Review: Why Andriessen’s daring and difficult ‘Theatre of the World’ will stand the test of time

Louis Andriessen is the great argumentative opera composer of our day. He argues with every convention of the lyric stage. He is, moreover, a master of operatic argument, which is the traditional term for plot in not just its narrative sense but also its moral, spiritual, political and temporal implications. He is a clear-eyed Dutch skeptic and humanist who surfs the alarmingly narrow arteries that separate life from death, wisdom from belief, the known from the unknown. He has cannily called himself a friendly guy who doesn’t always write friendly music.

We now have “Theatre of the World,” the fifth and most querulous opera from a guy whose work is not always friendly but is always extraordinary. In a remarkable gesture for even the progressive Los Angeles Philharmonic, the orchestra commissioned the opera and gave its world premiere in a fully staged and fully contentious production in Walt Disney Concert Hall on Friday night and Sunday afternoon. Made into a nightmare theater of a fraught and sinister world by director Pierre Audi, this co-production with Dutch National Opera will be a centerpiece this June of the Holland Festival in Amsterdam.

The two performances were enough for this longtime Andriessen advocate to begin to fathom a dizzying work that’s vast in its scope yet unnervingly claustrophobic. Musically, it is brilliant and deep. Operatically, well, there is a lot to take in.

The subject matter is Athanasius Kircher. The Museum of Jurassic Technology in Los Angeles has a room devoted to this peculiar and very real 17th century polymath’s curiosities. His investigations included, but were hardly limited to, Egyptian hieroglyphics, the civilizations of ancient China and Babylon, the natural elements, music, mathematics and optics. During his life, he was the world’s most sought-after scientist and inventor while being a Catholic spiritualist with a fancy for the ultra-exotic and cockamamie.

It could be said that Kircher had more use for essence than truth, and that might also be said about the novels that mix fact with fiction of the German writer Helmut Krausser, who wrote the problematic Faustian libretto for “Theatre of the World.” Krausser’s Kircher is at the end of his life and the end of his rope. His Herculean attempts to find a unified theory of all natural and unnatural phenomena based on magnetism has given him a kind of psychic mercury poisoning.

