King Tut gets a remodel: How conservators are trying to protect the tomb from tourists

With a new King Tut exhibition packing in the crowds in Los Angeles, the Getty Conservation Institute announced Tuesday that it has nearly finished a multiyear project focused on conserving the tomb of Tutankhamun and protecting it from the tourist hordes in Egypt.

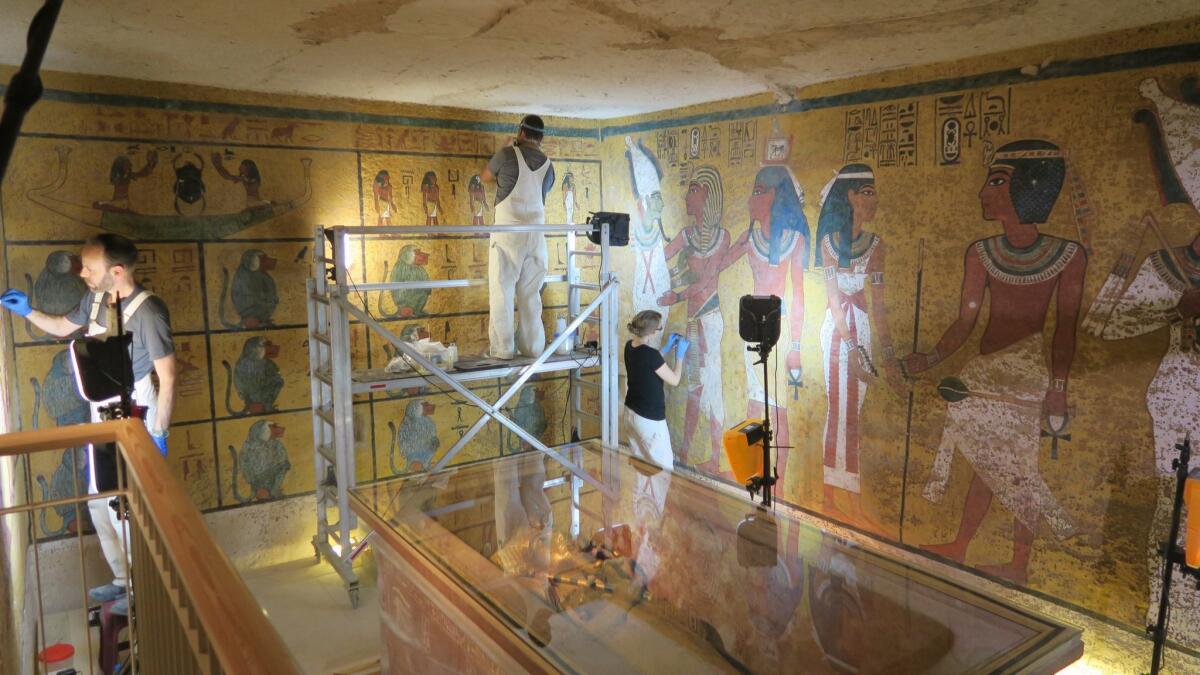

The Getty Conservation Institute carried out the work in collaboration with Egypt’s Ministry of Antiquities. It included the conservation of wall paintings, improvements to the tomb’s infrastructure and environmental systems, and the training of stewards for the site.

Researchers conducted an intensive study to understand the tomb’s condition, assess the causes of deterioration and decide how best to address them, said Neville Agnew, the GCI senior principal project specialist who oversaw the project.

“It’s the preparation work that is so meticulous,” he said. “It’s diagnostic, medical — you have to diagnose before you can treat.”

There’s no more exciting or interesting area of endeavor than preservation.

— Neville Agnew, leader of the King Tut tumb conservation project

The Egyptian government has long worried about the potential effects of visitors, whose presence can change the air quality and humidity inside the tomb, threatening the artwork.

GCI began work in 2009 but lost about four years because of tumultuous political events including the 2010 Arab Spring and the 2013 coup that removed President Mohamed Morsi from power.

Despite all the tumult, Agnew said, to his knowledge the tomb has never closed to the public.

“Our conservation work was conducted with many onlookers from the viewing ramp,” he said.

The tomb’s contents have toured the world for years; “King Tut: Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh,” on view now at the California Science Center in L.A.’s Exposition Park, contains more than 150 objects. But many items do remain in Egypt, including the mummy of the 19-year-old ruler, the quartzite sarcophagus with granite lid, the gilded wooden outer coffin and a series of wall paintings.

