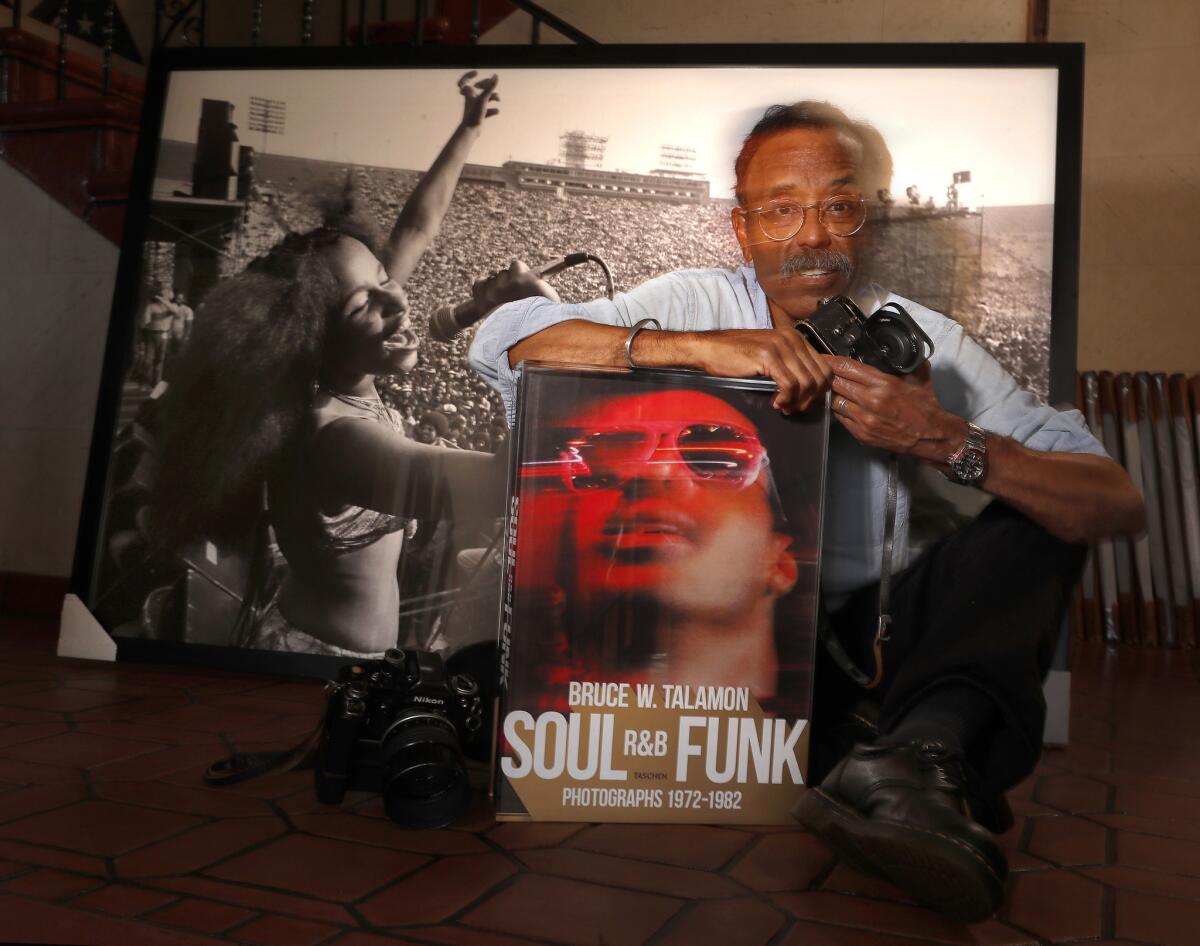

Photographer Bruce Talamon captured black joy in the glory years of soul and funk. Now he’s getting his due

