Firecrackers, a striptease scandal and more moments of change from the Hammer’s ‘Radical Women’

The idea that artistic geniuses were generally men was a hard one to shake in the 1970s, especially in Mexico. Enter a generation of Mexican women who helped bust those preconceptions wide open with work that pushed the boundaries of both materials and subject matter.

Those women — along with women from across Latin America — are the focus of the exhibition “Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-85,” which opens at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles on Sept. 15.

Early this spring, The Times gathered a group of the show’s Mexican artists at the home and studio of artist Mónica Mayer in Mexico City for a wide-ranging discussion. The lineup included Mayer, a key Mexican feminist artist, as well as printmaker Carla Rippey, and photographers Lourdes Grobet and Ana Victoria Jiménez. Joining the discussion were historians Karen Cordero and Julia Antivilo Peña, who have contributed essays to the exhibition catalog.

Separately, I interviewed artists Maris Bustamante (who, with Mayer, established the iconic feminist collective Polvo de Gallina Negra) and Magali Lara, an artist known for her intimate assemblages exploring aspects of female sexuality.

In this edited oral history, they discuss what the Mexican art scene was like when they first emerged, the controversial nature of identifying as feminist, and the ways in which their works helped evolve the art of the time. Plus, there’s that one fiery anecdote about a dozen bored university students and a handful of firecrackers.

A political tradition

Mónica Mayer: I think you have to understand that Mexican art has a long tradition of political art — a very long tradition. [In the 1970s] art was collective and it was political — at a time when practices such as performance, installation, ephemeral art, all of those things — became more prominent.

Mexico, not Europe, first

Magali Lara: In school, it was all about technique, about formal qualities, about the connection to Western ideas about the universal. But it was my generation that said, “We live here. Why talk about Mexico if everything we have to do focuses on European thinking?” It was a period in Mexico in which anthropological studies were very strong, and there was this whole recuperation of indigenous culture — not as something of the past, but of the present.

The male mindset

Carla Rippey: Among los grupos [the collectives that became popular in Mexican art in the ’70s], I think they did function as collectives. But the men were generally thought of as the leaders. I was in the grupo Peyote y la Compañia, and it was always seen as being led by Adolfo Patiño — even though I organized as many things as he did. But people saw him as the leader and the rest of us as the group. It was very typical.

Yes, women paint

Magali Lara: I was at the Academy of San Carlos [now part of the National Autonomous University, known as UNAM]. We used to have these discussions which today would be considered absolutely ridiculous, but back then were very serious. We’d talk about whether women could or couldn’t be painters because of our maternal qualities, and how women were good students but not good creators. This idea that we were very docile and easily influenced — that’s how they treated us.

Breaking the feminist stigma

Maris Bustamante: I remember Mónica and I decided to establish a feminist art group. So we organized a meeting. We invited like 50 or 60 women: curators, writers, sculptors, illustrators — everyone! We had coffee and cookies. And everyone told us they didn’t want to be in the group.

They gave several reasons. One was, “I don’t have a problem being a woman artist.” Some said, “I don’t want to have any problems exhibiting because as it is, it’s hard enough.” The galleries were run principally by men. The word “feminist,” it created this conflict.

RELATED: How Mexico's súper rudas 'Radical Women' are rewriting the history of Latin American art »

The ‘libber’ label

Carla Rippey: In the 1970s, nobody liked to say “feminist” — even in the United States. They would say “women’s libbers,” which sounds terrible. Not even “women’s liberation.” It was “women’s libbers.”

