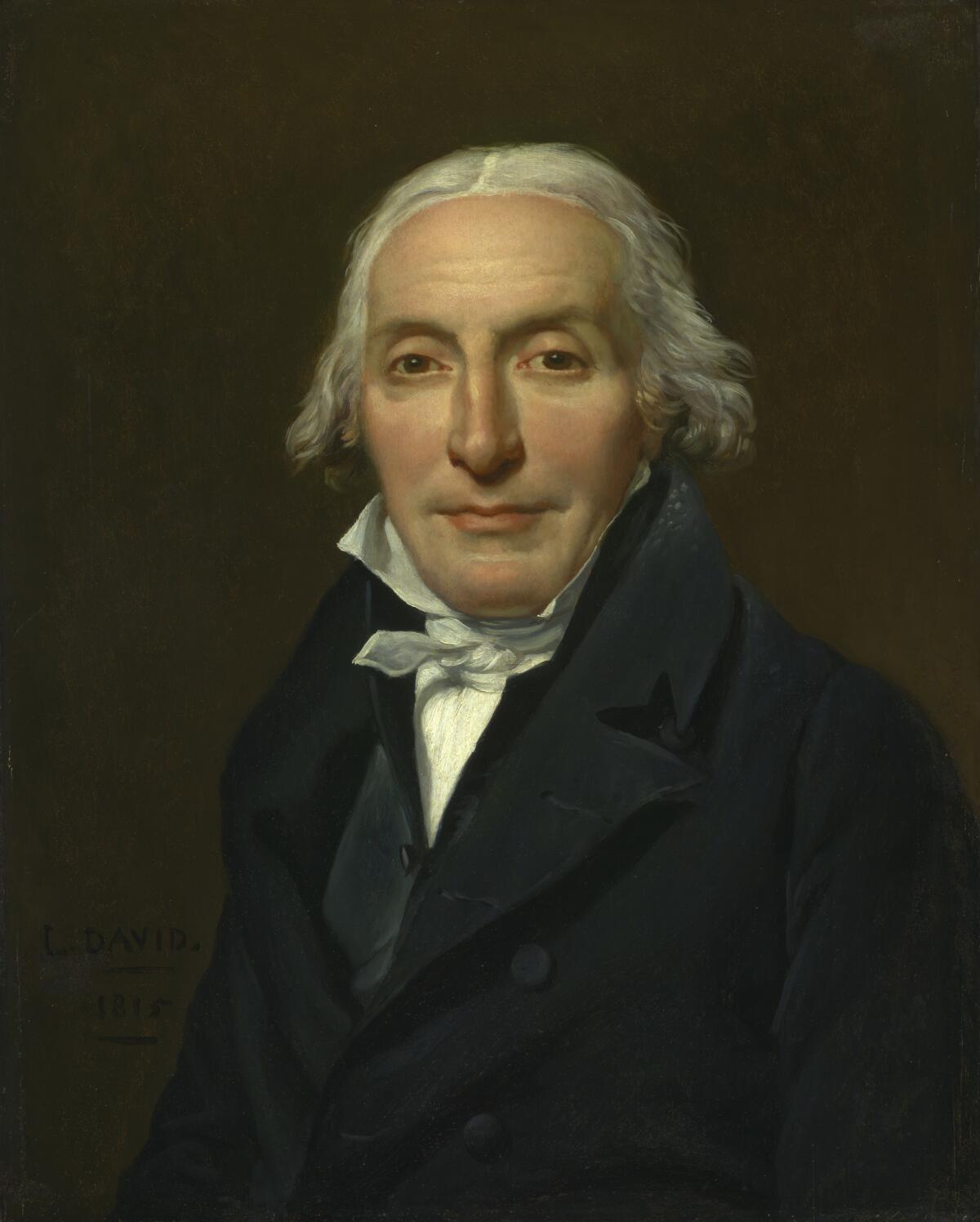

Take “Portrait of Jean-Pierre Delahaye” by Jacques-Louis David, leader of the French Neoclassical movement and Napoleon’s official painter.

“I never thought I would get the painting,” Marandel said of the last work that David completed in Paris, before the defeat of Napoleon forced the artist into exile. “But in 2006, it was put up for auction in Paris. I got it against a dealer who is — or was — a friend of mine.”

The dealer kept “pushing against us” in the bidding, Marandel said, even though the dealer knew that LACMA was in the driver’s seat.