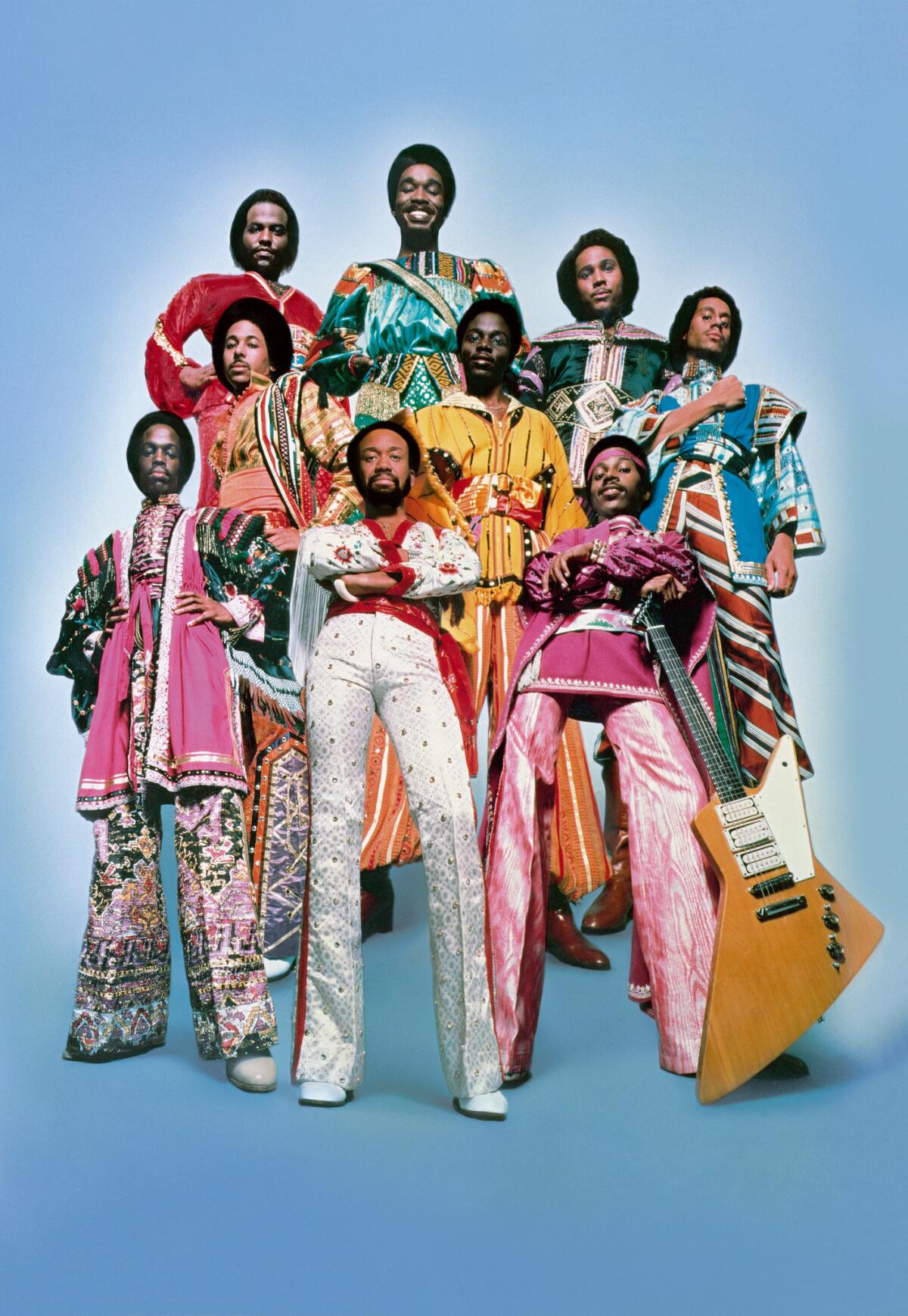

Earth, Wind & Fire founder Maurice White had one name in mind for his memoir photos: Bruce Talamon. The photographer, who has nearly 40 years experience shooting feature film stills, began his career documenting R&B, soul and funk music’s golden age in the 1970s.

