Tonys 2015: Meet the biggest hit maker on Broadway

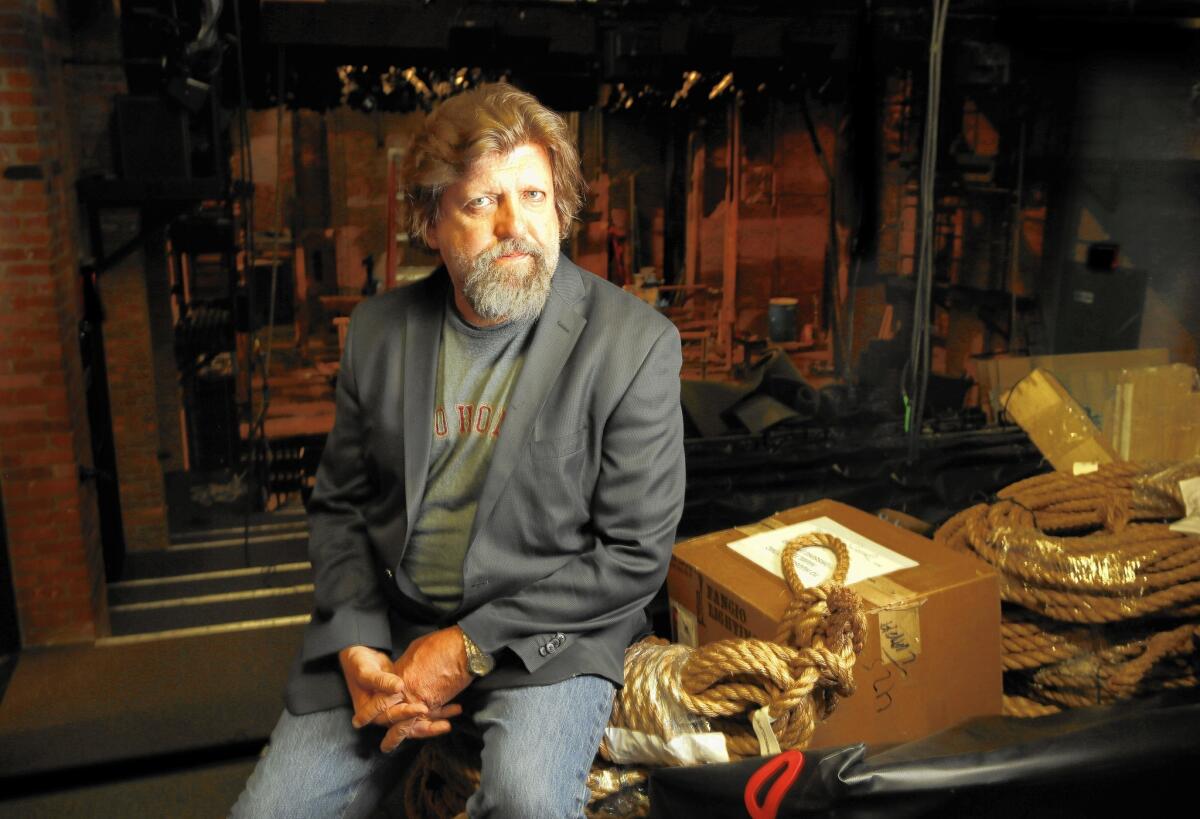

Reporting from New York — Who’s the toast of Broadway at the moment? While fans of Kristin Chenoweth and Kelli O’Hara duke it out, let’s raise a glass to Oskar Eustis, the Public Theater’s game-changing artistic director who, since he began his tenure 10 years ago, has been retooling the American musical at the historic off-Broadway venue founded by Joseph Papp.

Two of the most-talked-about productions of the year — “Fun Home,” which received 12 Tony nominations, and “Hamilton,” the show that will likely sweep the Tonys next year after it opens on Broadway this summer — began at the Public. To call these musicals improbable hits is an almost ludicrous understatement.

“Fun Home,” written by playwright Lisa Kron and composer Jeanine Tesori, is based on Alison Bechdel’s graphic memoir about coming of age as a lesbian in a home with a closeted gay funeral director father, whose death appears to have been a suicide. Even Stephen Sondheim might have balked at the scenario.

“Hamilton,” a rap musical about the Founding Fathers, portrayed by a multicultural cast, is even more unlikely. Written and composed by Lin-Manuel Miranda, the show tells the story of Alexander Hamilton (played by Miranda), the feisty, brilliant Caribbean-born scrapper who shaped what kind of country America would be before his infamous fatal duel with Aaron Burr. What musical theater buff paging through Ron Chernow’s biography of Hamilton would have come to the end of the book and exclaimed, “This has got to be a hip-hop musical!”

