L.A. helps Havana’s vintage neon signs glow again: ‘It marks a new era, a return of the light, of hope’

Reporting from Havana — As the sun sinks over Old Havana, a row of ramshackle apartment buildings fades from sherbet bright to creamy hues of pale pink, yellow and green. Storm clouds hover above the twisty streets bustling with bike taxis, grocery-carting pedestrians and classic cars. Couples linger at outdoor cafés, stray dogs crisscross the cracked, uneven sidewalks.

Then the lights come on.

First, it’s the golden neon sign atop the 1950s-era Payret Theater by Central Park. Then, in the shadow of the National Capitol Building, the ice-blue marquee fronting the now-dormant Cine El Mégano comes alive.

“¡Es magia!,” squeals a little boy, grasping his mother’s hand.

It’s been decades since Havana’s neon signs have infused the city with so much light. But with the public art and urban restoration project Havana Light, neon is glowing again in Cuba.

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour >>

The initiative is the brainchild of Cuban contemporary artist Kadir López Nieves and Cuban-born Angeleno Adolfo Nodal, who was general manager of Los Angeles’ Department of Cultural Affairs for 12 years, starting in the late 1980s. Nodal now lives half the year in Havana. During his tenure at the L.A. agency, he had more than 150 vintage neon signs restored in Hollywood, downtown and along the Wilshire corridor, including the Bendix and Knickerbocker hotel signs.

Inspired by that project, Nodal and López Nieves, who met in Cuba’s art scene a decade ago, are now immersed in a self-funded effort to illuminate Havana, one sign at a time.

The neon logos topping hotels, theaters and restaurants — both artfully repaired vintage signs and new commercial ones — are part of the historic preservation of Old Havana during a moment of profound change. They are emblematic of, and meant to inspire, the budding entrepreneurship taking place in Cuba now that citizens may open small businesses and the thawing of U.S.-Cuba relations makes travel to the island easier.

“It marks a new era, a return of the light, of hope,” Nodal says on a walking tour of the signs in Havana.

In the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s, Nodal says, thousands of commercial neon signs, then thought of as a symbol of modernism and prosperity, crowded Havana’s streets. The city boasted as much neon as Paris and New York. The blur of candy-colored lights lent a moody, noir chic to the island’s vibrant jazz scene, sparking the nickname “the Paris of Latin America.”

Havana was dead ... And now Havana is living again, with the new lights.

— Osmany Fernandez, Havana Light project electrician

But after the rise of Fidel Castro’s socialist government in the 1960s, the signs were seen as grossly commercial. They were also expensive to maintain due to decay from humidity and harsh sunlight. Slowly, they were taken down or turned off. After the fall of communism in the Soviet Union in 1991, Cuba faced a so-called special period of dire economic conditions and daily power shortages; nearly all the remaining neon signs went dark. Many were used as scrap metal.

“We want to spark an interest in neon, a resurgence, so that new businesses coming in will opt for it,” Nodal says. “They serve the city in such a beautiful way — they’re public sculptures.”

The signs at the Payret and Mégano theaters were the first two Nodal and López Nieves restored, working with one of Cuba’s only neon glassblowers, Guido Hernandez, and his proteges. The signs debuted atop their original locations along with eight others around the city as part of López Nieves’ art installation “Alumbrando el Barrio” (Lighting Up the Neighborhood) in conjunction with the May 2015 Havana Biennial.

Polito Ibanez rocks out at Havana Light backyard fundraiser.

With a third partner, L.A. businessman William Merriken, they have completed 42 signs so far, mostly concentrated along Paseo del Prado in Old Havana, the Malecón waterfront and 23rd street — “the route of the light,” as they call it. Some signs are attached to still-operating establishments, such as the Hotel Inglaterra and the Hotel; others, like the Mégano sign, sit atop abandoned businesses.

The goal, says Nodal, is to light 150 signs in the next two years. The two eventually hope to eventually reach 500 signs and are also exploring the possibility of solar-powered neon.

“It’s been a long season of darkness,” López Nieves says. “But Cuba is finally open socially, open to the world. And the world is just opening to Cuba. Whenever we display one sign, there’s an immediate impact. People start looking at their environment in a different way.”

To restore the signs, neon benders re-shape the glass by hand, spiff up the rusty metal frames, add electrodes and fill the signs tubing with gas, in the same manner they were created in the 1930s. López Nieves sources old photos and newsreel footage for clues as to what the signs looked like in their heyday; he then sketches blueprints for the craftsmen. “I have to guess what color they were and what will work best,” López Nieves says, since he’s working mostly off black-and-white images.

