Films once were an escape from work. Now, they celebrate it. What gives?

There was a time when Americans went to the movies to escape the workplace. These days, in keeping with the way our offices have taken over our lives, filmmakers have turned the big screen into one long career day.

Audiences have been invited to experience first-hand the everyday grind of being a journalist (“Spotlight”), an astronaut (“The Martian”), a screenwriter (“Trumbo”), a fur trapper (“The Revenant”) and even an inventor of kitchen mops (“Joy”).

See more of Entertainment’s top stories on Facebook >>

Ever wonder what it was like to be a retail clerk in a fancy old New York department store? “Carol” and “Brooklyn” will happily fill you in on the conversational etiquette of ringing up a purchase.

Moviegoers anxious about what urgent email the boss might be firing off while they’re sitting in the dark for two unforgivably leisurely hours probably won’t be comforted by the sight of Christian Bale’s hedge-fund manager character in “The Big Short” sifting through complaints in his inbox from angry clients. But at least they’ll know they’re not the only ones bouncing from screen to screen in the informational pingpong of the 24-7 workday.

Taken collectively, the somber message of these movies — most of them contenders for best film or acting honors in this year’s Oscar race — is that we have become our jobs. “I think, therefore I am” has been updated to “I work, therefore I exist.”

Not only has private life been squeezed out, but personal happiness, when it is captured, is also celebrated as a boon for productivity.

Saoirse Ronan at work in a scene from “Brooklyn.”

When Saoirse Ronan’s Irish immigrant character in “Brooklyn” falls in love with a handsome Italian American plumber, you know it’s the real deal because even her supervisor is impressed with her newfound confidence in handling customers. In “Carol,” Rooney Mara’s character comes into her own not so much by embracing her sexuality as by switching professions from daydreaming retail drone to driven photojournalist.

Jennifer Lawrence in “Joy.”

Jobs aren’t simply jobs. They’re manifestations of well-being. As the title character of David O. Russell’s “Joy,” Jennifer Lawrence doesn’t forcefully question the fuzzy boundaries of her relationships or the way she’s being exploited by her family. Instead, this former high school valedictorian bemoans her lack of achievement. If she’s miserable, it’s because she hasn’t realized her potential in a career commensurate with her high IQ.

This isn’t a commentary on the quality of the films competing right now for awards bric-a-brac. Movies, a sociological mirror, simply reflect the harried way we live now.

Comic actor Steve Carell plays it more or less straight as money manager Mark Baum in “The Big Short.” But he has the audience raucously laughing in recognition when he makes his boisterous entrance, pounding the city pavement like a storm trooper and treating his cellphone like a physical appendage. His body language provides its own screaming supertitles: “Get out of my way, you nobodies! Can’t you see I’m working!”

Movies about lawyers have long been a Hollywood staple. But “Bridge of Spies” tracks the painstaking negotiations of a New York attorney (played by Tom Hanks) as he wanders through the labyrinth of Cold War Berlin with a bad head cold trying to exchange a Russian spy for two imprisoned Americans. Steven Spielberg and his screenwriters find drama in the bureaucratic intrigue.

