An L.A. art star turns 50: Gemini G.E.L. celebrates with a LACMA exhibition

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art will present a survey exhibition of Gemini G.E.L. works from 1966 to 2014.

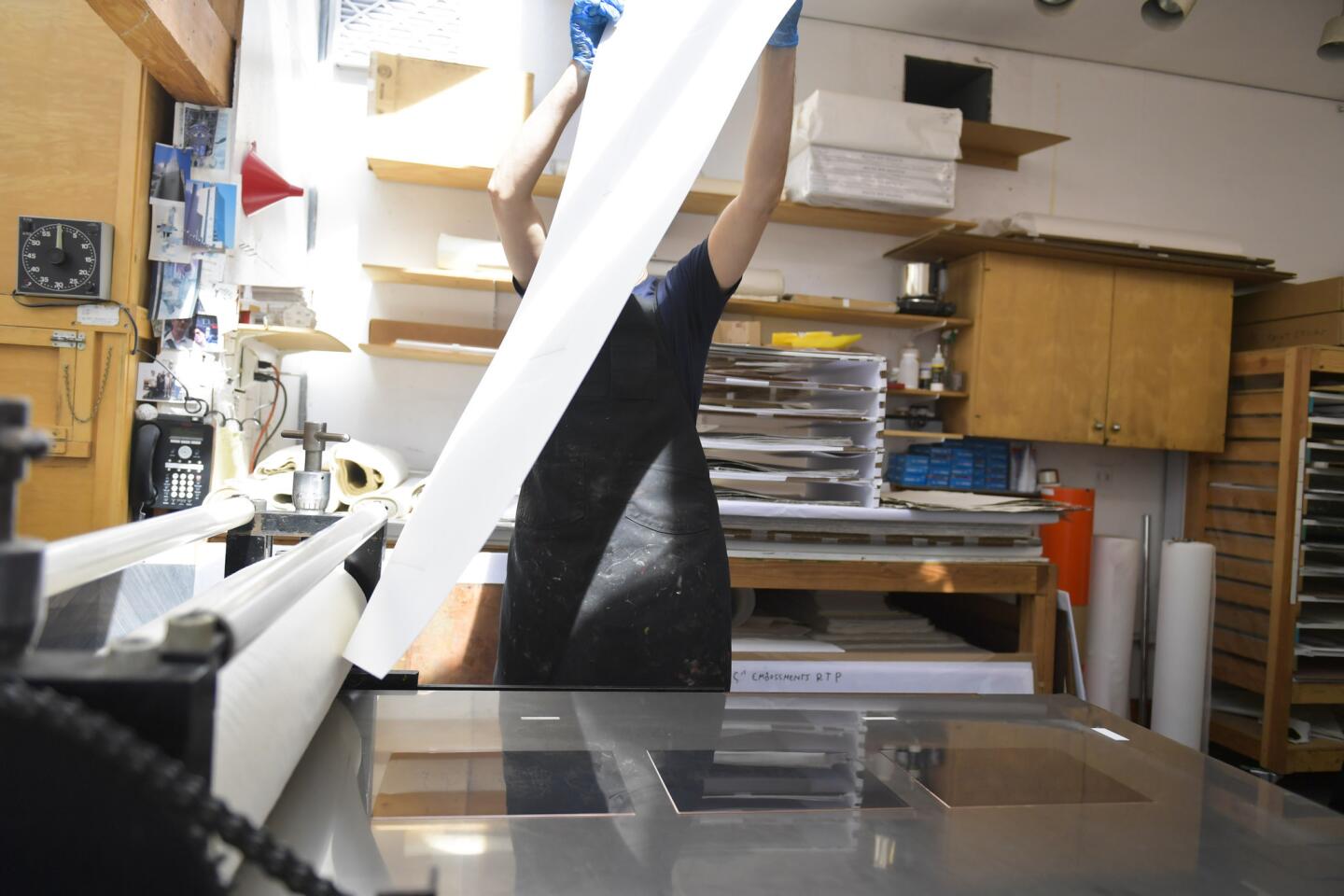

The sour smell of wet ink permeates Gemini G.E.L.’s printing studio, which feels like a time capsule. A master printer works alongside two apprentices, all in dark aprons. They lay out 8-foot sheets of handmade Japanese paper on ginormous steel presses from the mid-1960s, gingerly wiping clean the tabletop edges with cotton cloths. Piles of melted, jet-black paint-stick crayon rest on butcher blocks; glistening canvases wet with ink hang from the walls, drying.

Over the last half-century Robert Rauschenberg, David Hockney, Ellsworth Kelly, Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Frank Stella and Man Ray have produced seminal pieces in modern printmaking at this artists’ workshop and fine art lithography publisher on Melrose Avenue. Today’s work, however, is all about Richard Serra. The printers orbit around one another, creating a series of 12 hand-pulled etchings, “Rift II,” from a parking-lot asphalt rubbing that Serra made.

