Autry museum’s ‘Route 66’ exhibit drives influence of the road home

The postcard image is ingrained in our collective consciousness: An empty road cuts through the Mojave Desert, its inky black path stretching forward, seemingly to infinity. A lonely white signpost flanks the asphalt — “Route 66.”

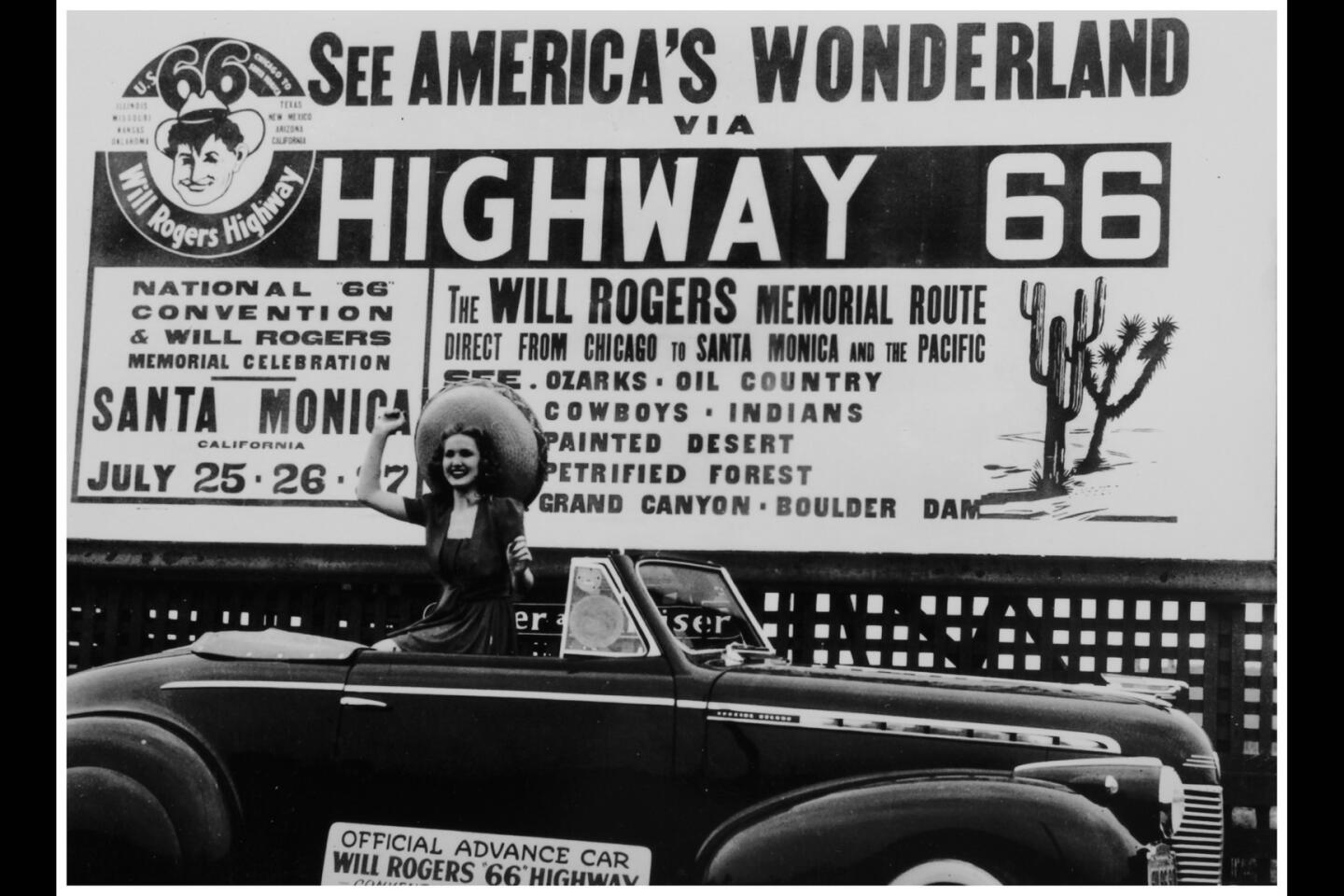

Perhaps more than any other road in America, Route 66 is layered with history and brimming with nostalgia, a post-World War II symbol of possibility and progress that has infiltrated contemporary pop culture as an emblem of the freedoms of the open road. But America’s Main Street, which winds its way from Chicago to Los Angeles, also has a dark side. It was, in its earlier days, a corridor of racism and segregation and the focal point of political contention, such as in the mid-1950s when the interstate highway system emerged.

