‘Evan Hansen,’ ‘Great Comet,’ ‘Come From Away’: Tony contenders gather to hash it out

Sure, “Hamilton” had its eyes on us last year. And “La La Land” started a fire this winter. But this Broadway season of new musicals, which crescendoed with a final crash of openings last week, has been a rousing symphony in its own right.

The range of original shows is eye-opening. The postwar swing of “Bandstand.” The coming-of-age timeliness of “Dear Evan Hansen.” The Tolstoyan immersiveness of “Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812.” The idea-stuffed melancholy of “Groundhog Day.” The throwback theatricality of “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.” The feel-good foot-stomping of “Come From Away.”

These half-dozen shows, all eligible for the top Tony Award of best musical, are among the many new productions nominators will consider for the category before announcing their choices on Tuesday. So The Times gathered key creatives in New York and dissected the season. (All made it but those for “Groundhog,” whose principals live or are working outside the city.)

This upstart class of ’17, a number of whom have never worked on Broadway before, convened last week at legendary theater hangout Joe Allen to talk about the changing climate for musicals, the challenges faced by their shows and a Broadway forecast both bright and ominous.

Who’s who in the cast

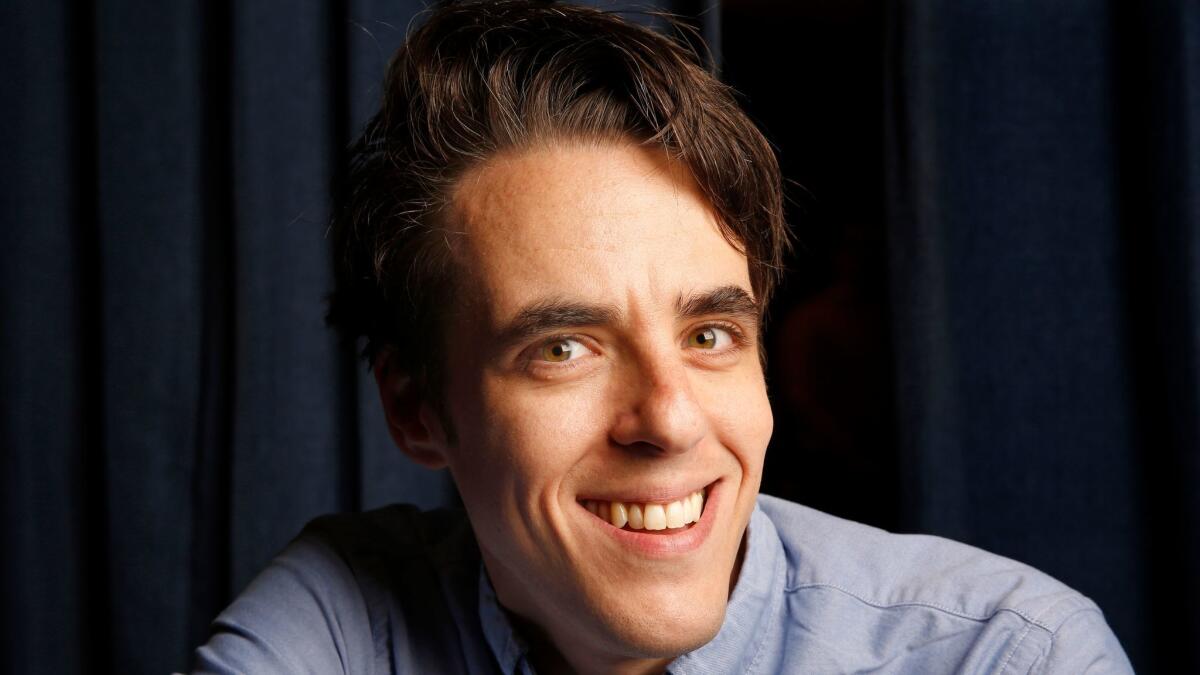

Steven Levenson, book writer of “Dear Evan Hansen.” An acclaimed Off-Broadway playwright, his slick yet intimate musical about a shy high schooler who becomes an accidental viral Internet star has generated big buzz since opening in December. It’s Broadway’s first post-“Hamilton” teen smash.