Racing into his office from a staff meeting last month, Eustis should be on top of the world, but his heart is heavy. In November, he and his family suffered the loss of his 16-year-old son, Jack. When I asked Eustis how he’s bearing up, he said he and his family are doing as well as can be expected under the worst of all possible circumstances.

Surrounded by photos and images of the Public’s illustrious history — Papp urging him on from the shelf, Hamlet hovering sagely on the wall — Eustis is grateful for the distraction of work and grew animated when talking about this remarkably fruitful season.

An ardent intellectual and old-school lefty, he has been unwavering in his determination to broaden the audience of the Public’s multiplex operation by reflecting on stage the demographic richness of the city. His reward — and the American theater’s — has been a series of critical and commercial successes that have defied the scaremongers and naysayers whose mission is to preserve the conservative status quo.

“Fun Home” and “Hamilton” weren’t happy accidents. They are the product of a carefully worked out institutional vision that Eustis said began with Joe’s Pub, the Public’s adventurous nightclub, and “Passing Strange,” the musical by Stew and Heidi Rodewald of the band Stew & the Negro Problem.

“We were actively searching for ways of taking the musicians at Joe’s Pub and relating them to the drama that was happening on stage,” Eustis said. “The first serious attempt to do that was with Stew. I thought I was doing some kind of wildly experimental musical theater piece, but ‘Passing Strange’ wound up winning the Tony for best book. I was very surprised by the reach of it.”

Eustis, who commissioned Tony Kushner’s “Angels in America” when he was at San Francisco’s Eureka Theatre Company and directed its two-part world premiere at the Mark Taper Forum (where he spent five years as an associate artistic director under Gordon Davidson), wasn’t really known as a musicals guy. His love affair, he said, began at Rhode Island’s Trinity Repertory Company. It was there, as artistic director just before his appointment at the Public, that he started “rethinking classical musicals, trying to tear them apart and make them speak to our moment.”

The “fantastic populist” appeal of these shows excited Eustis, who naturally gravitates toward weighty political dramas, such as Kushner’s “The Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide to Capitalism & Socialism With a Key to the Scriptures,” which the Public produced in 2011. “Kushner is my best friend, and that is my Platonic ideal of a play title, just as the idea of a communist and his family arguing for 31/2 hours about whether it’s worth living in the era after communism has failed is my idea of the perfect play,” he said. “But fortunately, that’s not all we do.”

The Public’s sensational 40th-anniversary revival of “Hair,” a production directed by Diane Paulus that began in Central Park and won the Tony for musical revival, opened Eustis’ eyes further to the expansive potential of shows that express their political conscience through song. He also saw how remunerative they can be.

“I don’t consider that selling out,” he said. “Musicals are the only form that actually holds up the possibility of artists making a living in the theater. It is directly related to the fact that you can reach many more people with a musical than you can with a play. That has felt very mission-centric to us.”

Two years after “Passing Strange” made it to Broadway in 2008, “Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson,” the Alex Timbers-Michael Friedman musical that ran at the Public Theater (after its premiere at the Kirk Douglas Theatre), had its turn. These shows weren’t box-office juggernauts, but they cleared the way for new possibilities.

Of course Broadway isn’t the only measure. “Here Lies Love,” the David Byrne-Fatboy Slim musical about Imelda Marcos staged by Timbers as a floating disco extravaganza, was so successful that it had a repeat engagement at the Public.

Musical triumphs are nothing new at the Public. George C. Wolfe, Eustis’ predecessor, unleashed the meteoric “Bring in ‘da Noise, Bring in ‘da Funk,” while Papp’s business plan hinged for years on “A Chorus Line,” the Broadway blockbuster that started as a downtown experiment and wound up serving as the Public’s ATM.

“Fun Home” and “Hamilton,” however, represent something of an aesthetic breakthrough, extending the work of “Caroline, or Change,” the Kushner-Tesori musical directed by Wolfe, of closing the distance between dramas and musicals.

When asked if “Hamilton” (rapturously endorsed by First Lady Michelle Obama after her visit to the show) might be the Public’s new cash cow, Eustis replied, “No one will ever make as much money from a Broadway transfer again as the Public made from ‘A Chorus Line.’ Because of the peculiar nature of Broadway, which was dying at that moment, we were able to make a deal with the Shuberts that nobody will ever be able to make again.”