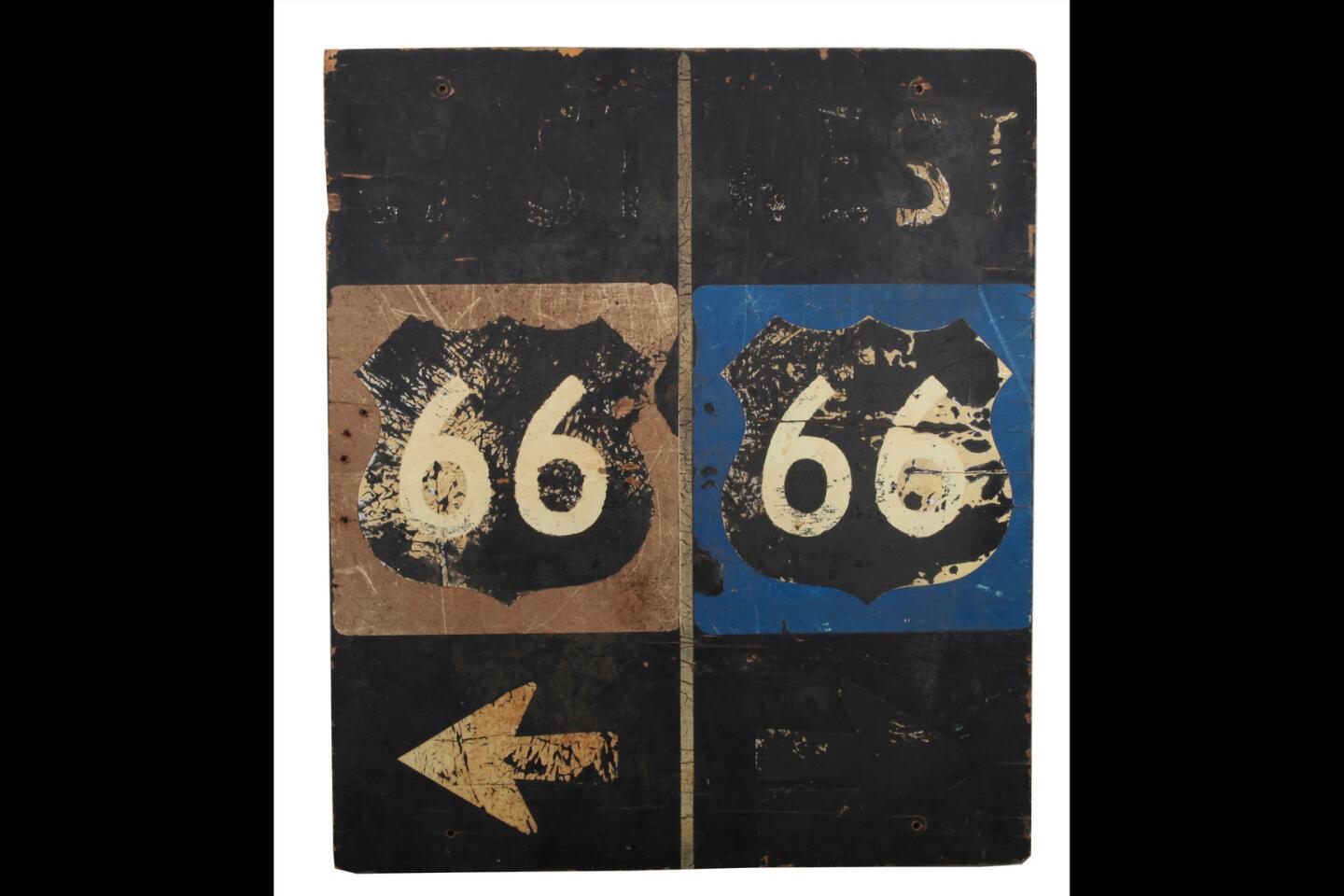

A new show at the Autry National Center of the American West travels those 2,400 miles of open road to tell the story of America on the go in the 20th century. “Route 66: The Road and the Romance” is not just for travel buffs and Americana enthusiasts, however. The exhibit of more than 250 historical artifacts — vintage gas pumps, neon motel signs, John Steinbeck’s original handwritten manuscript of “The Grapes of Wrath” — is particularly issues-driven, aiming to contextualize the American history that unfolded along Route 66 since its inception in 1926.

“We use the highway as a way to examine some much larger issues of 20th century America — class, race, politics,” says Jeffrey Richardson, the museum’s curator of Western history, popular culture and firearms, who curated the exhibit with project advisor Jim Farber. “Nostalgia is a very small part of the exhibition; it’s not a travelogue by any means.”

