Column: Why the Expo Line to Santa Monica marks a rare kind of progress in American cities

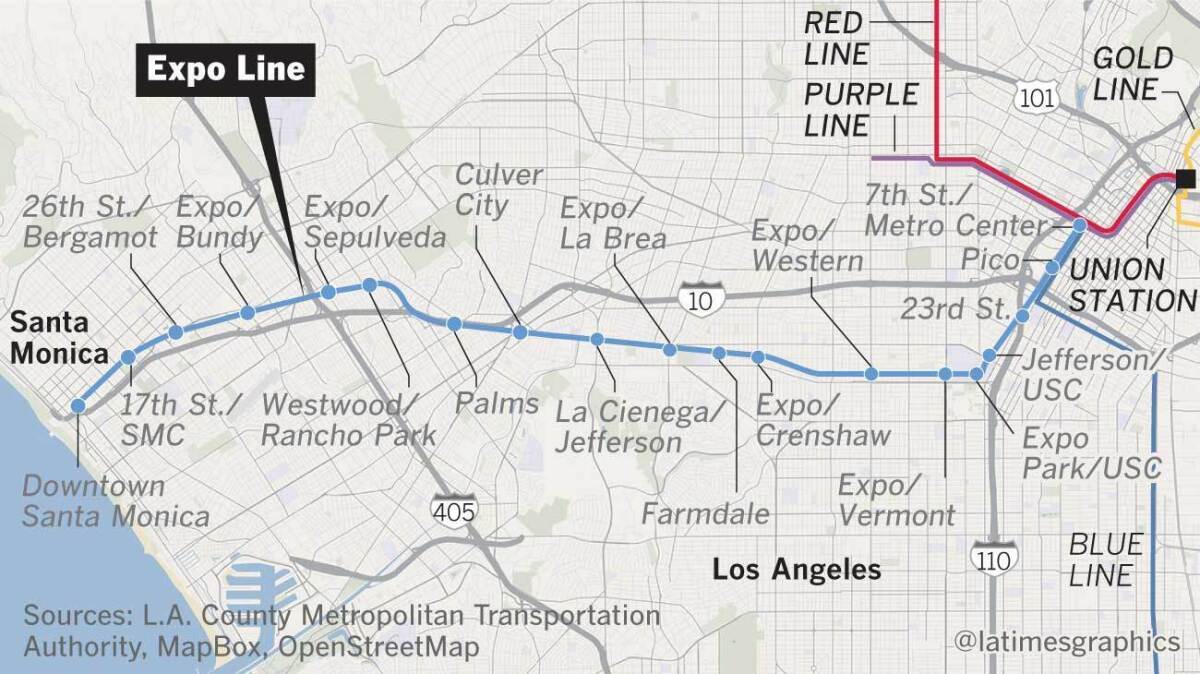

The $1.5-billion second leg of the Expo Line, which opened Friday from Culver City to Santa Monica, adds seven light-rail stations and more than six miles of track to the growing Los Angeles County transit network. That’s on top of the six stations and 11.5 miles that came on line when the Gold Line extension, connecting Pasadena with Azusa, opened in March.

In the immediate context of L.A.'s attempts to turn its public-transit network from national punch line to something that increasingly resembles a mature system, 13 new Metro stations in less than three months qualifies as a pretty dramatic upgrade. (New York City has added exactly one subway station over the last 25 years, the Bay Area’s BART system fewer than a dozen stations over the last four decades.) The investment county voters made in approving the Measure R sales-tax hike in 2008 is showing dividends for the first time — and suggesting some progress in chipping away at the dominance of the car.

But if you step back and take a longer historical view, one that acknowledges that Los Angeles didn’t just exist but in many ways fundamentally shaped and defined itself before the rise of the freeway system, the new rail routes begin to take on a different character. Their arrival is part of a larger restoration, an attempt to dust off and build on a long-buried transit history that makes up much of the basic DNA of L.A. urbanism. That effort, for all its incompleteness and halting progress over the last three decades, is by the standards of American urban history unprecedented in scope.

FULL COVERAGE: Metro Expo Line opens to Santa Monica

The Gold Line extension to Azusa was built along the former Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe right of way, which Metro bought in the early 1990s. The Expo Line uses a right of way that from 1908 to 1953 was part of the Pacific Electric Red Car’s Air Line service from downtown to the beach.

The gaps left behind when those lines stopped running after World War II are the spaces in which the Metro expansion has found its most valuable room to run. What the Gold Line and Expo Line extensions represent is not so much progress in the traditional civic sense — infrastructure that we’ve taxed ourselves to build from scratch — as a long-delayed effort to make the transportation map of the region whole again.

It’s easy to overlook that history in the rush of commentary about what the Metro expansion means and how Angelenos have greeted it. Los Angeles remains an amnesiac city in many ways, or at least one with a very short civic memory. The idea of moving ahead by repairing or revisiting the planning missteps of many decades ago is one we have trouble taking seriously.

The reception to the Gold and Expo Line extensions, opening as they are in the shadow of a major transit-tax measure headed for the November ballot, has been heavily influenced by this kind of thinking. The L.A. conventional wisdom still demands that every advance in public transit infrastructure be judged primarily — and sometimes exclusively — by the effect it has on drivers and its relationship to car culture, what the critic Reyner Banham called our "Autopia." Metro doesn’t help matters with its billboards proclaiming that new lines “ease traffic.”

