Review: ‘This Brush for Hire: Norm Laich and Many Other Artists’ at ICA LA

Norm Laich has produced more astonishingly diverse, profoundly significant art during the last 30 years than just about any other American artist.

The catch: He’s made just about all of it for other artists. At least two of those works, one by John Baldessari and the other by Mike Kelley, are incomparable masterpieces.

In addition to his own Pop-related art, Laich has helped to fabricate work for more than 100 artists, most (but not all) based in Los Angeles. A good, representative chunk of that work is currently on view downtown at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. “This Brush for Hire: Norm Laich and Many Other Artists” features 19 paintings, sculptures and installations, plus documentation for an additional five, by 19 artists.

The guest curators for the show are Baldessari and Meg Cranston. Laich has worked with both over the years. One artist considering another’s way of thinking about and contributing to shared production is a pretty good description of what Laich has done since he moved west from Detroit in 1985.

Since then, Laich has been what Jack Brogan was for a cohort of Light and Space artists starting in the 1960s. Brogan solved technical problems in difficult sculptures and perceptual installations for artists such as Robert Irwin and Larry Bell. Making a flawless nine-foot prism of clear acrylic or the calibrated lamination for a glass cube wasn’t easy. (In 2012, the now-defunct Katherine Cone Gallery did an ICA LA-style show of Brogan’s contributions, titled “You Don’t Know Jack.”) For a subsequent generation emerging in the wake of Conceptual art, Laich has specialized in art that incorporates language.

The show errs badly in not specifying Laich’s primary contribution to each work, which is what we want to know. A former sign painter, he can nonetheless be assumed to have worked on any text, whether painted, stenciled or manufactured as a decal, unique or removable.

Sometimes, the language borders on incidental. Cranston’s “Fireplace 18” affixes a decal-like painting of a human-size Bic cigarette lighter to the wall. It’s one of a series of acrylic paintings on paper in which she chose the lighters’ colors not from nature but from the Pantone Corp., the widely used commercial system of hues created for clients in advertising, fashion and industry.

Color in art is traditionally described in spiritual and emotional terms. For a disposable Bic lighter, titled as a communal hearth, those personalized attributes give way to the generalized consumer dictates of planned obsolescence.

Elsewhere in the show, words are everything. In Amanda Ross-Ho’s vinyl wall drawing, the phrase “a very very very rough proposal” appears to have been scrawled in black marker on the white gallery wall — all caps, no punctuation. It is followed by the kind of quick scribble one makes on scrap paper to see whether any ink is left in the pen.

Art is just a beginning, this eccentric but savvy mural says — whether the work is abstract like the scribble or figurative like the words. Viewers pick up the production of meaning from there, embellishing and interpreting what they see.

Brogan began as a cabinetmaker, a material discipline that rises or falls on producing acute physical refinement. Laich started as a sign and billboard painter. A Laich hamburger menu sign painting is in the show, and he’s reportedly a fan of the late billboard painter-turned-artist James Rosenquist.