Andy Blankenbuehler, director and choreographer of “Bandstand.” Blankenbuehler was one of the four creative principals of “Hamilton,” and he won a Tony as its choreographer. The postwar swing musical “Bandstand” — which, with subplots about post traumatic stress disorder, contains notes of the downbeat in a genre of the upbeat — is his directorial debut.

Rachel Chavkin, director of “Natasha, Pierre & the Great Comet of 1812.” Abetted by Josh Groban’s performance and Chavkin’s and composer Dave Malloy’s experimental roots, “Comet” is one of the most unconventional Broadway hits in years — an immersive, style-mashing piece based on “War and Peace.”

Irene Sankoff, composer, lyricist and book writer of “Come From Away.” Toronto-based Sankoff and her partner David Hein are Broadway unknowns. But their musical about a small Newfoundland town where a dozen planes were diverted on 9/11 has become a critical and crowd favorite, with heartfelt characters and a fiddle-heavy score.

Jack O’Brien, director of the

We keep hearing that mounting an original musical is harder than ever. And yet there are so many strong ones this season. So is it easier than people say? Or are you guys just that persistent?

Steven Levenson (“Evan Hansen”): The most exciting thing about original pieces is also the most scary: There's no book to open, no movie to watch. You have all the freedom in the world; the characters can do anything you want. And that's terrifying. And that’s before the commercial [risk]. I remember when we first presented our show to a producer. A musical about 16-year -olds — and one of them kills themselves in the first 15 minutes! It sounded insane.

Andy Blankenbuehler (“Bandstand”): I think you have to be especially passionate about the subject matter with an original musical because you’re dealing with so many abstractions early on that if you also have to be worried about the life of the piece you’ll be doomed.

Irene Sankoff (“Come From Away”): See, we had this freedom because we were starting up in Canada. We never expected it to go to Broadway. We wrote it thinking we’d be in high schools and colleges and they’d have to do it because it’s about Canada. It really let us stay true to the [real-life] characters and events.

Rachel Chavkin (“Great Comet”): It’s interesting that you [gestures to Levenson] had a commercial producer from so early. “Comet’s” history is much more aligned with what you’re saying [motion to Sankoff]. We had no dream of the commercial. We had no idea where it was going. We didn’t have the dream of going to Broadway. We never would have written what we did if we did. I had never even assisted on Broadway ...

Jack O’Brien [cuts in]: I have to say, I’m in another country here. There couldn’t be anything more commercial, more encumbered, than my project. We had no freedom. It was nothing but expectation.

Way to harsh the vibe here, Jack. [Laughter]

O’Brien: The [studio-driven musical] is just a very different world. It’s a stable of people with properties that are trying to figure out what to do with them. Many of the ideas are very possible. And some of them are idiotic. I listen to what everyone here is saying about all the ideas they could come up with from scratch and think: ‘It must be lovely.’ It’s like I’m watching a zoo.

Of course even without corporate oversight it’s not as simple as tossing out great ideas. You have a fidelity to the audience, to the form. Andy, for instance, you’re working within a very hidebound heritage. Did that restrict you?

Blankenbuehler: It’s interesting. With “Hamilton” it was totally new, so in a way we could go wherever we wanted. With “Bandstand” we had this umbrella idea that it was a traditional American musical, so then how do we fit everything into that. It was a different equation.

Sankoff: And you do have to think of other constraints. I remember early on we would want to tell all these stories, tell of so many of the people we met. The first draft of the script was over 100 pages. Being original doesn’t mean you don’t have to make these choices.

You also have the question of why to make it with songs in the first place. If you’re working on a piece as dramatically rich as your show, or as ‘Hansen,’ do you ask, ‘Why is this even a musical?

Levenson: We did think of the show, when we were first building it, as a play. Then it was: How do we get our character was in such dire straits that what he needs to do is sing about it — his life is so out of control, his situation is so desperate, that words won’t suffice. Or he finds it so difficult to communicate with speech that he has to sing.

