Four radical and radically original pieces of music that blew up the modernist status quo in 1968

On a cold Berkeley morning early in December 1968, I cut class and joined a queue on Telegraph Avenue, waiting for Discount Records to open. The line wasn’t as long as the one I’d joined for the Beatles’ White Album a week or two before, but it was sizable and included many of the same fans. This time our impatience was for the first recording of Terry Riley’s transformative “In C.”

“In C,” which had premiered in San Francisco four years earlier, would ultimately be credited with formulating the Minimalist movement in music that Steve Reich (who performed in the “In C” premiere), Philip Glass and later John Adams would further pioneer and eventually make mainstream. Minimalism would herald an unexpected inventive return to consonance, traditional harmony and pulse, all of which had little appeal to modern music, academic or avant-garde.

I later carried the LP, which came with the score of the piece (a first) into a class on fugue writing. I hadn’t known at the time that Riley had taken the same class with the same professor, composer William Denny, a dozen years earlier when he was a student at the University of California.

Denny was a refined and mild-mannered musical conservative who could bring himself to teach in the afternoon only after he had a few cocktails with lunch. He required us to write only in ink using fountain pens equipped with music nibs. We studied the same 19th-century French textbook that Debussy railed against at the turn of the 20th century.

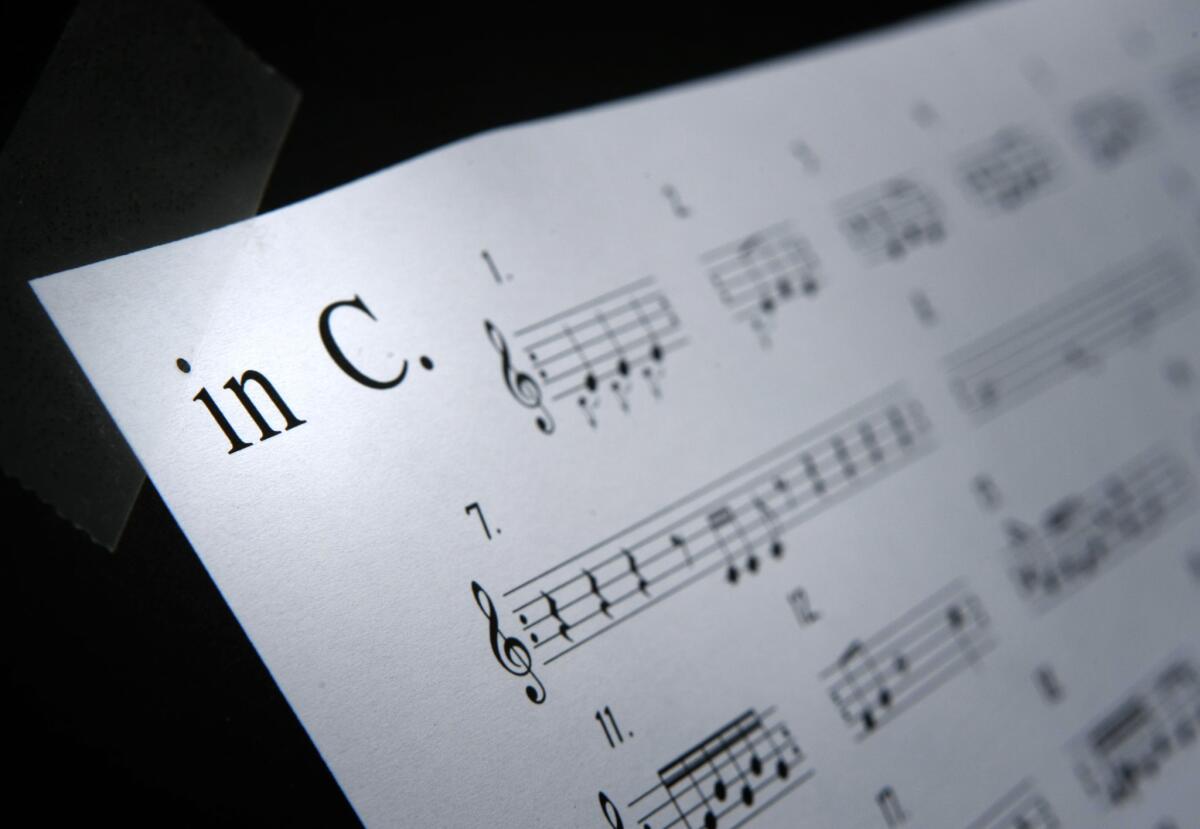

Riley’s “In C” violated all that Denny held holy. It is simply a collection of 53 melodic motives, all in or around the key of C. Any instrument or vocalist — and any number of them — can play or sing. Each motive is repeated, over a pulse, as long as each performer wants before moving on.

When he saw my recording of “In C,” Denny became startlingly apoplectic. Riley, he said, had been a brilliant student, and now look what he had done! Centuries’ worth of contrapuntal development that led to Bach’s sublime fugues and Bartok’s wondrous string quartets was seemingly discarded by the stroke of a musical anarchist. I was told not only that I couldn’t bring that sacrilege into the classroom, but to get it out of the music building and that the only place for it on campus was the trash can.

That’s when I knew the revolution had begun.

Centuries’ worth of contrapuntal development that led to Bach’s fugues and Bartok’s string quartets was discarded by the stroke of a musical anarchist.