He acknowledged this might not be such a bad thing: “It’s a lousy business model to depend on one great commercial hit to fund your entire operation. The Public will receive income from both ‘Fun Home’ and ‘Hamilton’ that will help us, but there’s never going to be a disproportionate amount of money. What we had in Joe’s last 15 years is this very strange reality of the most noncommercial theater in America completely living off of commercial income. That produced in the decade following a lot of upheaval we are trying to avoid.” (The theater’s solid footing is one reason Eustis and his wife, Laurie, a former producer at the Taper, are being honored at a Public gala on Tuesday.)

As economic inequality has grown in this country, so too has the cultural gap between hits and the vast majority of other shows — the 99%, if you will. Could a runaway success like “Hamilton,” the dream of so many nonprofit theaters, establish a dangerous precedent? Eustis, who admitted it hasn’t been easy to work out a tactical yet principled stand toward the commercial world, didn’t need much coaxing to elucidate the pitfalls.

“The hit mentality is the expression in show business of the increasing hegemony of capitalism,” he said. “There’s a tendency to focus on the single show and consign everything else to the trash heap. ‘Fun Home’ and ‘Hamilton’ are probably the two most successful musicals we’ve had since ‘A Chorus Line’ and ‘Bring in ‘da Noise,’ but they are the product of a bunch of other things — a whole history — we’ve been developing here.”

The solution to theater’s commodification, Eustis said, is to “transform it back into a set of relationships.” Public Works, the program led by Lear deBessonet that partners with organizations such as the Children’s Aid Society and Domestic Workers United does just that by inviting members of marginalized communities to share the stage with theater professionals. “The Tempest” and “The Winter’s Tale” were the first offerings, and this summer there will be a musical adaptation of “The Odyssey.”

Eustis said he knew that the program would be exhilarating for participants, but he wasn’t sure about the quality of the productions. “But it has turned out to produce fantastic art,” he said. “I don’t like to compare children, but the productions were as thrilling to me as ‘Hamilton’ and ‘Fun Home.’ For ‘The Tempest,’ we had little kids next to senior citizens from Brownsville next to Laura Benanti next to guys who recently got out of prison after 20 years — all performing Shakespeare together. This is the mix that makes this place vital.”

A utopian in the Papp-ian mold, Eustis is trying to figure out how to expand the box office policy for Shakespeare in the Park. He’d like the majority of tickets for shows at the Public, which operates five theaters and Joe’s Pub downtown as well as Central Park’s Delacorte Theater, to be free while making a percentage of seats available at premium donation prices.

Deeply concerned about the “crisis of artistic compensation,” he’d like to be able to do for other artists what the Public has done for Suzan-Lori Parks, who wrote “Father Comes Home From the Wars (Parts 1, 2 & 3),” a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize this year, while in residence. “That play came about because she had a salary and a secure base at the theater over an extended number of years,” Eustis said.

As for the criticism that the Public has been more loyal to the old guard than open to the new, Eustis pointed to the Emerging Writers Group, the two-year fellowship program that was an important steppingstone for the now red-hot Branden Jacobs-Jenkins (whose play “Appropriate” will be produced at the Taper in the fall). But he acknowledged that there was more to be done: “There aren’t as many Tarell Alvin McCraneys as I wish there were, younger artists who we’ve made a really long-term commitment to.”

With “Hamilton” and “Fun Home” galvanizing new audiences — not even a cellphone-fondling Madonna could resist the siren call of “Hamilton” — it’s hard to complain. Is there a cost to such far-reaching appeal? Do the politics have to be diluted for the masses to flock?

“Peggy Noonan, Lynne and Dick Cheney and Barbara Bush all loved ‘Hamilton,’” Eustis said. “These are not my normal political bedfellows, and I had a crisis of conscience. But my wise friend Tony Kushner pointed out to me that the success of ‘Hamilton’ is precisely embodied in the fact that it is convincing everybody of the fundamental accuracy of the need to see this nation as a nation of immigrants — the need to see people of color as central to owning the nation. I think the show is actually going to move the needle on how we think about immigration precisely because it’s reaching people.”

“Fun Home,” Eustis believes, has the potential to do for lesbians what “Angels in America” did for gay men: “Take a marginalized group and say, ‘No, you are actually center stage.’”

“The art form, contra Brecht, depends on empathy,” Eustis said. “It has been magical watching Broadway audiences at ‘Fun Home.’ No one is thinking, ‘Oh, I know a lesbian.’ They are identifying themselves with the story, and that changes you. Once you’ve identified with someone, you can’t think of them as the other anymore.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.