“At the end he said this incredible thing: ‘I could not let you have it for so little money.’ I was very upset. So I said, ‘Well, it’s unfortunate because if you had stopped, I would have bought a painting from you. Now I don’t have any money left.’ It was not quite true, but I let him believe it.”

After Marandel won the $2.7-million competition, LACMA Director Michael Govan called the acquisition “a very big deal for us” (and described Marandel as “a nervous wreck” during the quest to land it). The curator was besieged by French television and a swarm of reporters.

“There was all this publicity and it sort of went to my head,” he said. “So I went to the airport, looked at the planes leaving Paris and flew to Fez, where it was lovely. It was a long way from David to Morocco, but funny things happen when you have to reorient yourself. You cannot just go back to business and have dinner and go to bed.”

“Plague in an Ancient City,” a 17th century painting by Flemish artist Michael Sweerts, purchased for $3.85 million at Sotheby’s New York in 1997, was another coup. But LACMA rarely buys art at auction because the prices are moving targets and securing the resources and approvals is difficult.

Marandel usually worked with a network of trusted dealers, but opportunities could have come from everywhere. Although Old Masters are relatively modestly priced — they haven’t begun to reach the stratospheric prices of Andy Warhol paintings — the curator rejected what he considered to be outrageous offers for a painting of Sleeping Beauty by French artist Marie Antoinette Victoire Petit-Jean and a pair of 6-foot-tall marble sculptures by Italian artist Giovanni Baratta. Marandel snapped them up later only when the price was right.

“Most people don’t realize the skill set involved in connoisseurship and how difficult it is,” Govan said in praising Marandel’s legacy. “Curators can spend millions and make mistakes. It’s a risky business. Patrice has done it with style and aplomb.”

Born and raised in France, Marandel has spent his adult life in the United States, including 13 years as curator of European art at the Detroit Institute of Arts. The LACMA collection he took charge of in 1993 contained “very good things that did not necessarily relate to each other,” he said. “I wanted to build bridges between these things and add to them, and redesign the galleries completely, to give some kind of order to it.”

The challenge was made more enticing by the Ahmanson Foundation, which provides funds for the museum to buy European Old Master works.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

“I can boast that I have a 100% success rate with them,” Marandel said. “I’ve always been a bit envious of museums that have larger acquisition funds, but it is easier to deal with a small group of interested people than with a board that’s always looking at other things. It’s a more personal relationship that has worked well for me.”

Apparently the feeling is mutual.

“Patrice has a knack for finding works of value that are consistent with the collection and appealing to the public, as well as academics,” said William H. Ahmanson, president of the foundation. “We look forward to what he finds every year, with eager anticipation.”

Marandel’s first Ahmanson purchase, in 1994, was “Sir Wyndham Knatchbull-Wyndham,” a portrait by Italian artist Pompeo Batoni that had been in the family of the elegantly attired Englishman since 1759, when it was painted.

“Usually you don’t meet the people who own the paintings,” Marandel said. “You meet the dealers who have the paintings on consignment.” He was surprised by an invitation to meet the Batoni seller and — after traveling to England — completely unprepared to learn that she was Countess Mountbatten, great-great-granddaughter of Queen Victoria.

“Suddenly I was thrown into this world of an aristocratic English family, something I knew nothing about,” he said. “I didn’t even know how to address these people.”

Now a veteran of such adventures, Marandel got high marks from colleagues such as Keith Christiansen, chairman of European paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

“Patrice is an extraordinary curator whose broad interests and keen sense of quality have informed his many acquisitions,” Christiansen wrote in an email. By rehanging the European galleries at LACMA, Marandel “laid out a narrative of wonderful richness that made a visit to the museum very special. Wonderful juxtapositions, great works by well-known masters alongside others by lesser known or unfamiliar artists, but with individual voices. Is this not what we look for in a major institution?”

Marandel has a two-year contract to serve the museum as a consultant, and his stories will be preserved in a book, “Abecedario: Collecting and Recollecting,” to be published this spring by Art Catalogues/LACMA. His successor has yet to be named, Govan said. In the interim, curator Leah Lehmbeck will oversee the department.

“There is a bit of sadness,” Marandel said of his departure. “I hope it’s not pretentious to say that LACMA is a little bit my museum. But it should move on and be reappraised by someone else and enjoyed differently.”

Follow The Times’ arts team @culturemonster.

ALSO

Times art critic Christopher Knight’s latest reviews

Times theater critic Charles McNulty’s latest reviews

Times architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne’s latest columns

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.