In 1979 and 1980, Talamon traveled with Earth, Wind & Fire, capturing shows, rehearsals and moments in between as the band toured Europe, Japan, South America and Egypt. That’s where Talamon took White’s favorite shot, a black and white photo of the musician walking toward the pyramids of Giza.

Herb Powell, who was helping to write the memoir, looked through Talamon’s pictures of the famed funk band and asked the question: “What else you got?”

A light bulb went off. Talamon began to reflect on his collection of images — of Teddy Pendergrass, Stevie Wonder, Diana Ross and many, many more — from the era. It was this eureka moment that led Talamon and his agent to pitch art-book publishers in New York. But they all passed.

Eventually, Talamon took matters into his own hands, writing a provocative letter to publisher Benedikt Taschen in 2015.

Photo books have documented jazz, rock ’n’ roll, the Rolling Stones. But there’s never been a photo book on R&B, soul and funk music, Talamon said. “As far as I’m concerned, that’s criminal. That speaks to being marginalized as the music was back then.”

Talamon usually was the only black photographer on the West Coast consistently photographing R&B, soul and funk musicians, he said.

"Generally, white photographers showed up at the white acts — Paul McCartney, Led Zeppelin, the Stones," he said. "They might do the Jackson 5 and Diana Ross and Marvin Gaye and Smokey [Robinson], but they weren’t going to do Thelma Houston. They weren’t going to do Ashford & Simpson because there was no market for it."

To Talamon’s surprise, a representative from Taschen wrote back within a day, and weeks later an editor was in his living room poring over more than 5,000 early-career photos.

“Here I was revisiting this stuff some 40 years later, and it jumped out at me — the Parliament-Funkadelic group shot, the stuff with Bill Whitten,” Talamon said, referring to the designer of stage costumes for the Commodores, the Jacksons and others. “One of the things I said to my editor: I definitely did not want this book to be just some black guys screaming into a microphone. I had no interest in that, because this is about so much more.”

“Bruce W. Talamon. Soul. R&B. Funk. Photographs 1972-1982,” released this fall, features nearly 300 images chronicling the performers and the fans from the era. Talamon’s book highlights not only the icons — including Franklin, Wonder, Summer and the Jackson 5 — but also showcases influential acts that didn’t find the same mainstream success, such as the Stylistics or the Dramatics. Also documented are cultural touchstones such as Don Cornelius’ music and dance TV program “Soul Train.”

A 1978 shot catches Marvin Gaye and his brother eating Thanksgiving leftovers at their mother’s home on South Gramercy Place in L.A. Patti Labelle props up her heels after a long day of interviews and radio-station visits in 1977. Quincy Jones is at the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco working on music arrangements with his then-wife, Peggy Lipton.

Sitting in his South L.A. home, Talamon flipped through the nearly 10-pound tome on his lap and reflected on how those early photos affected his career, which has included work for magazines and for filmmakers like Steven Spielberg.

“So many visual artists don’t get recognized until they’re either dead or in a wheelchair,” he said. “It’s nice to get this recognition.”

“I definitely did not want this book to be just some black guys screaming into a microphone. I had no interest in that, because this is about so much more.”