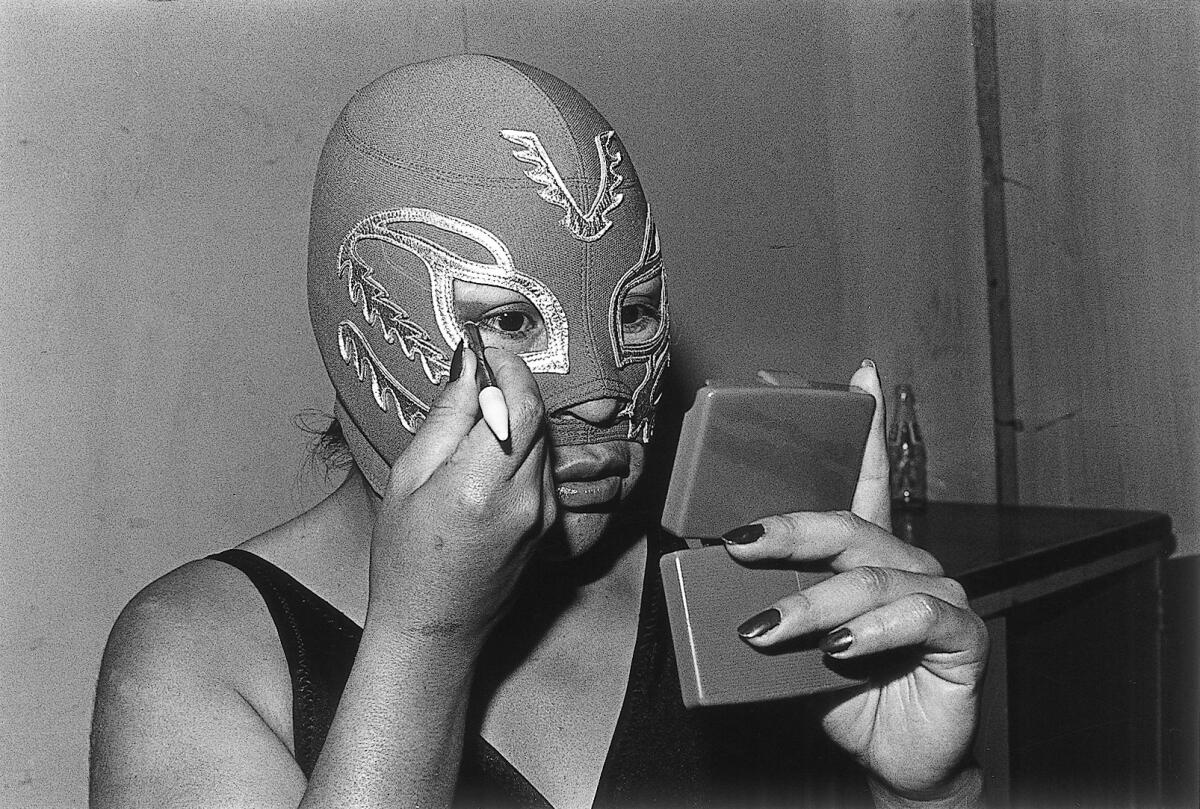

Lucha liberation

Lourdes Grobet: I always questioned the whole concept of feminism because I always felt as if it was imported from Europe or the United States. It’s a word that struck me as very middle class. And this issue of the influence of European culture, I’ve always been wary of that. Mexican women are different, and especially Mexican rural women. So it’s another context. That’s why I’ve been dedicated to things like lucha libre [Mexican wrestling] instead of keeping my eye on what’s happening in Paris. All of my colleagues were always in Paris.

White and bourgeois?

Mónica Mayer: Since the ’70s people have repeated the idea that “feminism is white and bourgeois” — even feminists themselves. And that overlooks a whole other struggle, which is the struggle between women and the left.

Legitimacy

Julia Antivilo Peña: That’s what the left used to say, that it was bourgeois, in order to delegitimize the movement. … But in the ’70s, and even before then, there was a feminist movement here.

Feminist congress

Karen Cordero: Mexico has had a feminist movement since the 19th century — and a very visible one. The first feminist congress in Mexico took place in 1916, in Yucatán, and since then, there has been visibility for feminism in Mexico.

Making babies

Ana Victoria Jiménez: It’s very complicated. We’ve always gotten into this discussion. Whether it was good feminism because it came from England in the 1800s or bad feminism because it came out of U.S. imperialism in the 1900s. And that has separated us a lot.

There were things about the leftist movements of the 1970s that I was not in agreement with. They were not in favor of abortion, because they wanted children for the revolution: the concept of “a parir madres Latinas” [a 20th century leftist hymn that encouraged women to give birth to future revolutionaries].

“A parir madres,” frankly, used to make my hair stand on end. You are fighting for independence, for the liberation of women, for a dignified life — and someone comes along to tell us that if we’re not good at making babies, then you don’t count. Those concepts from the ’70s, to me, were really problematic.

Diego 50, Frida 20

Magali Lara: In ’76 or ’77, I showed these drawings that showed objects like scissors and cameras having these somewhat sexual interactions with bits of text. And it was chaos because it was made by a woman. They also weren’t paintings, they were drawings. In the gallery, they would erase my name and write “whore” and “dirty” in place of the wall text. It was a huge surprise.

