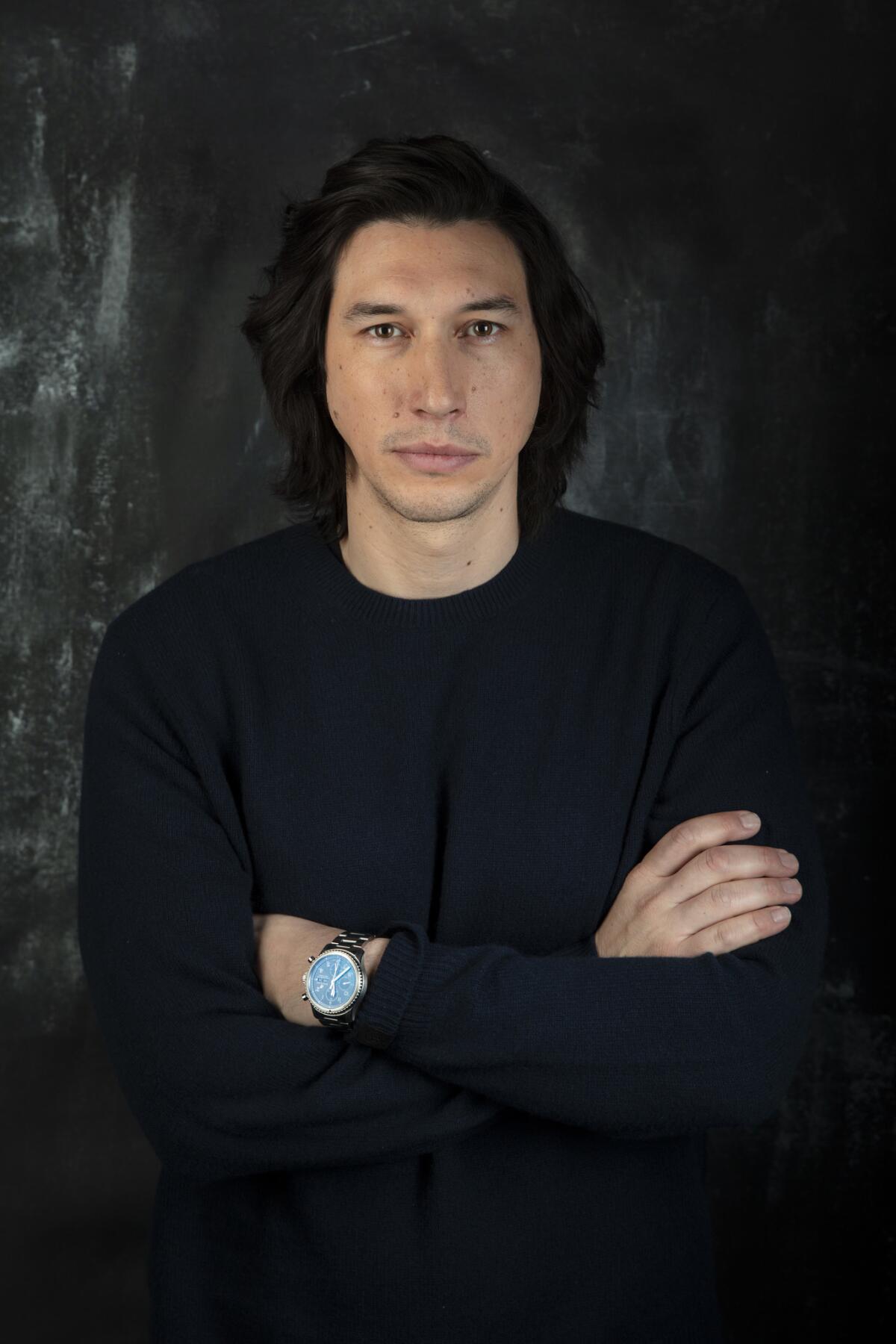

Adam Driver talks ‘Burn This,’ uncomfortable theater and why ‘self-doubt is where I live’

Reporting from New York — Before Adam Driver opened “Burn This” on Broadway on Tuesday night, he had earned his first Oscar nomination for Spike Lee’s “BlacKkKlansman.” He also had devotees from his Emmy-nominated role in the HBO series “Girls,” plus another set of fans who knew him as Kylo Ren, the dark-side son of Han Solo and Princess Leia in the “Star Wars” movies.

In other words, Driver, 35, is hard to pin down or pigeonhole.

The former Marine and Juilliard graduate shifts easily, playing charming and selfish or quietly reserved or endearingly goofy or smug and temperamental. Top directors across generations have noticed: Driver has worked with Clint Eastwood (“J. Edgar”), Martin Scorsese (“Silence”), Steven Spielberg (“Lincoln”), Jim Jarmusch (“Paterson”), the Coen brothers (“Inside Llewyn Davis”), Steven Soderbergh (“Logan Lucky”) and Noah Baumbach (multiple movies, most recently “The Meyerowitz Stories”).

Even in a smaller role in a lesser movie, like the 2013 Daniel Radcliffe-Zoe Kazan rom-com “What If,” he provides startling moments, like the scene where he memorably declares, “I just had sex. I’m about to eat nachos. It’s the greatest moment of my life.”

Now Driver has returned to Broadway for the first time since “Man and Boy” with Frank Langella eight years ago, this time in a revival of Lanford Wilson’s 1987 play. In “Burn This,” Driver is the desperate, distraught and volcanic Pale, holding his own against the memory of the scenery-chewing performance made famous three decades ago by John Malkovich. Considering that Pale’s passion and temper are similar to Kylo Ren’s, it’s an interesting coincidence that looming over the marquee featuring Driver and costar Keri Russell is an advertisement for a “Star Wars” exhibit with a tremendous image of Kylo Ren’s grandfather, Darth Vader. (Driver, at the theater for this interview, always comes in through a different door and so was unaware of Vader’s spectral presence.)

