Critic’s Notebook: Mural uproar teaches LAUSD a lesson: Artists have a moral right against censorship

The Los Angeles Unified School District is belatedly learning an important lesson. Artists have moral rights that protect their work.

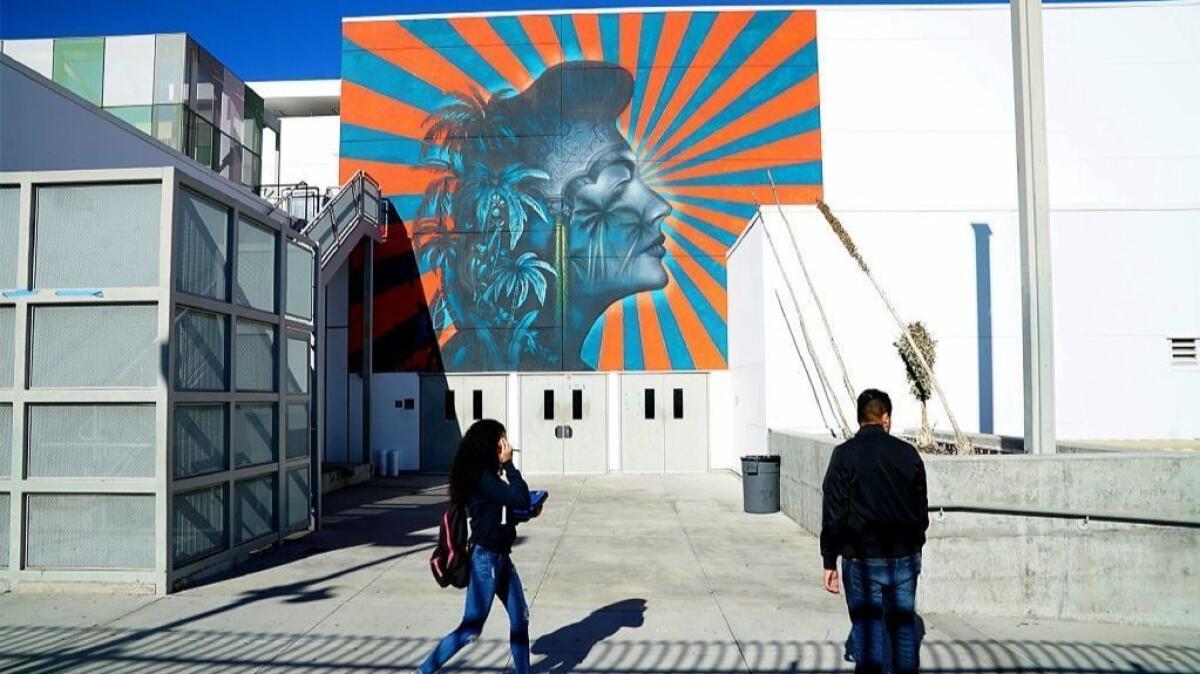

LAUSD stepped back on Monday from its plan to censor a mural at the Robert F. Kennedy Community Schools on the Koreatown site of the old Ambassador Hotel. The district stated no specific cause for the reversal, but it took a small step in the right direction.

The raging censorship controversy around the painting could not help but bring to mind the federal Visual Artists Rights Act, enacted by Congress in 1990. That law responds to the defacement, mutilation or destruction of works of art. For the first time in U.S. history, federal law recognized an artist’s moral rights.

In a stunning irony, Sen. Edward M. Kennedy, brother of the slain presidential candidate for whom the Koreatown school is named, introduced the law to Congress.

The imperiled mural, painted without incident more than two years ago, depicts actress Ava Gardner with symbols of the Cocoanut Grove, a nightclub once the epicenter of the Ambassador complex. Protesters mischaracterized the 44 blue and red rays in the portrait’s background as the Japanese imperial battle flag — a banner that actually features a red disk with 16 crimson rays against a white ground.

A small but voluble Korean American neighborhood group pressured school officials to remove the mural anyhow. LAUSD announced the painting would be whitewashed during the holiday break. Now, faced with rising public criticism of the imminent censorship plan, a final verdict has been postponed until an unspecified future date.