— Bruce Talamon

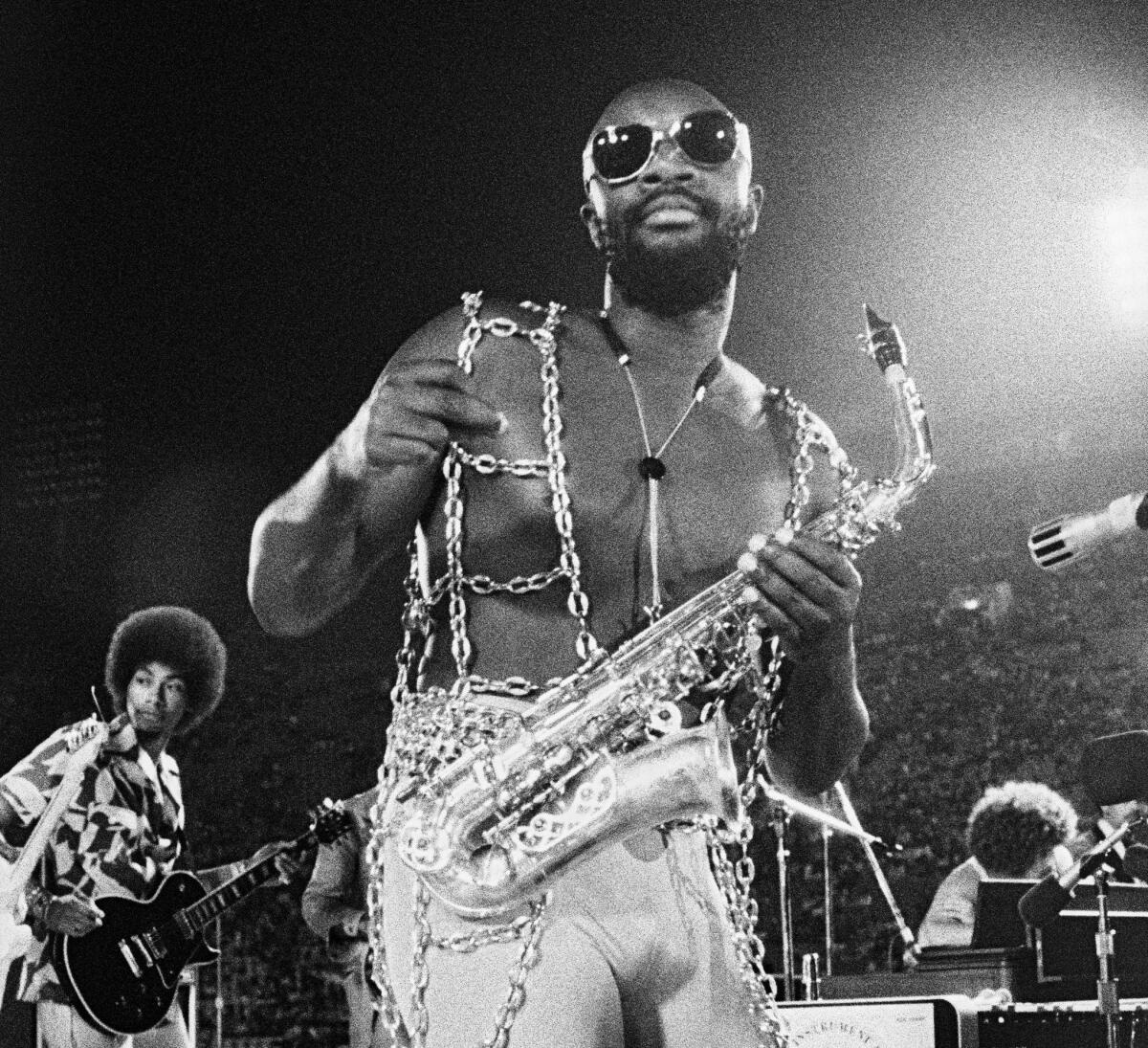

Wattstax, 1972

Born and raised in South L.A, Talamon never planned on becoming a photographer. As a political science major at Whittier College, he aspired to pursue law.

During a semester abroad, Talamon purchased his first camera, a Pentax Spotmatic, for $100 in Berlin. “Then I read the directions and started photographing,” he said. After learning that Miles Davis would be performing at the Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen, Talamon bought cheap seats to see the jazz artist. But he also wanted to take photos.

Camera in hand, Talamon headed toward the front of the stage.

“The usher said, ‘You have to go back to your seat, sir,’ ” Talamon recalled. “And I said … ‘Well, I’m a photojournalist from Jet magazine.’ ” The lie allowed him to snap some of his first music shots.