The rumbling starts up from the machine — a modified lithography press instead of a smaller etching press, to accommodate the artist’s unusually large scale. The Serra work slides through under a felt blanket covered with Plexiglas and 900 pounds of hydraulic pressure. The result is a minimalist, gravelly black surface that the apprentices affix to foam board with stapler guns for inspection. Ink dust, and the pungent sense of art history-in-the-making, linger in the air.

We thought it was gonna be a hobby, that it would be fun to hang around the artists, maybe build up a collection.

— Sidney Felsen

On the occasion of Gemini’s 50th anniversary, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art will open on Sept. 11 a survey exhibition of Gemini works from 1966 to 2014. “The Serial Impulse at Gemini G.E.L.,” organized by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., highlights Gemini’s brazen experimentation, its role in pushing boundaries in printmaking as well as its unusual collaboration between artists and printers.

The exhibit also speaks to Gemini’s role in shaping the nascent L.A. art community of the ’60s and ’70s. Soon after opening in 1966, the workshop — the brainchild of former USC fraternity brothers Sidney Felsen and the late Stanley Grinstein — became a magnet around which artists on both coasts coalesced for creative collaboration, art openings and parties. The momentum helped to fuse a young and geographically disconnected local art scene, and it bridged gaps between East and West Coast artists, fueling the nationwide printmaking revival that coincided with a blooming contemporary art world.

“Gemini helped synthesize the L.A. art world,” says Diana Gaston, director of Tamarind Institute, leading printmaking educators based in Albuquerque. “Gemini re-imagined the possibilities of printmaking. They pushed it into a new scale, working big, a new level of complexity, incorporating new materials. That’s had a longstanding, very far-flung influence on the medium.”

Sitting in his office, where he still manages the business every day, the nearly 92-year-old Felsen is modest about his and Grinstein’s intentions.

“It was innocence,” he says, peering out from under a wide-brimmed straw Panama hat and wire-rimmed glasses. “We thought it was gonna be a hobby, that it would be fun to hang around the artists, maybe build up a collection.”

Felsen leans back in his swivel chair and surveys his small workspace, itself an ode to midcentury printmaking. Flat files house rows of rubber stamps, while card catalog drawers store postal stamps grouped by themes — “birds,” “airplanes,” “dinosaurs.” Colored pencils line the shelves, and the walls are plastered with framed photographs that Felsen shot over the decades. The intimate candids of Gemini artists at work and play offer a prism of art world nostalgia: David Hockney and Dennis Hopper at a western hoedown; Richard Tuttle canceling a printing plate beside his beloved poodle, Coco; Serra hamming it up in a buffalo head costume.

Felsen remembers the exact moment Gemini was birthed: Christmas Eve 1965, at the Grinstein home. Felsen, then an accountant who took painting and ceramics classes at night for fun, and Grinstein, an art collector who was in the business of forklift equipment, invited local printmaker Kenneth Tyler to the party to discuss an idea. Tyler owned a commercial print shop called Gemini Ltd.; artists would bring in their drawings to be converted into prints.

What if, Felsen and Grinstein suggested, they turned the for-hire shop into a creative workshop and publisher of fine art prints, with Tyler as a partner. A small group of invited artists could use the equipment, studio space and art materials for free and work with the shop’s expert printers to create new work. The newly coined Gemini G.E.L. (the latter stands for “graphic editions limited”) would even pay to fly in big-name artists and put them up for weeks in hotels or apartments. Gemini would then exhibit and sell the finished artworks, which they owned the rights to, and split sales with the artists.

The business became a family affair, with Felsen’s then-wife Rosamund Felsen and Grinstein’s wife, Elyse, helping to get things off the ground as co-owners. Often, the two families, kids in tow, would crowd around the Grinstein dining room table to sort advertising brochures.

“We thought, one day we’ll pay someone to do this,” says Ayn Grinstein, who, after Stanley Grinstein died in 2014, has run the business with sister Ellen Grinstein Perliter, Felsen’s wife Joni Weyl, and his daughter, Suzanne Felsen.

No one expected Gemini to take off so quickly.

“I thought I’d be an accountant forever,” Sidney Felsen says. But the company’s first ad, in Artforum in 1966, generated about 300 inquiries, Felsen says. “I hand-delivered the copy to this kid who was laying out the pages. Turns out it was Ed Ruscha, his early beginnings.”

At first Gemini pursued the Abstract Expressionists: Mark Rothko, Hans Hofmann, Willem de Kooning. “But none of them came, they didn’t want to make prints,” Felsen says. Tyler knew the Connecticut-based Josef Albers from L.A.’s Tamarind Lithography Workshop. He agreed to help them get started that first year, producing a series of 16 prints he called “White Line Squares.” Meanwhile, that same year, Man Ray had an exhibition at LACMA, which asked museum supporter Stanley Grinstein to host the artist while he was in town. Ray became intrigued by Gemini. “We were too embarrassed to invite him to work with us,” Felsen recalls. “Finally, he just asked. He did three editions.”