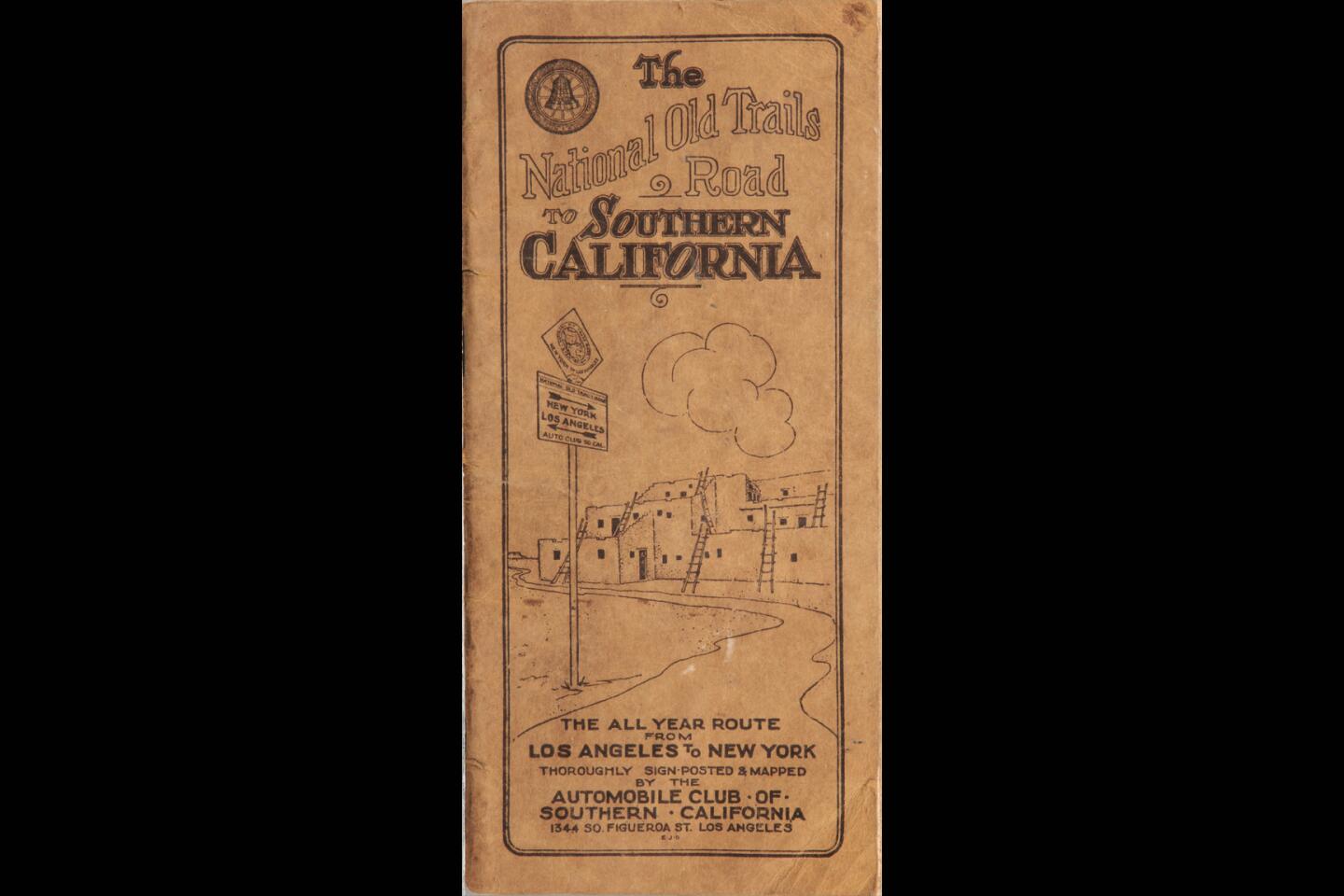

The exhibit, which runs through Jan. 4, is divided into four chronological sections, starting with early transcontinental transportation, the invention of automobiles and the creation of Route 66. The second section looks at the route during the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression, an era when Steinbeck called the road, which had become a migration path West, “the mother road, the road of flight.” Section 3 explores postwar car culture, and it ends with the decline and ultimate revitalization of Route 66.

There’s no shortage of memorabilia crowding museums and tourist outposts in the eight states the road cuts through, including the California Route 66 Museum in Victorville and the Smithsonian’s permanent “On the Road” exhibition. But the Autry exhibit, Richardson says, is unique in its scope as it includes rare artifacts and considers the route from a national perspective. The historical anecdotes, carefully juxtaposed, create dualities that give the show depth.

Songwriter Bobby Troup, for example, who was white, may have gotten his kicks on Route 66 when he penned those idyllic song lyrics in 1946 — and museum visitors can sample the song and the whimsy it conjures, at listening stations. But Nat King Cole’s trio of performers, who recorded it, would likely have had a very different experience traveling the route, which at the time was studded with “sundown towns” that were unsafe for African Americans after dark.