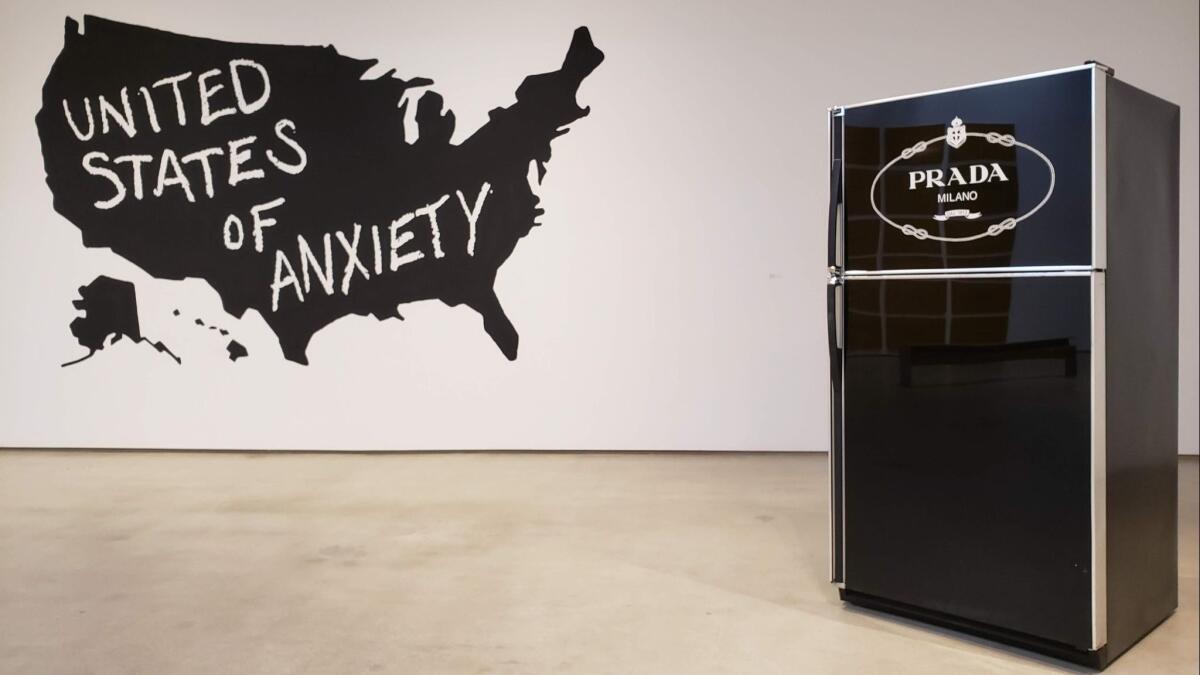

In Scott Greiger’s 1996 “United States of Anxiety,” chalky white lettering on a blackboard-like map of America appears agitated. Current events — the Unabomber’s arrest, the U.N.’s nuclear test-ban treaty, Osama bin Laden’s declaration of jihad against a U.S. military base in Saudi Arabia — may or may not have been an impetus. But the mural is a pedagogical lightning flash in the dark, a lesson plan on the human condition.

John Boskovich shrink-wrapped a clunky refrigerator in an elegant but frivolous Prada fashion label. By keeping perishables fresh a bit longer, the black appliance is charged with staving off the inevitability of death. Its stylish look is suitably chilly — vanity clothed in a little black dress.

