Critic’s Notebook: Mozart in Trump Tower, and the art of getting political onstage

Opera knows a little something about conflating Julius Caesar with an American president. It also knows a little something about Donald Trump.

In the early 1980s, a young director made a name for himself by staging a daring production of Handel’s “Giulio Cesare.” It opened with a news conference at a fancy international hotel by a cocksure U.S. president having just arrived in the oil-rich Middle East.

“The text of his speech,” as Peter Sellars wrote with strange prescience in his updated plot synopsis of an 18th century libretto, “concerns itself at length with the palm trees, which he clearly admires. Perhaps they remind him of Palm Beach. Let them belong to the victors.”

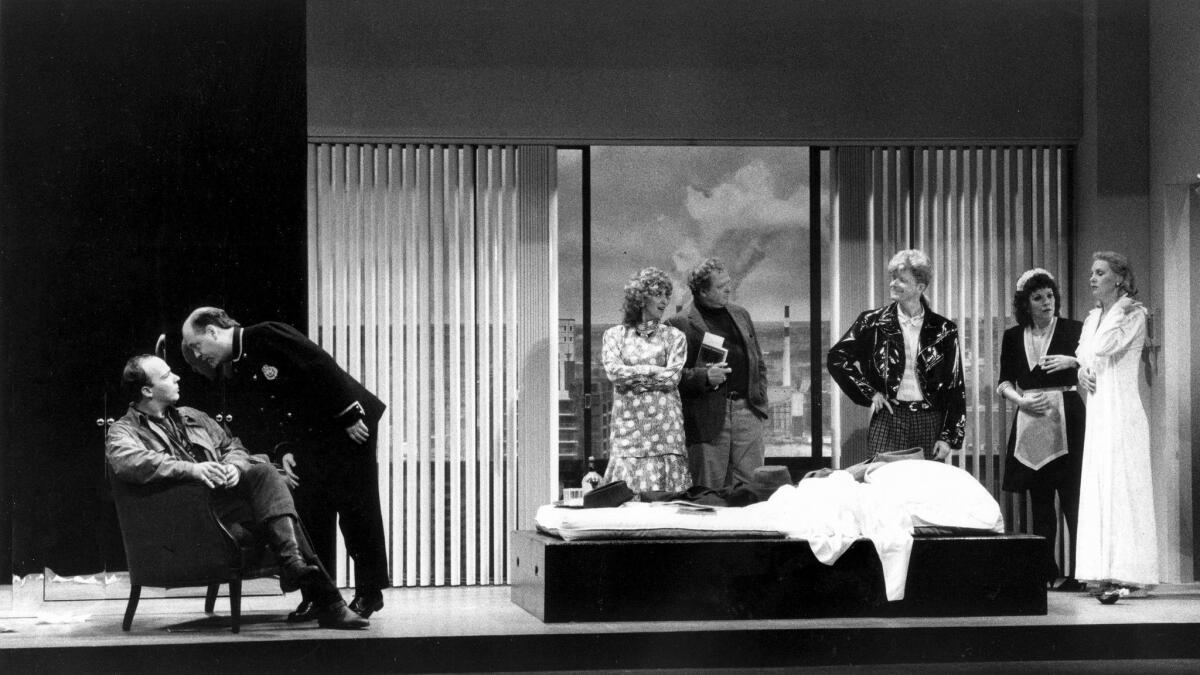

A few years later, Sellars famously set Mozart’s “The Marriage of Figaro” in an apartment in the then-new Trump Tower, 52 floors above Fifth Avenue. This is the world, to quote Sellars’ plot synopsis of an old libretto again, of beautiful people for whom “perjury, loss of happiness and absence of consciousness can be compensated for by the feel of money, the sense of being on top and the sweet certainty that their own barren lives will be enriched by the amusement and consolation offered by the collapse of the hopes and plans of others.”

Neither of these examples, however, was a foretaste of the Public Theater’s recent production of Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar,” which portrayed Trump as the Roman emperor. Sellars did not presume direct correlation between past and present. The U.S. president was someone in the future, not specifically Ronald Reagan, then in office. The “Figaro” apartment in the Trump Tower was not Trump’s gilded one but a modern duplex dominated by a large Frank Stella-like painting. The Count in no way physically resembled Trump or his lifestyle.