Monday’s 180-degree about-face was as abrupt as the original judgment to censor the mural. No doubt it was pushed along by two sharp rebukes.

The first came from Robert F. Kennedy Jr., following the lead of a complaint offered by his younger brother Max. Kennedy wrote to school board chair Monica Garcia and district administrator Roberto Martinez that “citizens who love democracy will flock to the barricade to shield artists from government censors (including LAUSD!).”

The second scolding came from Paul Schrade, the other person shot in the head on the awful night of Robert Kennedy’s 1968 assassination at the Ambassador Hotel. (The school’s library is named for Schrade.) Now 94, he lamented that the district’s actions “violate the legacy of freedom and justice” embodied by the RFK schools’ namesake.

If whitewashing the mural does proceed, however, don’t expect it before March. Those pesky moral rights stand in the way of precipitous action.

The 1979 California Art Preservation Act erected steep obstacles to any mutilation or destruction of a work of fine art. The federal law goes even further — including a provision that could have made the rash decision to obliterate the mural during winter break a very expensive proposition for LAUSD.

The Visual Artists Rights Act stipulates a minimum waiting period of 90 days after an artist has been formally notified of, never mind given consent to, the destruction of his work. The most recent whitewashing case to run afoul of both those state and federal laws — Kent Twitchell’s obliterated six-story portrait of Edward Ruscha on the side of downtown L.A. building — cost the offending party almost $1.1 million in settlement payments.

The school district had estimated the cost of painting out the Ava Gardner mural at $20,000. That might cover the cost of scaffolding and labor, but I suspect it would barely put a dent in an inevitable lawsuit.

Legal wrangling is of course a messy business. (Beau Stanton, the mural’s artist, has reportedly retained a lawyer.) Art that is made for hire, as commissions often are, can be exempt from VARA protections, but trampling on a 1st Amendment guarantee of free speech is a bad look for a school.

A 90-day waiting period is designed to prevent a heckler’s veto. It means to defuse exactly the kind of rush to judgment that LAUSD made when faced by noisy opposition. The hope is that cooler, more thoughtful voices will emerge.

In recent days those voices have been coming to the foreground.

Street artist Shepard Fairey announced that he would seek to remove his own mural — a portrait of Robert F. Kennedy that is the school’s signature image — if Stanton’s was destroyed. Four other muralists with works at the site — Berlin-based American artist James Bullough; Bay Area-based Allison Torneros, known as Hueman; and Cyrcle, the Los Angeles based artist-duo David Leavitt and David Torres — told The Times they would do the same.

On Monday, a podcast produced by the website Korean American Heritage condemned the censorship in no uncertain terms. Interview guest Dave Young Kim, an Oakland-based Korean American artist familiar with Stanton’s mural, expressed profound skepticism over the complaint’s legitimacy.

Podcast co-host Philip Ahn Cuddy dismissed the protesters’ complaint outright, calling it “petty baloney.” Cuddy’s maternal grandfather, Dosan Ahn Chang Ho, was a renowned Korean independence activist imprisoned by the Japanese imperial government, while his American-born uncle, character actor Philip Ahn, appeared with Ava Gardner in the 1947 movie “Singapore.” Cuddy challenged the protesters’ claims to speak for the larger Korean American community.

The dispute is not, as the pious protesters claim, over ignoring atrocities committed by the long-defunct Empire of Japan.

On Dec. 8, 1941, the day after Pearl Harbor, my husband’s family in the Philippines lost almost everything — their home, their business — when the empire attacked Manila. They fled the city on foot, carrying what they could more than 150 miles into the mountains, seeking shelter and living for the next several years in the side chapel of a church. His uncle, surreptitiously working as a courier for the U.S. Army, was captured and imprisoned by the Imperial Japanese Army, barely surviving the notorious Bataan Death March, among the cruelest war crimes of a century that was no stranger to them.

The story is awful but not unique. Thousands of families have them. The dispute in Koreatown is over bowing to an intolerable demand for censorship, a moral offense that cheapens the punishing struggle countless people have endured. LAUSD should not be an instrument for that.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.