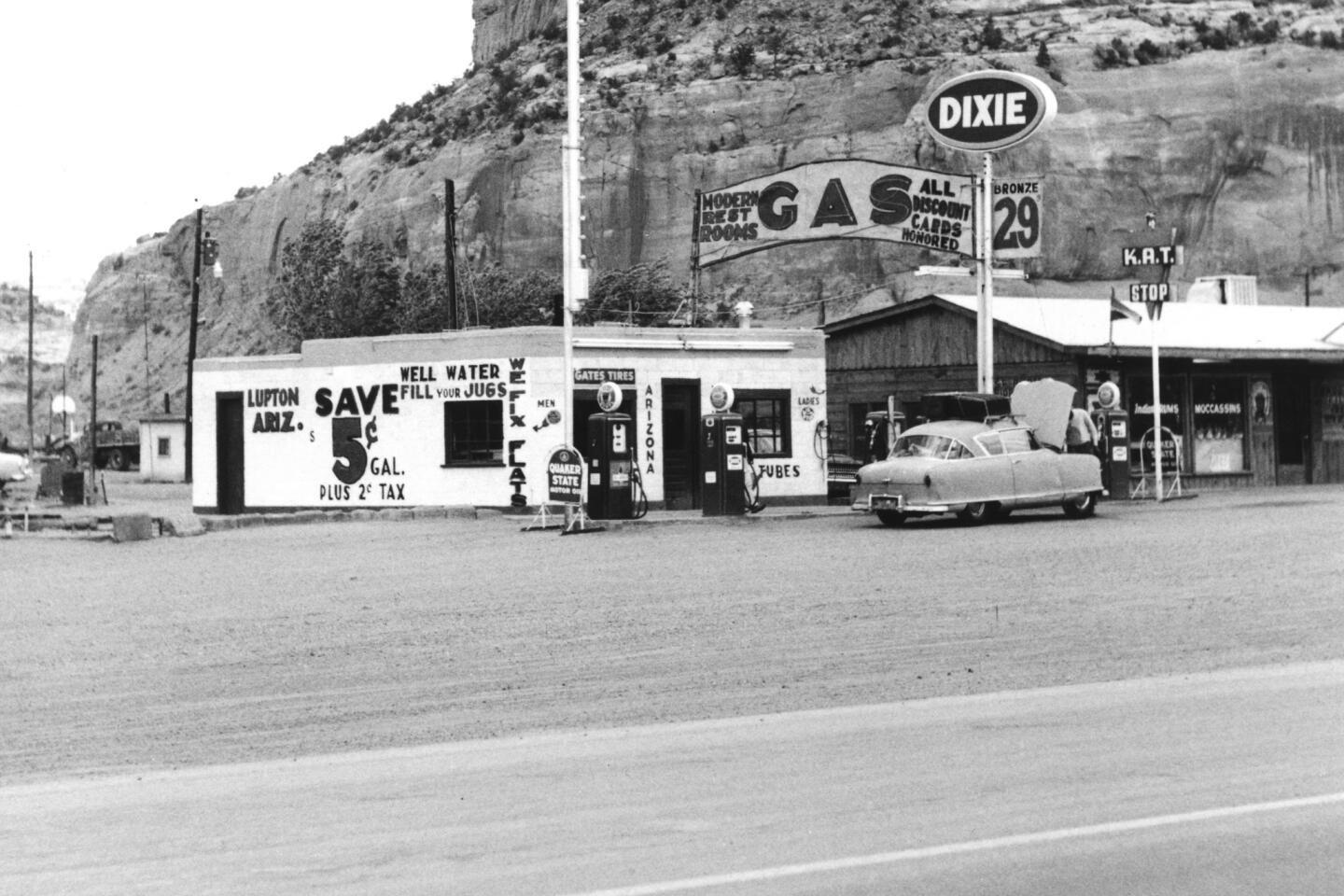

There are six Ed Ruscha photographs on view from the L.A. artist’s “Twentysix Gasoline Stations” series — all stark, black-and-white portraits of gleaming service stations along Route 66. On display with the artworks are photographs of the same locations, taken 30 years later by New York artist Jeff Brouws. In every one of the later images, the gas station has been abandoned.

“We use these images to talk about the impact of the interstate highway system in 1956,” Richardson says, “and the bypassing of so many communities and the impact that had.”