Despite decades of urban decay and a lack of infrastructure development in Havana, Nodal says restoring that city’s signs has been easier than in L.A., where it took more than a decade to accomplish, due to what he calls “regular bureaucracy.” With Cubans now allowed to own property, a legislation change as of 2011, building ownership in the country is slowly shifting from state to private hands. In this murky, transitional landscape, the unlit unlighted signs, he Nodal says, are considered in the public realm.

He and López Nieves simply obtain permission from a building manager, if there is one, and neighbors. When the neon lights go on for the first time, Nodal says, residents typically cheer. “The government doesn’t really have a role; it’s happening on the neighborhood level. People are so eager for progress, there are very few naysayers.”

Funding is the primary challenge: restoration costs roughly $700 to $3,000 per sign, each of which takes one to three weeks of labor, López Nieves says. Where L.A.’s neon project was city-funded, Nodal and López Nieves are paying for Havana Light through online crowd funding, fundraising parties, their own money and paid tours of the signs around Havana. They’re in the process of building an income-generating museum for neon signs and classic cars — “the old bones of Havana,” Nodal says. When it debuts in 2017, it will be one of Cuba’s only nongovernment, artist-run spaces. It will also include a garage workshop where the project’s restoration work can be done and new commercial neon signs can be made for Havana businesses willing to pay for the service. The glassblowers and electricians get paid for their work, so the project is creating jobs, as well; but Nodal says he and López Nieves don’t take any money.

“One hundred percent of the profits go back into restoring the signs,” Nodal says. “It’s a labor of love.”

On a recent May evening, dozens of Dallas tourists visited López Nieves’ home in the Kohly area of Havana for a tour of his gallery works, followed by a backyard pig roast and live concert by local indie pop artist Polito Ibáñez. Vintage signs dotted the yard, bathing the party in green, red and yellow neon. The raucous Dallas collectors, some in cowboy hats and faded jeans, mingled beneath leafy palms and mango trees as Ibáñez’s band rocked out on a small stage by the pool.

The evening was productive: López Nieves sold two large pieces, and in all, the event generated about $10,000 for the project.

“Havana was dead,” an electrician employed by the project, Osmany Fernandez, said over corn tamales and red wine. “And now Havana is living again, with the new lights.”

It marks a new era, a return of the light, of hope.

— Adolfo Nodal, Havana Light

From a purely practical standpoint, Nodal says, the signs illuminate previously dark and dangerous nooks of the city.

“Guns aren’t easily accessible in Cuba, so you don’t see many murders, robberies,” Nodal says. “But there’s petty crime, there’s prostitution. Whenever you have light, that stuff goes away.”

Nodal makes his living as co-founder of Cuba Tours and Travel. “I’ve learned how tourism can fuel culture,” he says.

He and López Nieves bought a house earlier this year for their neon museum conveniently located across the street from the Hemingway House, in San Francisco de Paula, just outside Havana. The boneyard for neon signs and classic cars will be located in the backyard “to tell the story of Havana neon, the history of Havana,” Nodal says. When it debuts in 2017, it will be one of Cuba’s only non-government, artist-run spaces, along with relatively new ventures such as Fabrica de Arte.

“We wanted to be where those big buses, that take all the tourists around, go by,” Nodal says.