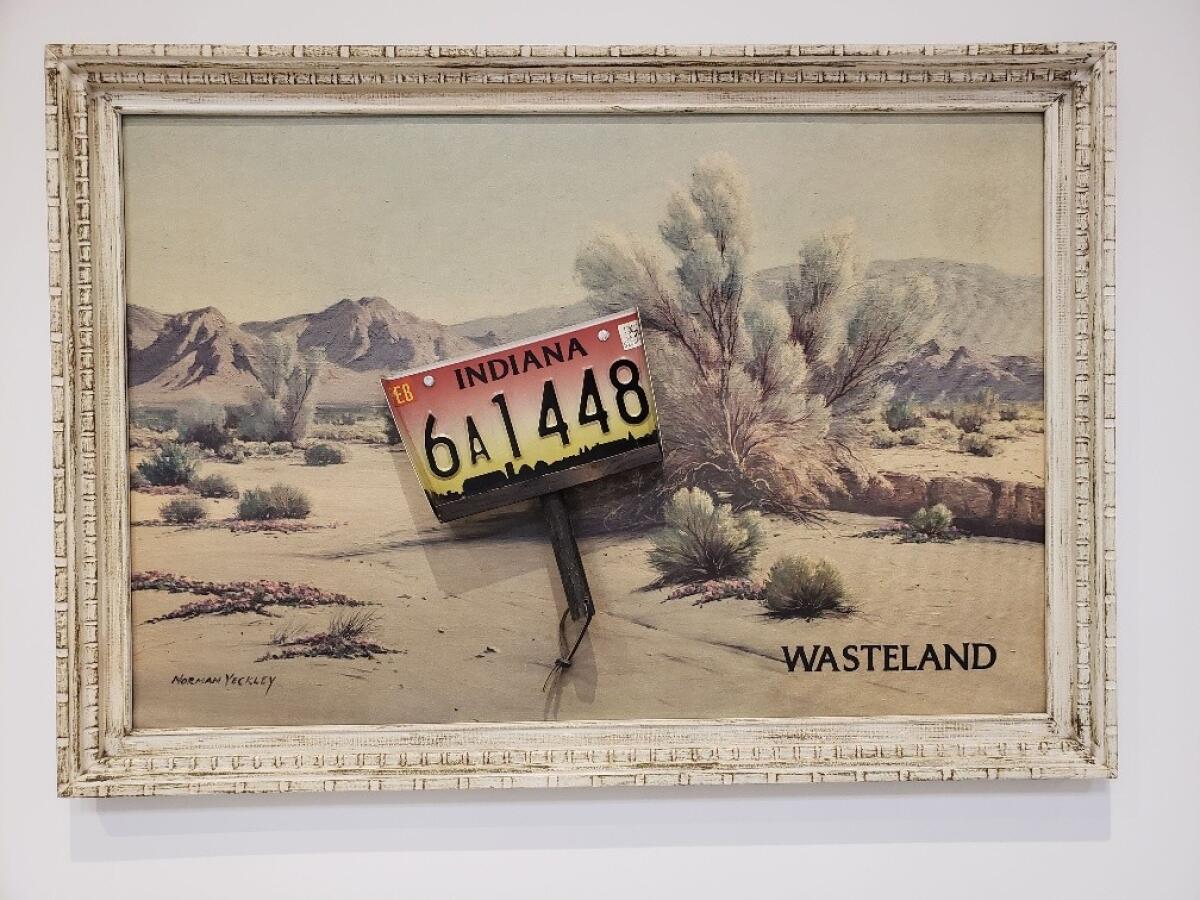

An assemblage by Alexis Smith shows the searingly hot Sonoran Desert in a found-reproduction of a tourist painting, coolly captioned with the Laich-painted word “Wasteland.” T.S. Eliot’s classic poem meets a desolate wilderness.

The barren wasteland gets underscored by an automobile license plate Smith bent, folded, attached to a dustpan handle and stuck in the middle of the picture. It’s an “Amber Waves of Grain” auto tag, issued a quarter-century ago by the state of Indiana. Sunset colors rising behind a darkly silhouetted Midwest farm assume a mordant glow in the Western desert.

Meanwhile, as always with Smith, the twilight astringency of her meditation on mortality melds with sardonic wit. The tourist painting’s signature names Norman Yeckley, a WPA artist who worked in Glendale. He died in 1994, mostly unsung, at age 80 — swept into history’s dustbin the same year that the sunset license plate was made.

As Eliot’s poem intones: “I will show you fear in a handful of dust.”

Smith’s assemblage is a layered collaboration. Her hand melds with Yeckley’s, Eliot’s, that of the anonymous designer of the auto tag and Laich’s fastidious lettering.

Today we are accustomed to thinking of art as the product of individual talent, the isolated genius laboring in the studio or dialing up commercial fabrication for a virtuoso idea. Stephen Prina has some fun with that monomaniacal idea in a pointedly titled abstract mural.

“Monochrome Painting” is spelled out in giant letters across a vast field of green, its status as art as dubiously singular as a belief that only one color can go by the name “green.” (It takes a village.) Down on the gallery floor in front of Prina’s wall, Lawrence Weiner’s line of printed text reads “as long as it lasts” — a legend prepared to be trampled into oblivion by anonymous passing feet, fulfilling its own prophecy.