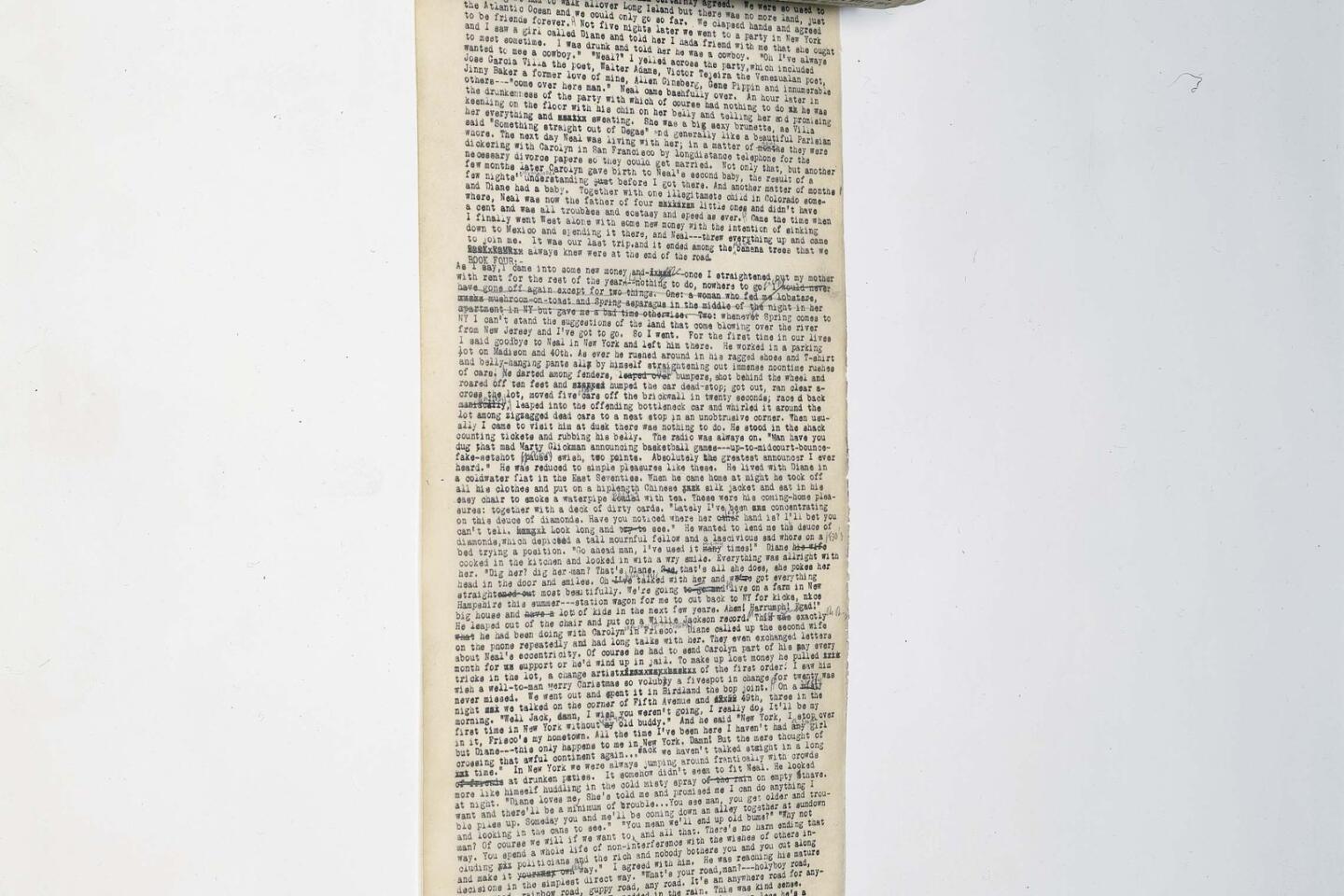

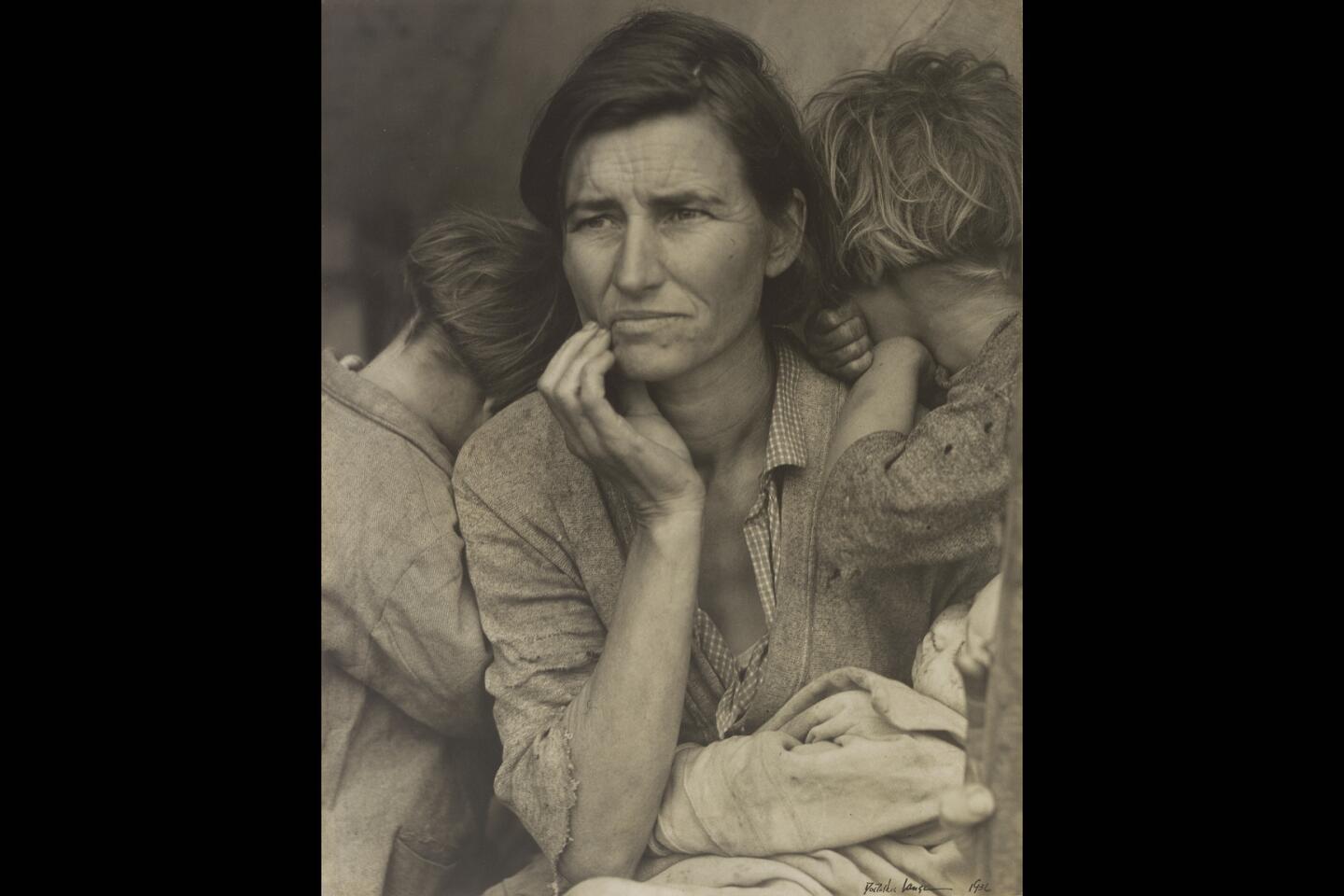

“Route 66: The Road and the Romance” was six years in the making. The Autry made a wish list, says Richardson, of the single best objects it hoped to procure to illustrate individual points, then it set about chasing down those items from private collectors, universities, libraries and other museums. The Autry managed to scratch off nearly every item on the list. Of the 250-plus artifacts in the show, more than 200 are on loan. Among them: the oldest-known Route 66 map, Dorothea Lange’s Depression-era photo “Migrant Mother,” a cream-colored 1960s Chevrolet Corvette and Jack Kerouac’s 120-foot “On the Road” scroll, which visitors can flip through via iPad.

“We went just about anywhere we could to find the most important artifacts to tell this story,” Richardson says.

A social media campaign had two Autry employees driving Route 66 from L.A. to Chicago, taking pictures and interviewing people along the way and gathering materials so visitors can plan their own road trips.