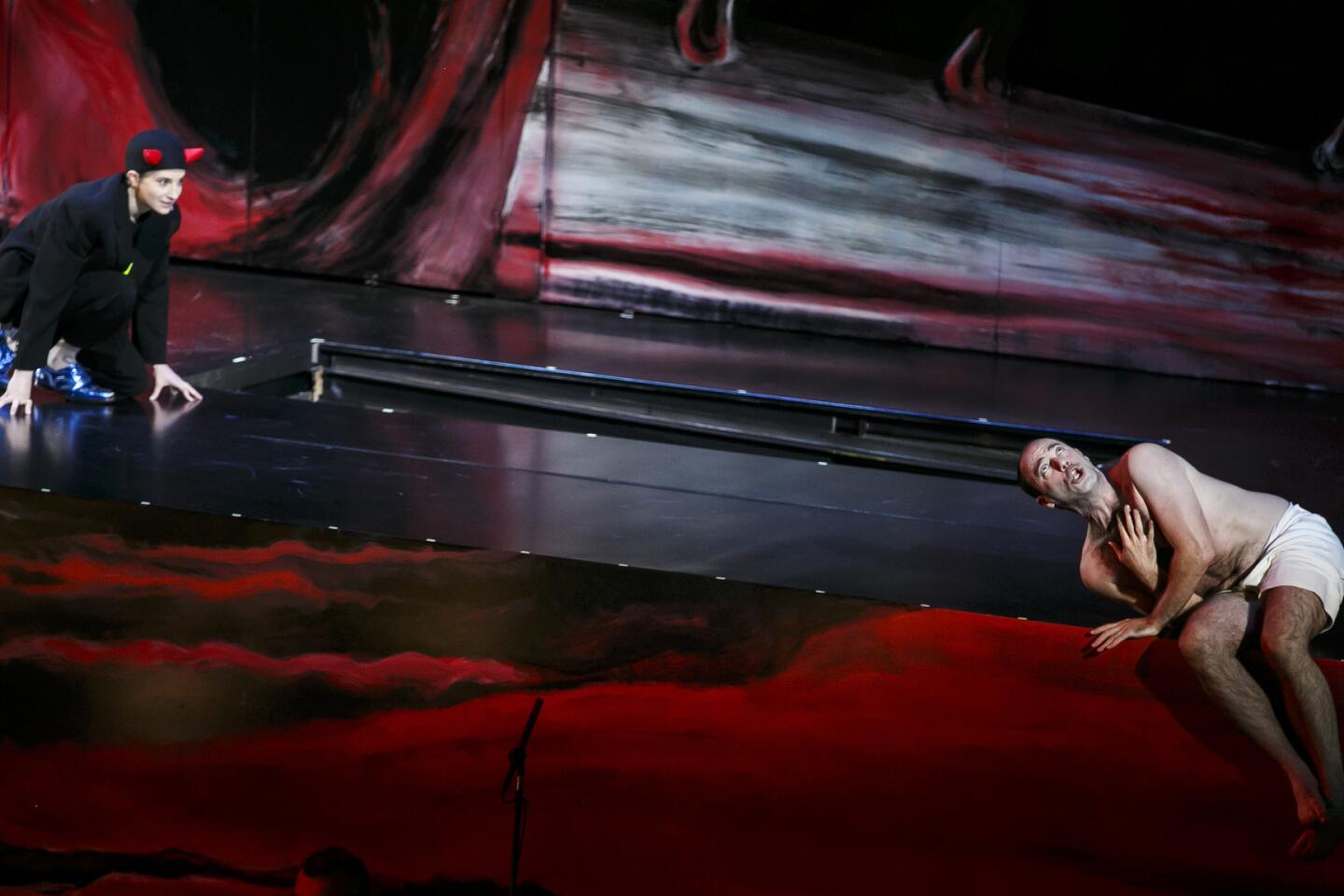

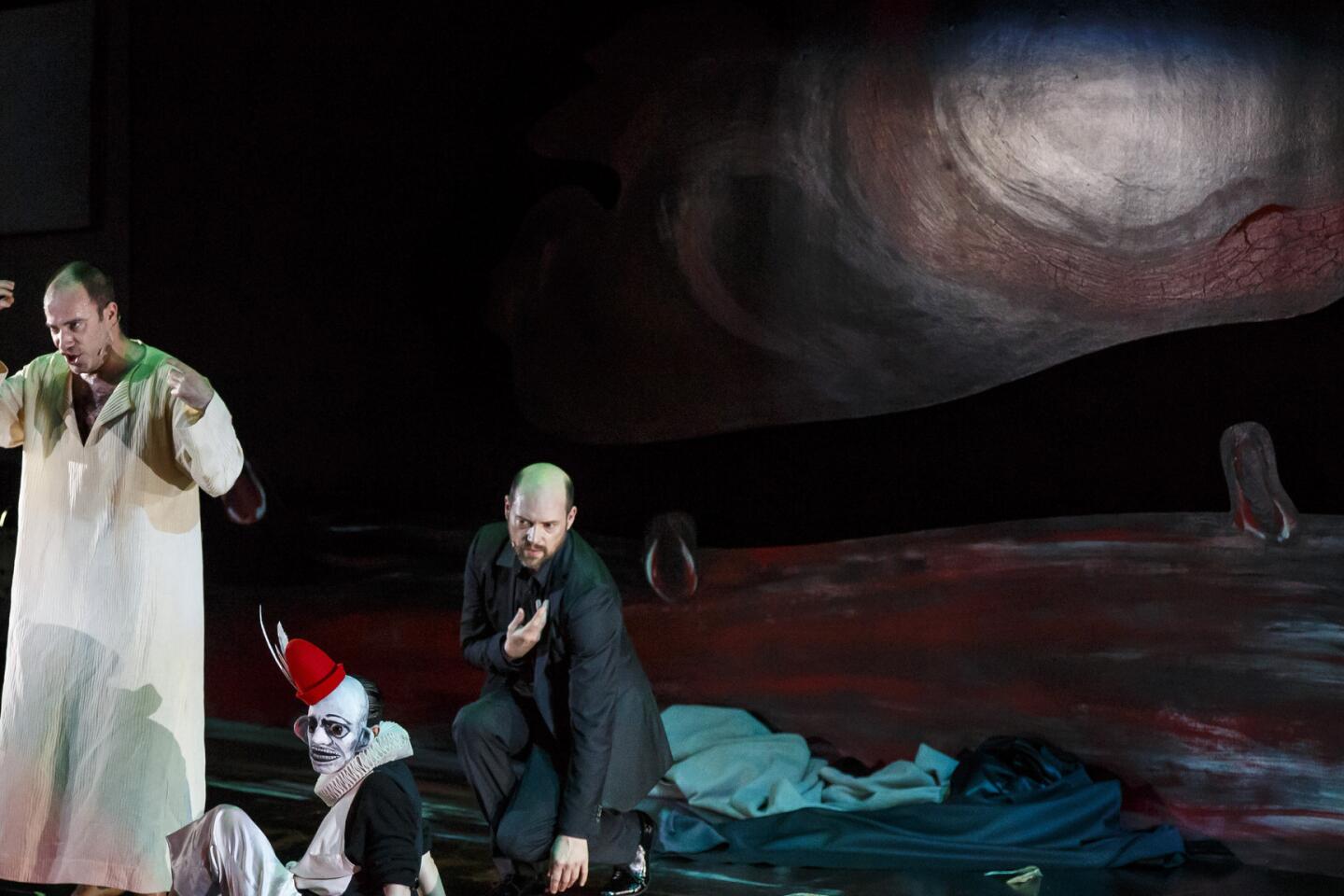

He is overwhelmed by it all, and it is not very long before we will be as well. The subtitle of the opera is “A Grotesque Stagework in 9 Scenes.” Kircher is confronted by a boy who turns out to be the devil in disguise, and off they go, accompanied by Pope Innocenzo XI and Kircher’s Amsterdam publisher, transported to ancient Egypt, China and the Tower of Babel. A trio of murderous witches keeps popping up as does an executioner. At one point a pair of young lovers appears out of nowhere, singing a disarmingly lovely duet.

More important, Sor Juana Inès de la Cruz, the Mexican nun and poet, becomes Kircher’s real spiritual guide and conscience. She and Kircher corresponded, and several scenes end no longer as grotesqueries but in the thrall of Andriessen’s unearthly settings of her ethereal lyrics. In an epilogue, Voltaire, Descartes, Goethe and Leibnitz give Kircher a break for flying on the wings of imagination.

All of this is just the beginning of a confusing production, a musically rich score and a sensational performance. But the production by Audi treats all this as a weirdly oppressive nightmare. Décor and video by the Quay Brothers add further grotesqueries, the avant-garde American animators framing video of inconsequential monochrome stop-motion animatronics with gigantic red brushstrokes. The eye flies from this to the stage action to the projections of a complicated, text-thick libretto in German, Dutch, English, Italian and Spanish and Latin. Florence von Gerkan’s costumes make everyone unsympathetic.

Andriessen’s music, however, compels from start to finish. The first among Andriessen’s musical arguments are with the orchestra. The L.A. Phil is the rare ensemble he has been willing to enter into a long-term relationship with. The band here is chamber-sized, heavily balanced toward winds, brass and percussion, and it includes electric guitars and synthesizer to make sure his trademark “bang bang” business gets a full workout.