After graduating college, Talamon moved back to L.A. to pursue photography as a career.

In 1972, Talamon secured a photo pass to Wattstax, a benefit concert at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum held seven years after the Watts Riots. Dubbed “Black Woodstock,” the concert included the Staple Singers, Albert King and the Bar-Kays. Then 23, Talamon captured his first R&B photograph: soul singer-songwriter Isaac Hayes wearing aviators and wrapped in chains that draped from his shoulders to the stage.

The concert is also where Talamon met one of the most influential people in his career, Howard Bingham, Muhammad Ali’s photographer.

Soul newspaper 1972-82

That year Bingham introduced Talamon to Regina Jones, the publisher and co-founder of Soul Newspaper, a publication born out of the Watts Riots and focused on black entertainers. His first cover assignment for Soul was photographing “Me and Mrs. Jones” singer Billy Paul at an obscure nightclub in the Crenshaw district.

"It was packed full of women, from young women in there, old sisters in there, shaking it up to ‘Me and Mrs. Jones,’ " Talamon recalled. "It was wild up in there. The drinks were flowing."

After a couple of months freelancing for Soul, Jones sent Talamon on a press junket to Japan and Hong Kong with Motown Records’ premier female singing group, the Supremes.

It was there that he caught the attention of Bob Jones, a prominent black publicist who worked for Motown. Talamon said that for Jones it was important to hire black photographers. And in an era when black music was also a political statement, artists began speaking up too. "They understood the power of their positions," Talamon said. “Black acts were asking stuff like, ‘Where are the black photographers?’ ”

Motown became his first corporate client and led to more gigs with record companies shooting publicity and editorial photographs.

At Soul, Talamon photographed what he called R&B royalty: Pendergrass, George Clinton and Smokey Robinson. Oftentimes, the newspaper featured artists before they hit the mainstream.

“This woman allowed us to experiment, to have fun,” Talamon said of Jones. “She knew we would come back with something good.”

“He never stopped trying to improve himself,” Jones said. “Bruce was always trying to come up with a better picture, a better lighting, a better staging, better concert shooting. … He was always looking to be better and make the publication better.”

Combing through Talamon’s book was an emotional experience.

“We were all too busy moving so fast with very, very, small staffing to low to no budget,” Jones said. “You’ve got a deadline every two weeks and then on to the next issue. You didn't get to sit there and look at [the photos].”

And all these years later, she said, the work is proving even more important.

“There’s no other book I’ve ever seen out there … that covers intensely the way he does the black recording artists of the era,” Jones said. “I don't think there’s anything like it.”