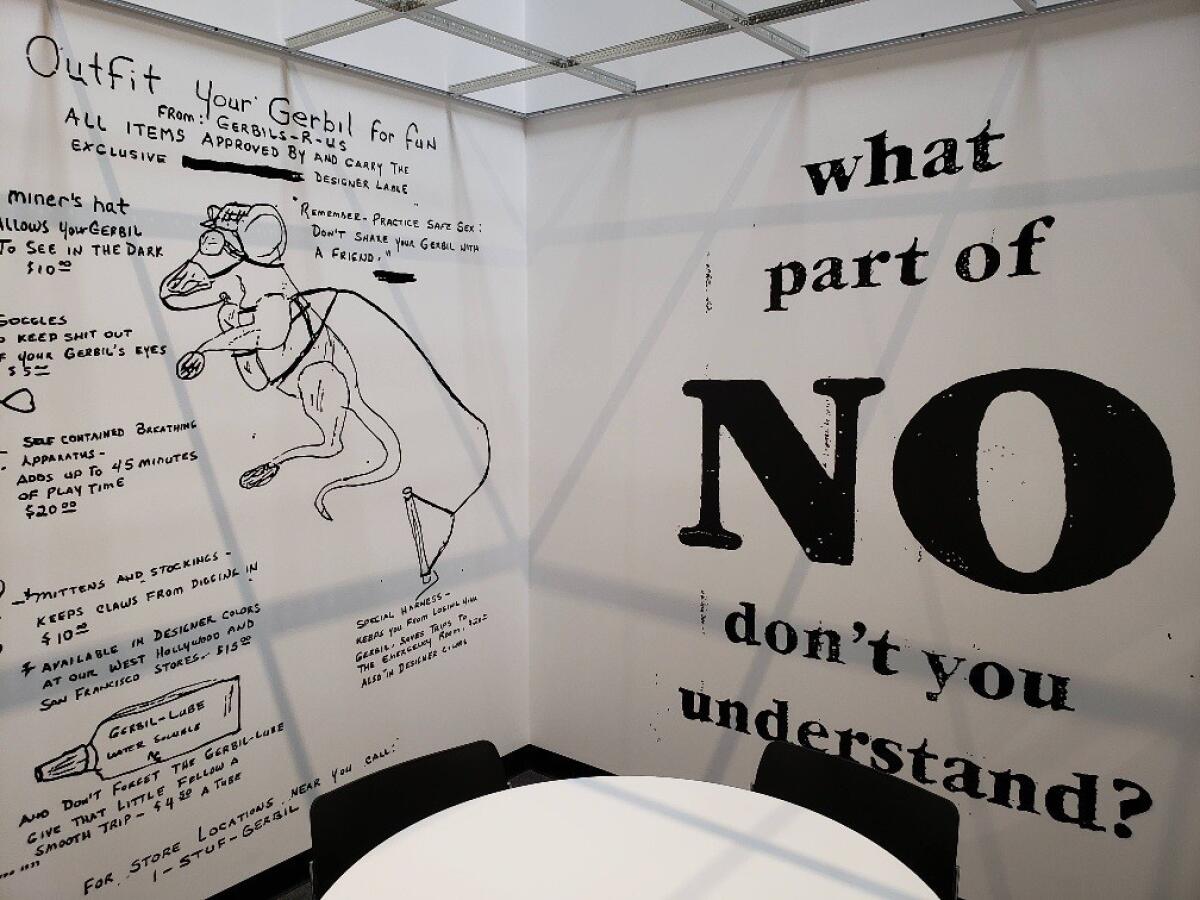

Nowhere is that collective quality more evident than in Kelley’s big, marvelous installation, “Proposal for the Decoration of an Island of Conference Rooms (With Copy Room) for an Advertising Agency Designed by Frank Gehry.” The warren of office chambers hasn’t been shown since its 1992 debut at the landmark exhibition “Helter Skelter: L.A. Art in the 1990s” at the Museum of Contemporary Art.

Laich worked with Kelley to produce numerous wall murals for a prominent advertising agency’s conference rooms. The architectural design — half a dozen white chambers with dark gray carpeting and minimalist furniture — is indistinguishable from a contemporary art gallery, save for the fully outfitted office copy room.

The images papering the walls come from the cheeky Post-it notes and clipped cartoons, often ribald, that enliven and personalize the dreary private cubicles of a conventional workplace. “The flogging will continue until morale improves,” for example. Or “What part of NO don’t you understand?”

Or a guy shown with a large, toothy bite taken out of his posterior and demurring, “Nothing serious… just a little chat with the boss.” The jokes and snarky asides represent a corporate Freudian id, blown up to mural scale and made public.

Kelley grouped the signs in each room by category — toilet humor in one space, sex humor in another, plus women’s work, bureaucratic foibles and anger management in the rest. He bestowed order on the chaos of an instinctual genre notably lacking logic.

Modern painting is generally assumed to be an outward sign of a unique and hidden inner life. Kelley’s installation transforms that assumption into a full-scale public environment.

The apocalyptic obscurity of Abstract Expressionism goes mainstream. Interior messages of power and submission — ready to be reproduced ad infinitum in the copy room — unravel as burlesque. Sad-sack jokes, meant for an ad agency whose business is to generate consumption, bleed unexpected poignancy.

Baldessari, as artist and curator, is the show’s éminence grise. His six-panel “A Painting That Is Its Own Documentation,” begun in 1966 and not finished yet, is a sober list of all the shows in which the painting itself has been displayed over the last 50 years. A functional sign — not unlike a Laich hamburger menu — it’s the show’s artistic patriarch.

It’s disappointing that the exact role Laich played in most of these works isn’t revealed. One happy exception is a short documentary video by Pauline Stella Sanchez that shows Laich using an age-old artist’s technique, similar to tracing, for transferring a drawing to Baldessari’s ever-enlarging suite of canvases. The technique is a descendant of what Michelangelo did on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, a cousin to Marcel Duchamp making art by simply choosing manufactured objects.

Gray painted surfaces with black lettering itemize the 29 shows in which Baldessari’s work has hung — including this one — transforming celebratory events into something like sober tombstones. When space runs out, a new canvas is added. Life — and death — goes on.

########

‘This Brush for Hire: Norm Laich and Many Other Artists’

Where: Institute of Contemporary Art/L.A., 1717 E. 7th St.

When: Through Sept. 2. Closed Mondays and Tuesdays

Info: www.theicala.org

Twitter: @KnightLAT

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.