Those first notes are trombone playing a haunting motive that has the aspect of Renaissance brass music and a Minimalist fragment and that can grow later on in the opera into a something almost cosmic. The music changes almost constantly. The lovers might be straight out of sensual 18th century opera. The witches get a big-band jazz treatment. Musical angst galore comes Kircher’s way. The boy is a Stravinskian-style devil. The pope is a hysteric tenor.

Reinbert de Leeuw, who has conducted the premieres of all of Andriessen’s operas, captures the score’s ever-changing everything. There are quick successions of six or seven different genres (and three or four centuries’ worth) of dance music, updated Renaissance era counterpoint, 20th and 21st century Minimalism, hard-hitting clusters of dissonance and ice-cream sweet scopes of consonance. De Leeuw also managed with precise skill the difficult balances between unamplified orchestra and the punchy amplified voices that Andriessen adores.

Leigh Melrose (Kircher), Lindsay Kesselman (the boy/devil), Marcel Beekman (Innocenzo XI), Steven van Watermeulen (Janssonius, Kircher’s Amsterdam publisher), Mattijs van de Woerd (Carnifex, the hangman) all seemed possessed of the opera and Andriessen’s vocal writing, as did the witches and philosophers and lovers.

Still, it was Cristina Zavalloni’s ravenously ecstatic Sor Juana who is the real vocal soul of the opera as she is of Kircher.

An opera like this is not easy on symphony audiences who aren’t likely to come early enough to prepare and come early enough to read the program notes, without which they are lost. The opera (110 minutes Friday, a quicker-played and more exciting 105 minutes on Sunday) was performed straight through. An intermission would have allowed audiences to get their balance and made it easier for those who didn’t want the balance to leave.

But while patrons may give the orchestra a hard time over this one, history may not. And there will be evidence. The performances were recorded for eventual commercial release.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.