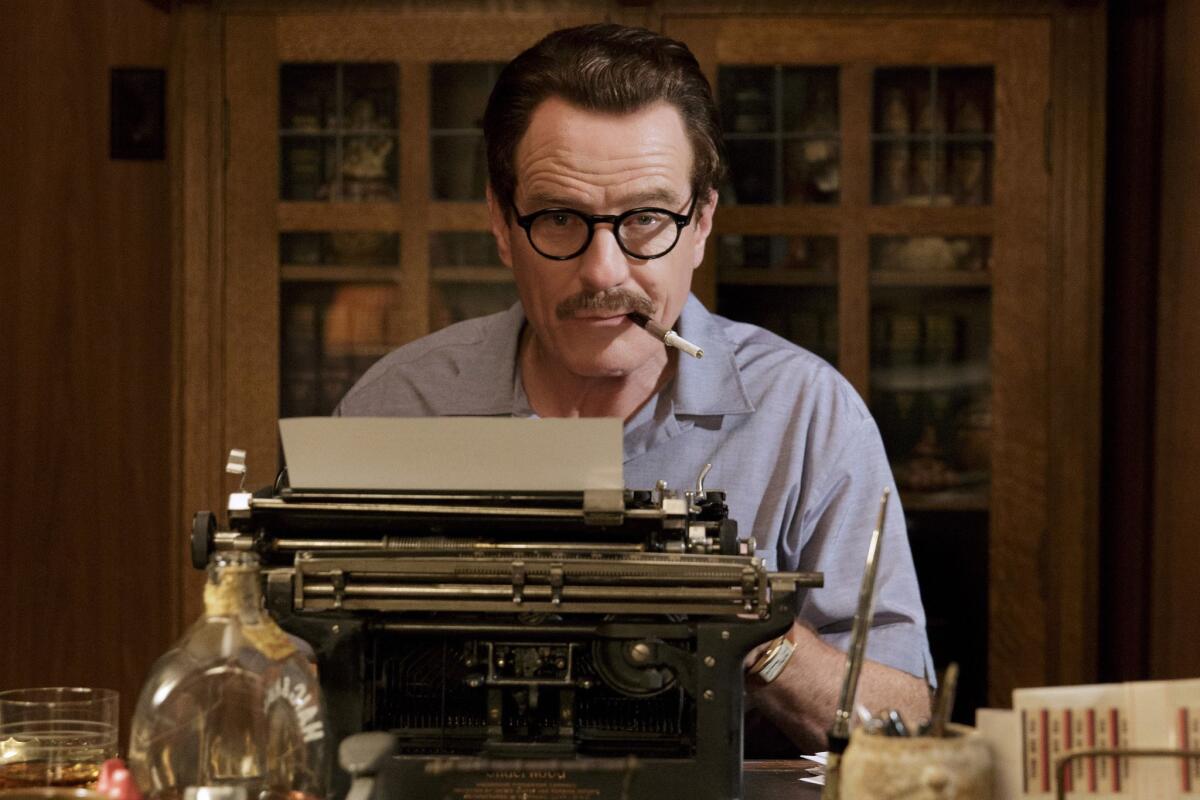

Bryan Cranston as Dalton Trumbo in Jay Roach’s “Trumbo.”

Less successful is the way “Trumbo” tries to turn the act of screenwriting into a spectator sport. The story of Dalton Trumbo, one of the Hollywood Ten blacklisted for suspected political affiliations, is historically fascinating, but even the great Bryan Cranston has trouble making typing at home and shushing noisy kids dramatically thrilling.

As an ink-stained wretch, I couldn’t help being enthralled by “Spotlight,” Tom McCarthy’s stirring re-creation of the Boston Globe investigation of the Catholic Church’s sex abuse scandal, and “Truth,” James Vanderbilt’s inside-journalism exposé on the controversial 2004 “60 Minutes II” report about President George W. Bush’s military record. These were superbly acted films, and “Spotlight” would probably get my vote for best picture. But it did surprise me that some of the more banal aspects of news reporting received so much attention.

If “Truth” were storyboarded, there would be panel after panel of meetings and anxious waiting around for important phone calls. Sure, “All the President’s Men” tracked Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein as they cracked the Watergate story, but “Spotlight” doesn’t merely depict the flash points in the Boston Globe investigation — it fills us in on the archival drudgery and the bureaucratic challenges of copying official documents.

Kitchen-sink realism has apparently morphed into mail-room naturalism, where the aroma of a colleague’s microwaved lunch practically wafts through the screen. Whereas in days gone by a film got its authenticity from a dumpy Brooklyn apartment and a bickering ethnic family, today a movie earns its grit through corporate tedium and an unappeasable boss.

The movies once provided a refuge from the pressures of earning a living. But now, even a film like the “The Danish Girl,” the story of transgender pioneer Lili Elbe, is dominated by occupational concerns — in this case, the business of art. And not just the posing and the painting but the cocktail party schmoozing, the jockeying with dealers and even the carting of work around town.

The idea, often attributed to Freud, that love and work are the keys to human happiness is hardly new. A drama concentrating exclusively on romance, without the least concern for how a character keeps a roof over her head, would seem incomplete in an age in which mortgages (and the complex financing system built around them) have become prime subjects of documentaries and features.

But there’s something a little disturbing about the giddy subordination of private to professional life. This isn’t just the price one pays for having a relatively interesting job. Workaholics have become our modern-day heroes.

This sentiment reached a near comic crescendo in Ridley Scott’s “The Martian” when the members of the Hermes crew unanimously agree to rescue the astronaut they left stranded on Mars even though it will add 533 days of unplanned space travel to their mission with no guarantee of success or even safe return. Tough luck for their spouses, kids and pets waiting back home. These gung-ho space cowboys might have had a more agonizing time deciding on their evening meal packets.

Layabouts beware: Moral character is now revealed in our refusal to stop working. Of course, Mark Ruffalo’s journalist in “Spotlight” deserves a Pulitzer: He’s so dedicated he can’t bother to furnish an apartment or stock his fridge. The authenticating mark of the financial genius Bale portrays in “The Big Short” is his inability to socially interact.

These characters, based on real-life figures, aren’t presented as psychological ideals. But what distinguishes them from their colleagues is what alienates them from nearly everyone else: their ability to subsume themselves entirely in their work.

Neither “Spotlight” nor “The Big Short” endorses such a single-minded focus. Ruffalo tinges his portrayal with a haunting loneliness. And in “The Big Short,” the characters played by Carell and Bale are left deeply troubled by their success in out-maneuvering the rigged financial system. They’re vastly richer yet morally spent after the crash hits. But the sense that life is larger than our professional identities flickers only faintly, the shadow of some distant, hard-to-discern object on the periphery of these cinematic stories.

It was a better-than-average year for intelligent American movies, and it’s good to see screenwriters and directors grappling with the value of our labor. But at a time when wages have stagnated despite productivity gains, when wealth is being amassed only at the very top and the rest of us are having to scratch and claw merely to hang on, filmmakers might want to cast a more critical eye on the way we have come to define ourselves through our work.

The movies don’t have to simply mirror our compulsive busyness. They can provide an opportunity for us to get off the relentless merry-go-round and take in the bigger picture. They can also enhance our appreciation for what the Italians call “dolce far niente” — that sweet idleness overworked Americans might start finding less objectionable as the dream for which they have been slaving away slips only further out of reach.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.