The idea of moving ahead by repairing or revisiting the planning missteps of many decades ago is one we have trouble taking seriously.

The result? Instead of seeing the light-rail extensions as part of a slow but significant effort to close that historical loop (while opening new ways for current and future Angelenos to move around the region), we see them in terms of the vexing challenges they present for the driving public.

“So how do I get to the station?” 64-year-old Pacific Palisades resident Liesel Friedreich asked my colleague Laura J. Nelson after learning there is no dedicated parking structure at the Expo Line’s new station in downtown Santa Monica. “Isn't the point to get more people with more money to ride the train?”

It’s not as though there is any shortage of parking near the station in downtown Santa Monica. Does Ms. Friedreich — do you? — know how many garages and surface lots the city of Santa Monica operates within a 15-minute walk of that station?

Maybe you’d guess three parking structures, or four.

The answer is 16, by my count, holding more than 8,000 spaces. (Within an easier five-minute walk the number is a still-quite-healthy 3,000-plus spots; widen the circle to a 20-minute walk and the total approaches 10,000.) There are also privately run garages and surface lots near the station, to say nothing of street parking and valet services at Santa Monica Place and hotels.

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour >>

It’s possible that the Expo Line’s stop in downtown Santa Monica has as much city-operated parking within walking distance as any light-rail station in the country.

Yet there is apparently no shortage of Angelenos ready to fault Metro for not building more, or who expect that all the parking near the new stations be free or very cheap, as a kind of regional subsidy for the continuing fiction that there are no public costs associated with driving.

You might as well ask of the 101 Freeway why it links up so poorly with the Metrolink to Covina.

Demand for parking is expected to fall markedly in coming years with the rise of car sharing and driverless vehicles. Every parking structure directly connected (with an ease for drivers bordering on the umbilical) to a Metro station that we build now is one that we may well be spending public money to tear out or turn into something else two or three decades from now.

There’s also the larger point that land controlled by Metro along transit corridors would be much more productively used to address the region’s chronic shortage of affordable housing.

The continuing expectation that the car eat first in Los Angeles has already affected the Expo Line. Its first phase moves more slowly than the new leg because much of it runs at street level, leaving trains to wait for intersections to clear of cars.

Still, to the extent that we can pry ourselves from conversations about what the Metro expansion means for car culture, there is the urban design of the new routes to consider: not just the architecture of the individual stations but the bike paths, landscaped corridors and civic plazas that surround or run along the routes.

The stations on the Expo Line extension, with their wavy canopies and concrete-and-polished-metal palette, match those on the first leg, which connects downtown with Culver City and opened in 2012. They were designed primarily by Roland Genick, chief architect for rail and transit systems at Parsons Brinckerhoff.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

May 23, 9:56 p.m.: Roland Genick is an employee of Parsons, not Parsons Brinckerhoff.

------------

The new Gold Line stations (also designed by a team at Parsons) have a similarly consistent if underwhelming architecture following a vaguely Spanish theme, their pitched-roof canopies topped with scored faux tile.

In both cases the stations win at least modest points for simplicity and consistency — an encouraging change from the way Metro used to roll out new lines, with a different designer for each station and a taste for overwrought populism. When the Crenshaw Line and Regional Connector open (by 2020) we’ll finally see the debut of Metro’s new stripped-down and essentially Modernist “kit of parts” station architecture, developed with L.A. firm Johnson Fain.

The way the new lines meet the urban fabric also suggests an imperfect sort of progress, a step in the direction of a more enlightened approach.

Mercifully the Gold Line tracks leave the median of the 210 Freeway as trains move east of Pasadena. (At some point Metro will need to confront the fact that the disastrous Lake, Allen and Sierra Madre Villa stations, which maroon everyone waiting for a train on a narrow strip of concrete as freeway traffic rushes by on both sides, will have to be redesigned or at the very least glassed in.) In Arcadia the Gold Line stop even finds room to open onto a simple, well designed public plaza.

The Expo Line extension features a bike and pedestrian path for much of its length, though there's a gap in the path between the Palms station and Overland Avenue, in part because the train travels for that stretch in a trench.

Santa Monica has been especially active in redesigning the areas around the new stations. It got a bike-share program up and running last fall. Between the final Expo Line station and Santa Monica Pier, the city has widened sidewalks and redesigned intersections in anticipation of growing pedestrian traffic.

Some kinks remain: If you want to walk east from the downtown Santa Monica station you have to exit toward the beach and double back. But on the whole the connections between Metro rail lines and city are showing signs of improvement.

The challenges posed by dealing with those connections suggest one key difference between the first generation of commuter rail in Los Angeles and the network we are building now.

Many early Red Car routes ran from one speculative subdivision to another, across a landscape that was largely empty, a civic map waiting to be filled in. The new Metro lines travel through a region that is heavily developed and consistently dense (if still largely low-slung), which makes redesigning the urban context around them difficult and expensive.

This is the price we’ve paid not just for watching the Red Car network die a slow death in the decades before and after World War II but also for dragging our feet in expanding the nascent Metro system in the 1980s and 1990s.

Those older train lines helped shape the region and its buildings. The ones we’re adding now are shaped — and in many cases warped or slowed — by them.

MORE

The Expo Line is finally coming to the Westside, but limited parking raises concerns

Will Santa Monica's Expo Line get you out of your car?

French landscape firm wins Pershing Square competition with call for 'radical flatness'

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.