It all somehow happened around the same time. And to a significant, if little acknowledged extent, the Bay Area was the stimulus for much of its mind-set.

Along with the release of “In C,” over a two-month period at the end of the momentous year, between Oct. 10 and Dec. 9, 1968, three other radical and radically original works had their premieres. Each was, in some way, a product of political protest and the counterculture that would, along with “In C,” permanently transform how we think about and make music. A half-century on they have become classics, no longer shocking, perhaps, but newly pertinent to a later age of anxiety.

The first was Luciano Berio’s “Sinfonia,” by far the most notable of the New York Philharmonic commissions celebrating its 125th anniversary. In it, the Italian composer managed to mix political and intellectual trends with Mahler (“Sinfonia” is dedicated to Leonard Bernstein), sophisticated avant-garde procedures of 12-tone composition and extended vocal techniques (in a movement memorializing the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., assassinated six months earlier). He furthermore employed the hit crossover group known for jazzing up Bach, the Swingle Singers, in the process.

In all, “Sinfonia” single-handedly revived the symphony, then thought dead, as a viable genre for progressive composers. But it was the Swingles that really caught attention. Rather than trying to popularize symphonic works (such as William Russo’s “Three Pieces for Blues Band and Symphony Orchestra,” which Seiji Ozawa premiered that summer with the Chicago Symphony) or doing a pop version of the kind of collaged electronic pieces Berio was also noted for (say, the Beatles’ “Revolution 9” on the White Album), Berio extended his scat singers into entirely new realms of extended vocal techniques and speech.

He came on that idea a couple of years earlier while teaching a graduate composition seminar at Mills College in Oakland. Next door, the head of the music department, who had hired Berio (and later hired Riley), was trying to enliven an undergraduate class on Bach by loudly playing the Swingles’ hit “Jazz Sebastian Bach.”

As Margaret Lyon told the story, Berio stormed into her classroom, grabbed the disc off the turntable and left the building. She was sure he was furious with her for disturbing his teaching. But he was excited not angry. Hearing the Swingles had been Berio’s a-ha moment for “Sinfonia.”

Two months later, in a Paris still reeling from the May student protest, Karlheinz Stockhausen unveiled “Stimmung.” Nicolas Slonimsky, the Russian conductor and lexicographer who taught at UCLA at the time, described that premiere as “six shoeless singers sitting cross-legged in a circle with musical material selected from a matrix of 50 one-pitch patterns and occasionally intoning ‘magic names.’” This became the kind of late ’60s musical mystical tuning in (literally in this case), turning on and dropping out that inspired a generation of composers.

Minimalism would herald an unexpected inventive return to consonance, traditional harmony and pulse, all of which had little appeal to modern music.

It was also a response by Germany’s most visionary composer to Berio and Riley. Stockhausen happened to be teaching at UC Davis and living in Sausalito around the time that Berio was at Mills and Riley was beginning his Minimalist experiments. The turning on was supplied to Stockhausen by the Eastern mysticism, psychedelic reverie and free love that pervaded the Bay Area hippie culture.

On the same December day that “Stimmung” was first heard in Paris, Hans Werner Henze attempted to conduct the first performance of his “The Raft of the Medusa” in Hamburg, Germany. The politically pointed oratorio was dedicated to Ché Guevara, and a group of students ran a Communist red flag up on the stage. The chorus refused to sing, the police were called and the librettist was arrested in the melee. The left-wing composer canceled the premiere in response, proclaiming world revolution more important than new music.

Henze and his forces, which included famed baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, did, though, go into the recording studio. A two-LP set was released the following year and became a model for how to make an uncompromisingly powerful political statement using the full resources of conventional forces and contemporary techniques.

Fifty years later, “Raft of the Medusa” retains surprising power and feels especially daring, a precursor of such works as Julia Wolfe’s oratorio, “Anthracite Fields.” Henze’s oratorio also retains a freshness, since has been basically neglected until recently (in Hamburg it has been revived to mark its 50th anniversary).

On the other hand, the 1968 Bay Area-derived pieces by Riley, Berio and Stockhausen are ever with us (the Los Angeles Master Chorale performs “In C” in May). Their lasting impression is not so much of a new accessibility now taken for granted as inspiring an open-mindedness. Thanks in great part to them, 1968 can be seen as having broken down not only political barricades but musical ones as well. It’s fine to try new things, or not.

A surprising example of that can be found in the boxed CD set of riveting remastered recordings the Juilliard Quartet made on the Epic label between 1956 and 1966. That includes William Denny’s String Quartet No. 2, which came out at the time Riley was in his fugue class.

I vaguely knew that it existed, having seen the old LP a time or two in used record bins, but never paid it any mind. It is a beautiful, melancholic quartet. The counterpoint is elegantly crafted. But the style was anachronistic for its time. The quartet had no legs.

Hearing it now, juxtaposed with “In C,” I understand, as I couldn’t have possibly then, just how threatening 1968 was to the old order, and it brings a tear to my eye. The great irony is that the 1968 generation’s legacy is to have ultimately broken down dogmatic stylistic barriers that had once prevented us from responding, as we can now, to Denny and Riley alike.

Even more remarkable, I now hear echoes in Riley’s own string quartets of the contrapuntal respect we all got from Denny. He deserved better. Revolutions can be like that — necessary yet sad.

More on the cultural shifts of 1968

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.