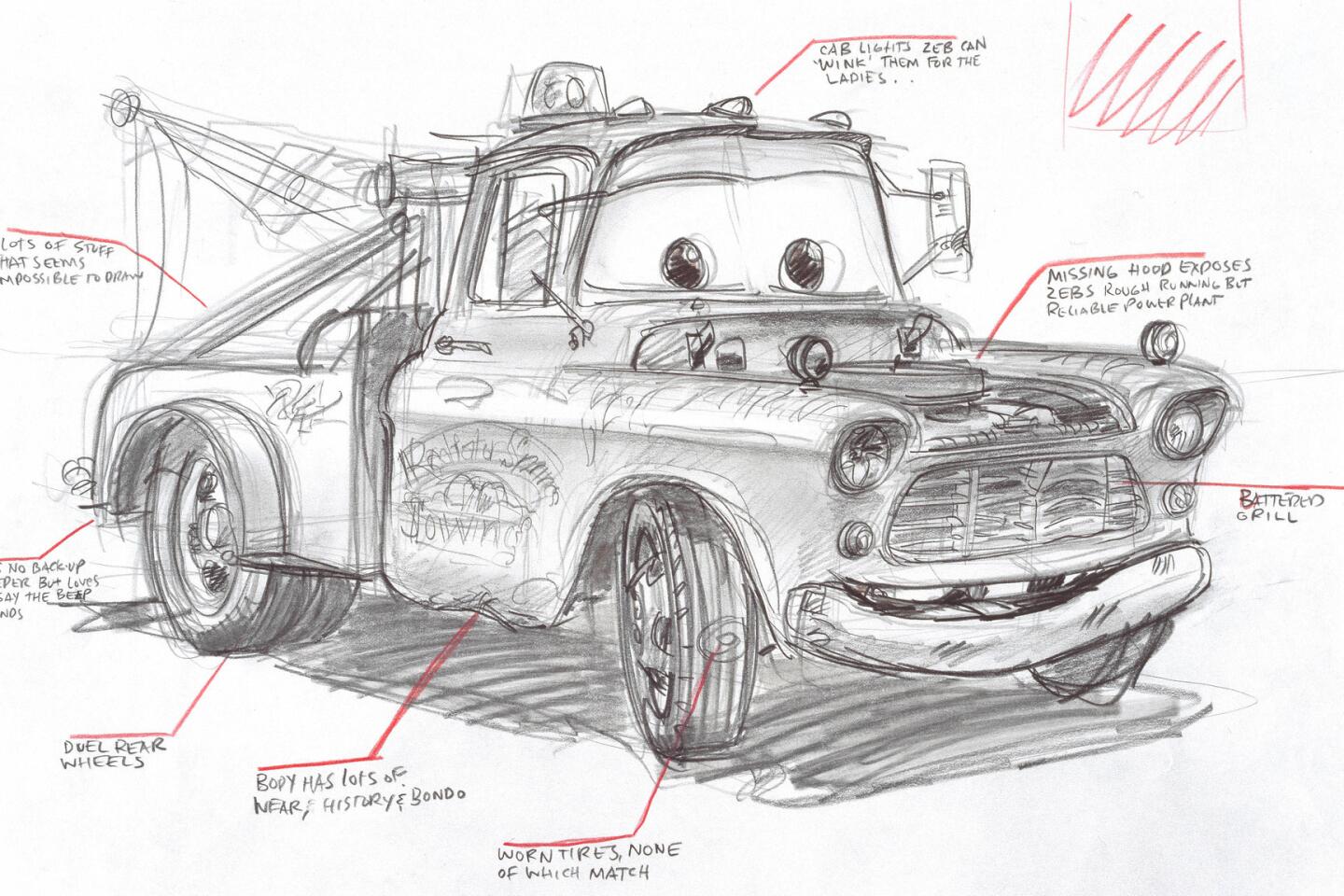

It is the individual, hard-to-come-by objects, however — the literal and fictitious detritus of the road, such as the early Jackson Pollock painting, “Going West,” storyboards and sketches from the animated Pixar film “Cars,” and a chunk of Route 66 asphalt — that Richardson feels will stick with visitors.

“I’d love people to come out of here understanding why Route 66 is called the Main Street of America,” he says. “But the artifacts we’ve chosen are so powerful, these are the things people will be talking about — not just when they leave the museum, but that night, the next day, the next month.”

Twitter: @debvankin

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.