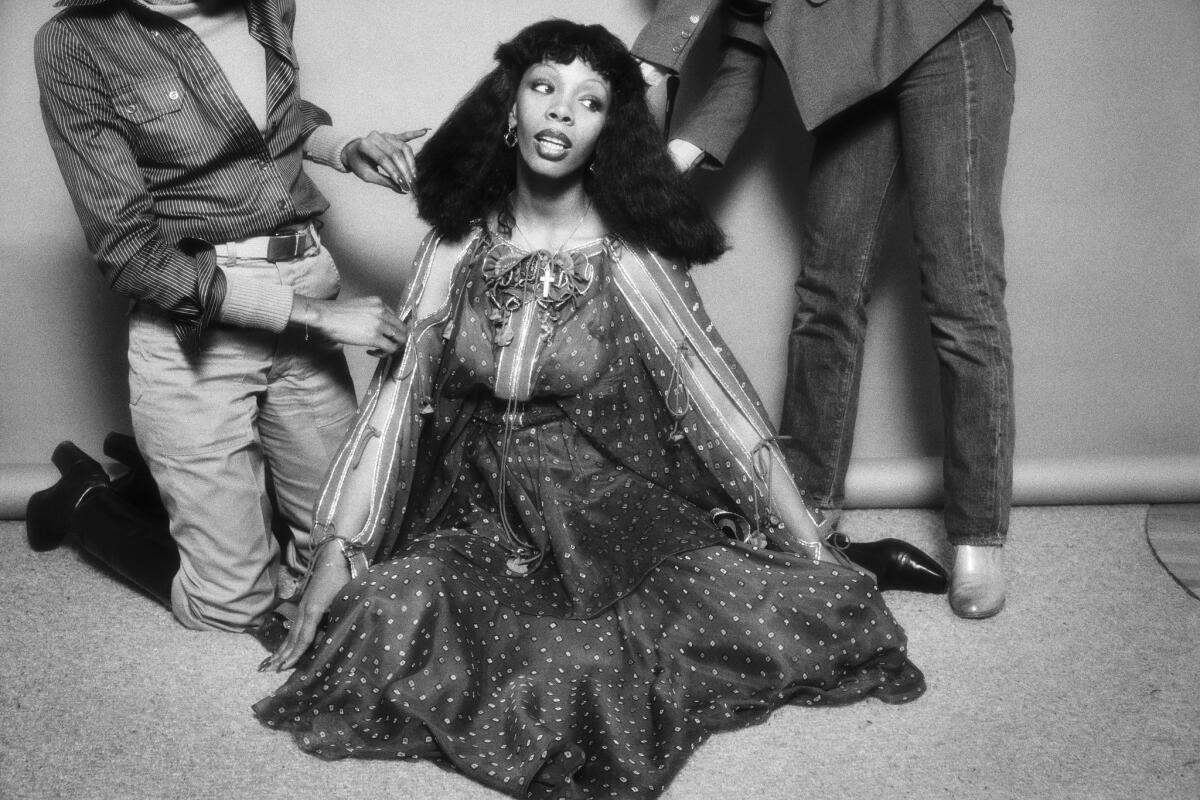

Donna Summer, 1977

After convincing Jones to invest in strobe lights to improve Soul’s covers, Talamon used the new equipment in sessions with Summer, Bootsy Collins and Chaka Khan and her band Rufus.

He referred to Summer’s shoot as one of the most important in his career.

In 1977, Summer was scheduled for 20 minutes, but when the queen of disco saw the sophistication of the setup by Talamon and his partner Bobby Holland, she stayed for four hours.

Months later, Summer told Ebony magazine that she had worked with Talamon, and the shoot became his first national magazine cover. That year he also shot comedian Richard Pryor for People magazine.

Importance of the Leica

As a self-taught photographer, Talamon credited those who helped him throughout his career. He learned to light from Holland and Jim Britt, a staff photographer for Motown. He also counts Hollywood portrait photographer Bob Willoughby and rock ’n’roll photographer Jim Marshall among his teachers.

“Bruce put a stop to the going to law school, but Bruce didn’t put a stop to learning,” said Talamon, referring to himself in the third person. “I took the tools that I learned as a political science and sociology major and I applied them to photography.”