Chavkin: With ‘Comet’ we didn’t have to deal with the problem of why are people singing because it’s all musicalized; it’s designed as an opera. What we needed to figure out was how to tell Tolstoy’s story with Dave Malloy’s score, which sometimes sounded like Rodgers & Hammerstein, and sometimes sounded like indie rock, and sometimes sounded like headache techno — how do we take all that and build that into the show.

Many of your shows are reinventing the form in some way. How much are you consciously thinking, “Let’s do something that’s never been done before” when you’re writing or workshopping your piece?

O’Brien: I don’t think of it that way when I’m doing it. I just try to respond viscerally. But looking back, some of it is really outrageous. We do tear a girl [Veruca Salt] apart. We do have the squirrels [giant creatures that impose such violence]. I think that’s created confusion with the critics; they say it’s a problematic blend of styles. But it felt organic to us.

Blankenbuehler: I’m very conscious of something not feeling like my parents’ musical. So even though “Bandstand” is swing, swing is not really different from hip-hop. People didn’t know how to articulate what they were going through [after World War II] and there was a lot unrest. So they went to clubs and they played loud music and they sweated. The trick for us was making swing seem cool like hip-hop.

Is that where “Hamilton” helped? You can make the 1700s trendy and so the 1940s isn’t such a stretch?

Blankenbuehler: I don’t think this show would be opening on Broadway without “Hamilton.” I brought ideas to the writing team like, “This doesn’t need a door; she can go into the room without one” because of “Hamilton.” We can take chances and do things because audiences follow in a way they didn’t before “Hamilton.”

Chavkin: But it also drives me a little crazy that people say all these musicals are happening because of “Hamilton.” We started with “Comet” in 2011. I can’t say there’s anything to that except “Hamilton” was so profoundly dominant that some musicals that might have opened last year opened this year, so you get a [backlog] this year.

Levenson: But it did awaken an appetite for the audience, no? It put musicals back into the broader culture.

Chavkin: Yes, it reinforces that it’s popular music. Historically musicals were always standards. And then this weird moment happened when we time-jumped and suddenly you knew immediately you were listening to a “Broadway soundtrack.” It’s very odd.

The idea that Broadway musicals as a genre instead of just a platform ...

Chavkin: It became a type of sound. And that’s changing. I loved walking into “Come From Away,” Irene. You feel the pounding on the floor with a whole different kind of music. And “Hamilton” fed that appetite.

Sankoff: It’s funny, there was this contest up in Canada about what’s the worst idea for a musical. And I kept thinking, “There’s no bad idea for a musical.” You could only write a bad song.

Blankenbuehler: The only downside of that that I’d pose is that the emotions have to heighten enough so that audiences can believe people are singing them. And some things get musicalized that are pedestrian. Sometimes an independent film should stay an independent film.

The question of what should be a musical is interesting. So is, ‘How should it be a musical?’ Which new genres do you think composers might try? Or are there other ways of doing a musical you’re starting to see or are curious about exploring?

Chavkin: I’m seeing a huge proliferation of people downtown and in some uptown channels working indie rock. I’m also seeing narratives where characters aren’t necessarily singing the songs but the music forms the backdrop of the story. That’s a musical form that so far has very rarely been represented on Broadway.

Blankenbuehler: Musicals I think can be in a musical world. It doesn’t have to be about singing. The film “(500) Days of Summer,’ with that Regina Spektor song and the split-screen. Or “Run Lola Run.” I watched those and think: Those are musicals! Even though no one is singing. I think we can see more of those on stage.

I thought “Significant Other,’ which is about a young man looking for love while all his friends are getting married, even though it was a play, almost resonated in your mind as a musical: Songs play a role at key moments, his inner thoughts almost seemed melodious.

Blankenbuehler: Exactly. I don’t think musicals need to just be about people singing.