Protecting those wall paintings from the accidental scratches of a visiting public was a top priority for GCI. A new barrier has been erected to keep people a safe distance from the art. Other additions include walkways, a viewing platform and an air filtration and ventilation system to control humidity and carbon dioxide levels.

In the past, dust brought in by tourists dimmed the paint and required cleaning that posed the threat of paint loss. The Getty team removed the dust and reduced coatings from previous treatments. Protocols were put in place to monitor on future deterioration.

Signage, originally only in English, is now in Arabic as well. New lighting is slated for the fall. A January symposium will feature Egyptologists discussing the particulars of the conservation effort. A project monograph and a book for the general public are planned.

“One learns a great deal about other cultures, and dealing with other cultures, and one learns history too,” Agnew said of preservation work. “There’s economics, science, meteorology, analysis, cultural sensitivity, chemical analysis, engineering. All these things are required.”

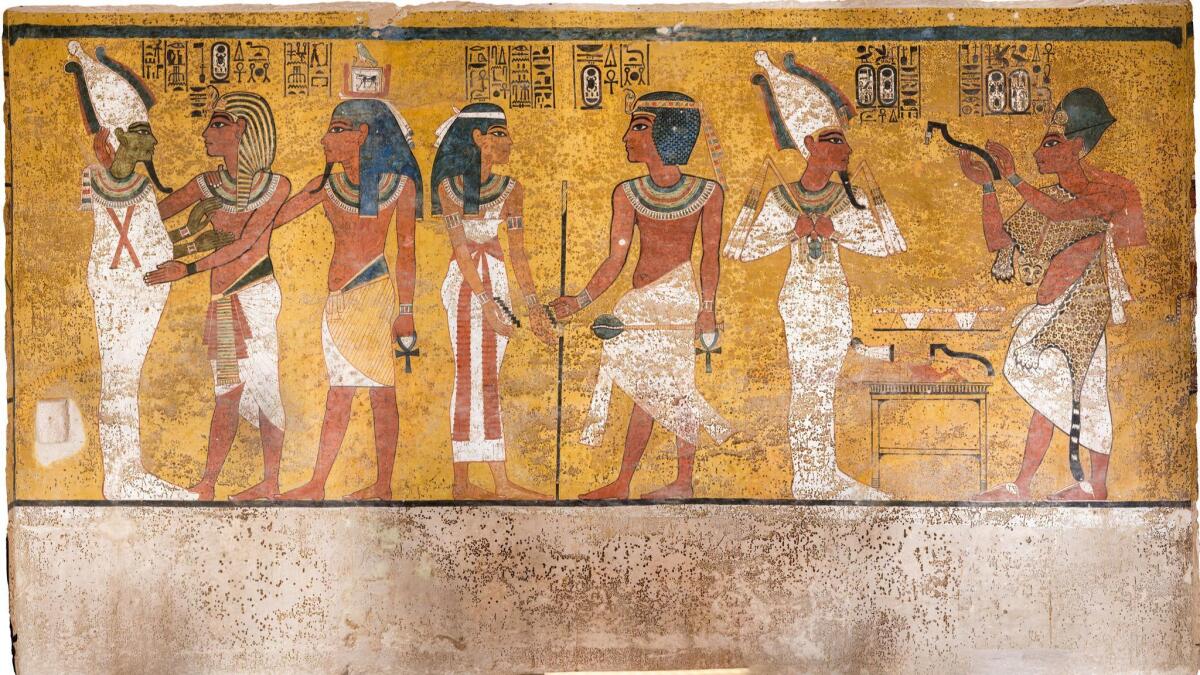

One of the most intriguing aspects of the Tut project, Agnew said, was the evaluation of mysterious brown spots that marred the wall paintings. The spots were already present in 1922, when Howard Carter made his discovery in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings, after the tomb had evaded plunder for more than 3,000 years thanks to a flood that buried the entrance with debris.

Egyptian authorities wondered if new visitors were causing those brown spots to grow. DNA and chemical analysis confirmed that the spots were created by microbiological organisms that were dead and therefore not capable of spreading. The spots were left alone because they are embedded in the paint and because they reflect the history of the site.

“It tells us something archaeologically about the tomb,” Agnew said. “It tells us that the tomb was certainly sealed when it was wet. Tutankhamun was 19 when he died. He wasn’t expected to die. They hastily overhauled a smaller tomb, hastily entombed him, and sealed it up. Not only was there wet plaster in the walls, there was lots of organic material — wood and flower offerings, all of which contain moisture and promote microbiological growth.”

ALSO:

Large gift of Southern art for California African American Museum

Lucas Museum of Narrative Art: New renderings

MOCA still mum about curator’s firing

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.