‘White Noise’: Suzan-Lori Parks, Oskar Eustis and how the searing tale came to be »

Driver is humble but engaged while talking about his acting career. He’ll repeatedly return to a question to provide an answer that doesn’t sound generic, and when a publicist gives Driver the high sign about returning to rehearsal, he explains that he arrived five minutes late so he doesn’t want to shortchange the interview.

But what really revs Driver up is talking about the nonprofit he and his wife, Joanne Tucker, created: Arts in the Armed Forces brings the power of live theater to the men and women of the military through readings and monologues featuring the likes of Laura Linney, Susan Sarandon, Corey Hawkins, Jake Gyllenhaal, Frances McDormand and Michael Shannon. The organization has “blossomed into something bigger,” he says, providing playwriting grants to members of the military, doing art installations and presenting films. “It’s incredibly satisfying.”

Driver is consumed with “Burn This,” but this run coincides with the release of his biggest leading role on screen to date in Terry Gilliam’s “The Man Who Killed Don Quixote,” which famously took the director three decades — and numerous false starts — to make. “He was one of those directors I discovered in high school and I remember thinking, ‘What’s his next movie? I can’t wait to see it,’ and back then it was ‘Don Quixote,’ ” Driver says with a laugh. “Suddenly fast forward and there I am on the set of that movie. I’ve had a lot of surreal experiences in my very short career, but that was certainly a big one.”

What was the appeal of doing ‘Burn This’?

Every night, there’s a new theme that I think of. Every time I listen to it now, I notice how much it’s a play about work. And there’s an opera theme — everybody in this play has an aria. Every well-written play is always relevant, with a theme you can latch on to, even if it’s not why you started doing the play: What I initially loved about the play was the theme of loss. This was written in the 1980s and it was Lanford Wilson’s AIDS play — looking at what it is like when someone really beautiful is just gone, immediately, and no one has an answer for this, and there are no words to articulate it. But then you start thinking about the work theme. I’m not trying to be cagey, I just hesitate to say a play is just one thing, that there’s one answer to carry you through the entire run. Does that make sense? I sometimes get lost in my own answers.

Does performing in front of an audience change the show even after all that rehearsal time?

Totally. You’ve been in a cocoon and have done the play so many times you forget what it’s like seeing it for the first time. In a way, the audience tells you about the play. And it’s different night to night.

Also, choices you made early don’t always work on the stage, which is so different from the rehearsal room. The blocking is different, and there’s the set and the lighting. It’s different in a million little ways. There were things you didn’t think were funny which seem to be, and the opposite is true. But sometimes you have to change things because you see it’s not the story you were trying to tell. There was a moment that was getting a laugh, and we weren’t sure if it was the line or if it was the color of the pants one character was wearing. So we changed it and realized, “Oh, it was the pants getting the laugh.”

Sometimes people laugh in strange places, when it’s an emotionally charged moment, for instance. Does that ever throw you off?

Some people may be laughing because it’s uncomfortable. It’s what I enjoy most in the theater, when something happens and people aren’t sure how to read it. Some are reading it one way and others read it differently. The audience is at war with itself a little bit. That’s fun. There are a lot of moments like that in “Burn This,” which is a testament to Lanford’s writing.

So I’ve been watching all your movies doing research for this interview and —

Oh. Sorry. (He laughs.)

You have great range in the characters you play, and a nice spin move while playing basketball in “While We’re Young” —

(Laughs again.) Thank you very much.

Do you consciously go from movies like “What If” to “Star Wars” to “Paterson” to “Silence” to challenge yourself to stretch as an actor, or is it just what appeals to you in that moment?

It’s a bit of both. Film is a director’s medium, and Jim Jarmusch and [“The Last Jedi” director] Rian Johnson are so very different. But that’s what I love about this — a great movie is “Jaws” and it’s “400 Blows” and, I don’t know why I picked those, but I love all different movies, and if the director is really good that’s what makes me interested. There’s no master plan.

I grew up watching some of these directors’ films so you have to make yourself available. I don’t do anything unless it’s a no-brainer — if someone wants me to do a Spielberg movie, well, it’s kind of obvious, I’ll do that.

Does getting cast by so many great, even legendary, directors erase any self-doubt you may have had?

Self-doubt is where I live. I don’t quite know how to process how lucky I’ve been. My goal when I graduated from Juilliard was literally just to make a living as an actor. (He stops and catches himself.) Oh sorry, I’m trying to avoid saying literally. The cast was just talking about that word yesterday. I definitely didn’t expect to look back after 10 years at these people I’ve gotten to work with. It’s insane to me.

Why is Arts in the Armed Forces so important for you?

I came late to the theater and was at Juilliard after the Marines when I discovered all these great playwrights who were so articulate in a way that I wasn’t. Through these plays, I was able to articulate certain things for the first time in my life. Coming from my environment, words weren’t as important — using language to articulate a feeling in the military community is not something that’s encouraged. The entertainment for troops that exists is all dumbed down to the lowest common denominator; considering people are asked to put their lives on the line, I thought they could handle something more thought-provoking. If you look at “Burn This” from a military perspective in front of that audience, it’s a play about loss, someone within a community that’s suddenly gone, which is hard to process. It’s simple — just four people in a room talking about their feelings and problems — but there’s an energy and an urgency. My work with Arts in the Armed Forces actually made me want to go back on stage and do this play.

See all of our latest arts news and reviews at latimes.com/arts.

Pulitzer winner: The conceptual brilliance of Jackie Sibblies Drury »

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.