Review: Henry Taylor at Blum & Poe Gallery

The people in paintings by Henry Taylor tend to loom. Not in a grandiose or threatening way, but in a portentous one. These people matter.

Eleven large paintings are included in an ambitious exhibition at Blum & Poe gallery. The figures are ordinary folks doing ordinary things — getting their hair done, floating in a swimming pool, even just sitting for a portrait to be painted. Yet they feel momentous, vital — which seems to be the point.

Taylor paints in a drawing style, wielding a loaded monochrome brush in firm strokes. Figures typically dominate the frame. He color-blocks a hand, the slats of a folding chair, a baseball cap and other elements, including the negative space surrounding them. Color is mostly high-contrast. The brushwork overflows with deliberateness.

Taylor has dispersed the paintings in three rooms, each set up like a theatrical stage-set.

The first mise-en-scène is a dry and dusty urban field of dirt sporting a dead tree, graffiti on the walls, an old water pump and a homeless encampment tucked behind a tumbled-down wall. The second is a backyard swimming pool surrounded by a grassy lawn.

Finally comes an artist’s studio, complete with work table, a wall full of small portrait studies, a bin of miscellaneous stuff and some chairs. Arriving at the cozily cluttered studio after earlier scenes of alienation and recreation is poetically evocative. Tribute is paid to art as a social mechanism.

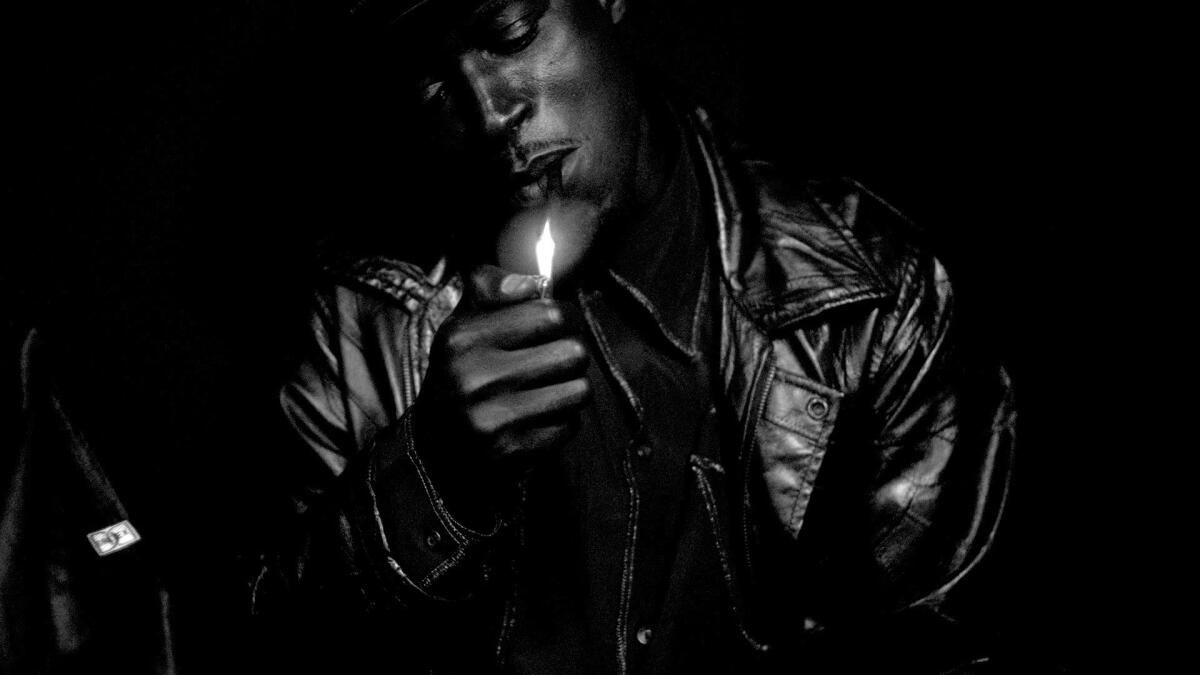

Into this mix the artist has invited a memorable, like-minded contribution from filmmaker Kahlil Joseph, a friend and colleague. Joseph has fashioned a fourth stage-set: a dimly lighted room painted black and ringed with folding chairs. Ashtrays, a bottle opener and a few stray roaches litter a card table beneath a shrouded fluorescent light.

With a celestial musical soundtrack, projected images from a two-channel video of a black-and-white film float in and out of view. The movie title, “Wizard of the Upper Amazon,” refers to legendary Brazilian herbalist Manuel Córdova-Rios.

Like a dreamy memory, it shows the interior of the same room a viewer is sitting in, but now the seats are populated mostly with black men smoking joints. The friendly Rastafarian social ritual of sharing ganja is purported to open a connection with the divine.

The film and stage-set loosely recall an encounter Taylor had with Jamaican reggae singer Bob Marley more than 30 years ago, backstage at a Santa Barbara County Bowl concert. (“SBCB” is stenciled on the chairs.) But this deft exhibition isn’t merely a celebrity reminiscence. Politically, it could not be timelier.

In April, Harper’s magazine reported confirmation from a top adviser to former President Nixon of a long-held suspicion: In wake of civil rights movement successes, draconian new drug laws were partly envisioned as a way to harass and imprison African Americans.

“We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news,” John Ehrlichman reportedly said before he died. “Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course, we did.”

Plainly, Taylor and Joseph know too. They’ve fashioned a seductive and affecting rejoinder to the news.

Blum & Poe, 2727 S. La Cienega Blvd., Culver City. Through Nov. 5. , (310) 836-2062, www.blumandpoe.com

Twitter: @KnightLAT

ALSO

Abraham Cruzvillegas' deft view of L.A. car culture at Regen Projects

Tacita Dean's remarkable hand-drawn cloud prints at Gemini G.E.L.

MOCA's Gaetano Pesce exhibition stumbles across a bright ethical line

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.