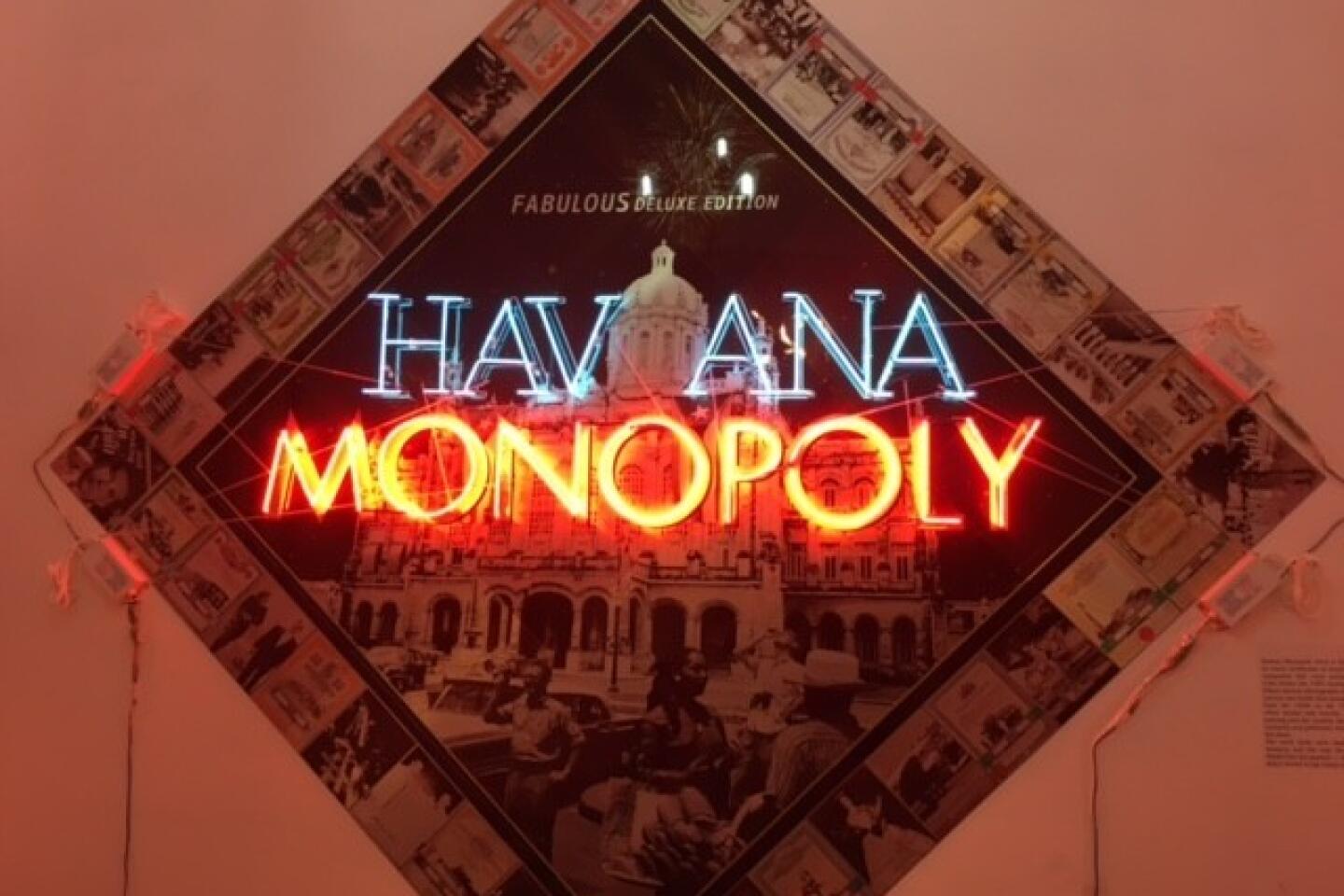

López Nieves earns a living by selling his smaller gallery works internationally. In 2014, he exhibited, painted and photo-collaged non-neon metal signs that he’d found around Havana — the focus of his art practice over the last decade — at Santa Monica’s William Turner Gallery. He’ll exhibit new work at L.A.’s Gallery 825 in August, as well as a neon installation, “Havana Noir,” at the Palos Verdes Art Center this fall.

“My work is based in memory and how layers of memory affect the future,” López Nieves says. “The whole spirit of Cuba today has a lot to do with that.”

Soon, they the two will restore Havana’s 1940s-era movie theater, the sign on the Los Angeles, a vintage movie theater where Hollywood films premiered in Cuba in the ’40s and ’50s. The sign restoration is being funded by L.A.’s Project Restore; an L.A. delegation will fly to Havana next in March to light the sign. “It’s the neon equivalent of planting a tree,” Nodal jokes. “It represents peace, a relationship.”

“The project, it’s breaking ground, it’s opening doors,” says Project Restore President Ed Avila. “And for us, it’s the beginning of a friendship.”

“It’s been a long season of darkness,” López Nieves says. “But Cuba is finally open socially, open to the world. And the world is just opening to Cuba. Whenever we display one sign, there’s an immediate impact. People start looking at their environment in a different way.”

“It gives people an idea of what they lost,” Nodal adds, “and what the possibilities could be.”

Follow me on Twitter: @debvankin

ALSO:

In Havana, following a USC museum director in search of great Cuban art

Cindy Sherman reveals her latest body of work — and it’s personal

At Hammer Museum’s ‘Made in L.A.’ biennial, Martine Syms makes her moment

The late Cuban artist Belkis Ayón’s mysterious world unfurls at the Fowler Museum

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.