Rauschenberg, however, was the tipping point. In 1967 he wanted to produce “Booster,” a 6-foot-tall self-portrait made from X-rays that would be the largest hand-pulled lithograph in the world at the time. “We thought: ‘OK, we’ll try,’” Felsen says of the seemingly impossible project. Rauschenberg boasted of its success to friends Frank Stella and Claes Oldenburg, “and we were up and running,” Felsen says. In 1968 Oldenburg traveled to L.A. to create Gemini’s first three-dimensional sculpture edition, the groundbreaking “Profile Airflow,” a translucent aqua Chrysler Airflow protruding from a two-color lithograph.

“They completely joined in with what I was doing and we invented things as we went along,” recalls Oldenburg, adding that when he arrived in L.A., Felsen picked him up in a Chrysler Airflow purchased for the artist. “It looked exactly like the car I wanted to make — but maroon with black fenders. I was able to use it while I was there and I could study it!”

Gemini’s willingness to take creative risks and accommodate artists’ whims — building new tools, modifying equipment for projects and, one year, bringing Rauschenberg’s beloved “The Young and the Restless” actors into the studio for inspiration — became hallmarks. L.A. artists Ruscha, Ken Price, Bruce Nauman and Jonathan Borofsky became regulars. The New Yorkers typically visited in winter to escape the cold. Lichtenstein came every other year in February, for decades, Felsen says. Artists typically stayed several weeks, let the printers finish the job and then returned months later to approve and sign final works.

It’s a little intimidating because of the legacy. But it’s inspiring and empowering too.

— Analia Saban on working at Gemini

The Grinsteins threw raucous parties for visiting artists, further boosting the allure and sense of community, recalls John Baldessari, who met Rauschenberg, Oldenburg and Frank Gehry at the Grinstein house.

“They provided a meeting ground for artists from both coasts,” Baldessari says.

Tyler departed in 1973 to start another shop, but the evolution continued at Gemini. In 1976 Gehry, who hung around with the artists, designed an extension to Gemini, which now houses two exhibition galleries open to the public and four studios working between lithography, etching, screen printing and woodblock printing as well as sculpture editions.

In an age of online art appropriation and digital printing, Gemini is a respite of slow art, producing purposefully small, handmade editions sold to collectors, galleries and museums internationally. To date it has produced more than 2,000 works on paper and 300 sculptural editions — but only by about 75 artists over five decades. Selectivity is key, Felsen says, adding that Gemini may take only one or two new artists in any given year.

“We’re busy all the time, but we know the reality: Jasper is 86, Claes is 87, Gehry is 87, Baldessari is 85. They’re not gonna be around forever. You want to invite someone new regularly, but you also want to keep your shop small so you don’t become a mill. Right now it’s like a cathedral.”

Toward that end, Gemini keeps an eye on younger artists. It watched Baldessari’s former student, Analia Saban, for about six years before inviting her last year, along with the more established Tacita Dean.

“It’s a little intimidating because of the legacy,” Saban says of working at Gemini. “But it’s inspiring and empowering too. Because they make you feel like you’re part of that legacy. Like, now it’s my time to make something happen with these tools.”

The LACMA exhibition, which showed at the National Gallery through early February, includes 127 prints from 16 series, all shown in their entirety. The L.A. incarnation of the exhibition, curator Leslie Jones says, is “a remix” highlighting connections between Gemini and LACMA and focusing on works in the museum’s collection. Albers’ “White Line Squares,” which LACMA exhibited in 1966, will be on view along with Lichtenstein’s 1980 “Expressionist Woodcuts,” which were inspired by works the artist viewed at the museum. The exhibition will also present works by Johns, Stella and Oldenburg, among others, and newer work by Julie Mehretu.

“We’re slicing it in a way that brings attention to seriality, which is kind of a unique aspect of Gemini’s production,” Jones says. “But also highlighting these sort of parallel histories [between LACMA and Gemini] that correspond with the rise of the L.A. art world.”

“Serial Impulse” will also underscore collaboration in printmaking, with printers’ names included on artwork labels alongside artists; expanded wall text aims to demystify the printmaking process.

Working here, you feel part of the art. You didn’t make it, but you’re around when it’s born, and you know the artists, and you have a relationship.

— Sidney Felsen

Many of Felsen’s photographs of Gemini artists and printers at work together will also be on view.

“As time went by, we realized more and more what was happening, all these important artists coming through, and I thought, ‘I should document it,’” Felsen says, sitting in his office.

He scans the wall of pictures, his eyes eventually resting on a black-and-white photograph of young Rauschenberg leaping onto a bicycle in Gemini’s parking lot.

“Working here, you feel part of the art,” he says. “You didn’t make it, but you’re around when it’s born, and you know the artists, and you have a relationship. Looking back, I feel part of something.”

Follow me on Twitter: @DebVankin

ALSO

LACMA acquires 39 major works produced at Gemini G.E.L.

Arts patron and Gemini G.E.L. co-founder Elyse Grinstein dies at 87

Art world A-listers celebrate the woman who brought them together — and put L.A. on the map

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.