Levenson: Sometimes, though, what people feel is new or want to be new doesn’t have to be — it can just be good. Well-made or well-crafted. I don’t think every musical has to have contemporary music or a contemporary feel.

O’Brien: May I remind us all that “Cats” came from Andrew [Lloyd Webber] doing concept albums and he was stringing together songs from these [T.S. Eliot] poems. And we’ve evolved past that. Culture acts on us as well. We’ll probably never see “Pajama Game” done the same way again. We’re all hugely saturated by film, for example. Now you can start a film and not justify anything and the audience has to make sense of it. So the same is happening in musicals. I just think every ingestion we take in informs us.

On the subject of film: The studios are staffing up to make a run at Broadway. A lot of them basically want to be Disney. This is on top of the revivals Broadway already does. As creators, are you concerned? Is there any way you can adjust to this?

Levenson: [Sighs.] It feels that theater has worked in part because there aren’t that many gatekeepers. There’s a producer but no president and vice president or chain of command. It’s really an old-fashioned industry: And I think in Hollywood that chain of command is what dilutes and, frankly, runs things. So it will be interesting to see what happens when that structure tries to impose itself.

O‘Brien: Well, there will be a lot of headwinds in the next few years, so strap yourself in.

So where does that take original creators like you?

O’Brien: It takes you to your own integrity. Making a film for a studio and a musical for a commercial entity is not the same thing. A lot of people justify their salaries in Hollywood by saying, can you change that blue shirt to white, and it’s, “Excuse me, who the … are you and what you do?” And we don’t work that way. We know a bad idea when it hits us. So you either knuckle under or you don’t.

But even if you don’t knuckle, the very idea of so many studios controlling Broadway makes one wonder what a musical here will look like. All of the original shows people have been reveling in this season will have much longer odds of making it if so many theaters are basically booking each studio’s version of “The Lion King.”

O’Brien: Well, they still need us. Theater is an empirical science. It works or it doesn’t. It either breathes or it doesn’t. We’ll know from the shows.

Studio invasions on one hand, a lot of shows finding their “post-Hamilton” niche on the other. Would you say you’re pessimistic or optimistic about where the Broadway musical is headed?

Sankoff: I am optimistic — because of all the young people. That’s the biggest thing. I never would have guessed our show would be popular with young people. There’s no one under 40 in it. But I asked an 18-year-old and they said they like it because it moves quickly. “It’s a pace I’m used to.”

Blankenbuehler: I asked my son, who’s 10, to explain a difficult impressionistic moment in “Bandstand,” and he word for word answered it the way I would have. Young audiences are fast and imaginative and hungry.

And they’re also increasingly raised on musical TV shows and movies: “La La Land,” which, Steven, your colleagues Benj Pasek and Justin Paul worked on, or “Glee,” or “My Crazy Ex-Girlfriend.”

Blankenbuehler: I see that with dance too. “So You Think You Can Dance” or the “Step Up” movies. Whatever your point of view is on those things, kids are familiar with the quickstep or the tango or crumping. Their minds are opening to receiving stories in a different language.

It seems almost like the audience gives you reason for optimism but the industry … less so.

Levenson: The audience, especially a younger audience, is hungry for original stories. But I’m optimistic in general too. When I talk to people that don’t do musicals, like my family, the refrain is, “It’s all revivals and movie adaptations.” But look at this table. Look at the row of shows just on our block, one after the other: “Bandstand” and us and “Natasha” and “Come From Away.” There are all these brand new things that are being given a real shot. The future is bright. At least for now.

Twitter: @ZeitchikLAT

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE …

Bette Midler and 'Hello, Dolly!': Our review

Ibsen's radical 1879 play about women's equality gets a 2017 sequel: 'A Doll's House, Part 2'

Center Theatre Group at 50: Angela Lansbury, Chris Pine, Rajiv Joseph and others’ favorite memories

Center Theatre Group at 50: An artistic director plots the second act (Hint: Think Hollywood)

Why Hillary Clinton's next big stage should be at the Tony Awards

Robert Schenkkan's 'Building the Wall,' set in Trump's America

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.