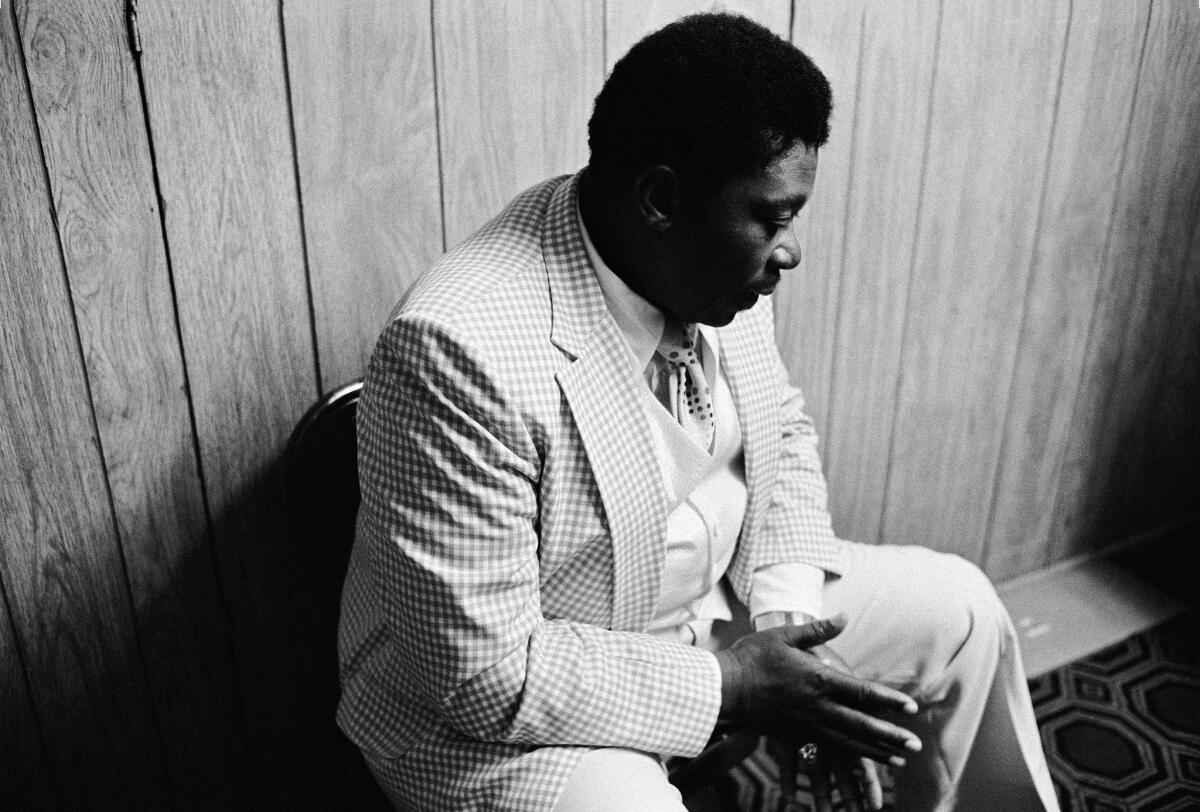

One tip he learned from Marshall was to use a Leica in quiet moments. Holding the camera in his hands, Talamon demonstrated the faint click of the shutter.

This was the camera he used to photograph B.B. King waiting backstage at the Roxy in 1978. It was the camera he used in 1984 while covering Jesse Jackson’s historic presidential run for Time magazine. Talamon used the Leica during Jackson’s apology at a New Hampshire synagogue for using a derogatory term to describe Jewish people in an interview.

“I took off all my Nikons, put my black and white in my pocket and walked up to them and said, ‘I need to be there,’ ” Talamon said. “He let me come in.”

Nearly 30 years later, after switching to digital cameras, he brought the Leica to set while working on the 2011 romantic comedy “Larry Crowne” and snapped black and white personal photos for Tom Hanks and Julia Roberts.

Then and now

Talamon lamented the tight control that publicists and music labels yield over an artist’s image now. In the 1970s, the photographer was often given unlimited access. “You were creating something, and you were photographing and you were watching,” he said. “You can’t do that in five minutes; you can’t do that in three songs.”

“No publicist is going to use this,” he said, referring to the book’s cover, a blurred shot of Stevie Wonder performing at Inglewood’s Forum in 1980. “This was me having some fun after I’d gotten the shot.”

But all these years later, Talamon also noted the connections between performers of the past and newcomers today. “One of the things I wanted to show was how much these musicians have to give,” Talamon said. “Now that is something that is consistent with today.”

“That’s why I have that picture of Al Green collapsed at the door of his dressing room. … He left it all out on the stage. And that’s what they would do, the Isley Brothers, B.B. King, James Brown — when they said they were the hardest working men in show business, that’s the truth.”

MORE ARTS

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.