In both cases, Sellars wasn’t in the business of singling out individuals. Handel and Mozart were artists with great insight into society, and Sellars was instead seeking what light their work — work that has survived centuries — shined on our own values.

That might sound very much like the intent of the controversial New York Shakespeare in the Park production of “Julius Caesar,” with a Caesar resembling Trump. Director Oskar Eustis sounded as though he was after something similar to what Sellars was up to with Handel and Mozart, using Shakespeare’s tragedy as a mirror to nature, often revealing “disturbing, upsetting, provoking things.”

The result then offers, you might say, a teaching moment about the ramifications of political violence. As a general, Caesar had committed genocide, killing nearly every soldier-age male in Gaul, possibly as many as a million. He was assassinated by a cabal of senators when, after declaring himself a god, he attempted to turn the republic of Rome into a kingdom. Follow this parallel with Trump through to its logical conclusion, and you would need to have Caesar’s last words in the updated play be “Et tu, Bernie.”

From there, anything ridiculous goes.

Opera is far from blameless in unscrupulous updating. But when the intent is noble, the point is not to place a specific individual in someone else’s shoes. When Sellars has chosen to focus on historical figures, such as Richard Nixon or Robert Oppenheimer, he made a new opera about them as a way of better understanding their inner lives. When he updates a classic work, he helps us to imagine ourselves capable of the spiritual growth that Handel proffers his Caesar and Mozart his Count.

In the end, a director has to be true to the work, or everything starts to unravel. Instead of generating a discussion about political violence, the recent “Julius Caesar” seemed to incite dangerous vitriol. Public Theater sponsors Delta Air Lines and Bank of America pulled their support.

So now we have a new debate about whether we should patronize companies that don’t stand for what we believe to be right. Therein lies another cautionary tale.

Around the time Sellars made his “Giulio Cesare” and “Figaro” productions, the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s most generous sponsor was Philip Morris. That led a few artists to boycott BAM for accepting money from a tobacco company.

The difference here was that the chairman of Philip Morris happened to be an arts lover. When asked by the New York Times whether the BAM sponsorship was intended to improve the company’s image, Hamish Maxwell’s reply was that he was thinking of it more as a stimulus to his employees. Philip Morris employees got discount tickets, and the exposure to avant-garde art was a way to inspire them to be more innovative. And this was in the Reagan era, no less.

The Public Theater has admirably stood up to Delta and Bank of America, saying that it will not be censored by any sponsor. Both companies will find they can’t win, since pulling out of the Public will prompt other customers to boycott them, which has the unfortunate consequence of changing the subject once again. Is it OK to fly an airline or bank with an institution only if it gives money for Shakespeare in the Park?

How much harder will it be to get other companies to support the arts? Will arts groups less financially robust as the Public rethink the kind of work they put on, lest they create a controversy and lose sponsorship?

It’s not a pretty picture. It is also one that opera, generally the most expensive of the performance arts, faces regularly. Censorship is part of opera history, and composers and librettists have found all kinds of innovative ways around it. Handel did so by being entrepreneurial. Mozart, by being subversive.

Companies today in countries like Germany and Austria get massive state support with few or no strings attached. Elsewhere though, young people are thinking about opera on a much smaller, independent scale that allows more freedom, especially when they see what happens when an opera is misunderstood.

The Metropolitan Opera pulled the radio broadcast of John Adams’ “The Death of Klinghoffer” three years ago because of pressure from a sponsor. However unsympathetic the opera ultimately was to terrorism, it prompted death threats and protests from people who objected to showing the underlying thinking and emotions of both sides of the Israeli and Arab conflict. This sours the American opera scene, which increasingly plays it safe.

There are no simple answers. Things may well get worse before they get better.

Artists can’t pull punches. But the punches need to hit the mark. Treating theater as an early warning system, like the recent “Julius Caesar,” does little good when it preaches to the converted and offends those for whom the warnings are meant. Giving offense, moreover, has become honey to social media.

But showing the capacity for grace in the graceless, as Sellars did with “Giulio Cesare” and “Figaro” and as he promises to do this summer in his Salzburg Festival production of Mozart’s “La Clemenza di Tito,” in which an emperor learns compassion — that is where hope lies. That is theater’s one chance of being lucky enough to change minds.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.