My generation was a big fan of Frida Kahlo because she was using herself as a subject, commenting on the subjectivity of the body. She used paint in a European way but painted indigenous forms. She had this aspect that was very high culture but also very populist. It was a real mix of things. This was when nobody went to Frida’s museum. We were the only ones who went. And there was one book about Frida Kahlo, which was 20 pages about Frida and 50 about Diego [Rivera].

!["Ventanas" [Windows], 1977-78, by Magali Lara. (Acervo Museo de Arte Moderno. / INBA-Secretaria de Cultura, Mexico City)](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/e21e2b6/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1884x2048+0+0/resize/1200x1304!/quality/75/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcalifornia-times-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2F1f%2F06%2F9287db3b444621efa581857b9d86%2Fla-1503947548-runwsgmwv8-snap-image)

The taco patent

Mónica Mayer: From ’75 on we were making works of feminist art. And in 1977, the exhibition “Collage Íntimo” [Intimate Collage] was held, which was the first self-described show of feminist art.

In ’83, Maris and I formed the collective Polvo de Gallina Negra, and our idea was that we would make a public art, and that it should be public in the most massive way possible. We had an opportunity to present on television because Guillermo Ochoa [who hosted a television talk show] approached Maris after hearing that she had patented the taco. She had done a conceptual piece where she patented the taco — she was listed as its intellectual author. It caught his eye, and so we did a performance.

Firecracker discipline

Maris Bustamante: The lectures that Mónica and I gave, we talked about the work of women artists and recuperating the work of women artists who had died. And we always appeared wearing an apron — because people always said, “Women in the kitchen.” So we would come from the proverbial kitchen to the stage.

There was one event, when the students found out what the theme of the talk was, like 12 of them got up to leave. I was always prepared. In my apron, I carried all kinds of things: pingpong balls and water pistols. I had these little firecrackers. You throw them, and they make a “pop.” So these 12 or 15 young people stand up, and I grab the firecrackers, and I throw them on the table, and they explode perfectly. And I say, “From a lecture on feminist art, nobody leaves!” It was a joke. But the students sat back down. We laughed so hard.

A striptease scandal

Lourdes Grobet: I remember a piece that I did on a tour with other women artists. I organized a striptease. I do a striptease, but I don’t take off my clothes. I had photographed myself doing a striptease, and I go removing the photos, and I end up nude in the photos. You don’t even know how much that irritated people. In San Cristobal, it was a scandal.

Afterwards, I was invited to a colloquium on photography in Pachuca, and I presented the striptease. My photographer colleagues were horrified. Someone asked me, “Do you have children?” And I said, “Yes! Four.” [Laughs.] They were horrified that I had shown myself nude like that.

Turning the tables on soft-core

Carla Rippey: I worked a lot with the female nude. I would take images of Victorian soft-core porn but try to re-imagine them from the point of view of the woman — of the pleasure they felt. I made other types of works, too. Some of the feminists had problems with my work. They would say things like, “What are you trying to do?” “Is this feminism or not?”

Internalizing art

Karen Cordero: Feminism in Mexico hasn’t gotten very close to art. At the feminist study program at the Colegio de México at UNAM, the thing that has least been internalized is art.

Mythbusters

Magali Lara: I think what “Radical Women” is doing is very important. It will eliminate a lot of myths about contemporary Latin American art. In the European view of art, the Latin Americans who were there, who were part of some of these very important movements, are often missing. Well, in the Latin American view of art, the women who were also there — from the beginning — are also missing. It’s important to show it.

The post-35 drop-off

Carla Rippey: There has been change. The current minister of culture is a woman. The head of the Palace of Fine Arts is a woman. But you still see some of the same problems. The women’s portfolios are excellent — as good or better than the men. But once everyone reaches 35 years of age, when careers are taking shape and artists are being considered for fellowships and grants, the women fall off. That’s something that we still need to understand.

“Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985”

Where: Hammer Museum, 10899 Wilshire Blvd., Westwood, Los Angeles

When: Sept. 15 to Dec. 31

Info: hammer.ucla.edu

ALSO

How Mexico's súper rudas 'Radical Women' are rewriting the history of Latin American art

Hammer Museum's 'Radical Women' to showcase Latina artists on the politics of the female body

Mexico City's art scene is booming, but even with deep roots, political uncertainty keeps it fragile

Argentine slums and a Unabomber cabin: How 'Home' at LACMA rethinks ideas about Latin American art

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.