In defense of anger: A critic’s appeal to playwrights to let their tempers fly

At a time when voters are by all accounts mad as hell and not willing to take it anymore, the conditions seem ripe for an American version of the Angry Young Men movement that transformed the postwar British theater.

The charge led by John Osborne in 1956 with “Look Back in Anger” successfully brought the furious proletariat into the spotlight. In an instant, drawing rooms of chitchatting swells were bulldozed to make room for under-heated flats, where working class hotheads were finally allowed to get a few things off their chests.

Of course a 21st century U.S. version of this theatrical phenomenon wouldn’t be just for the Osborne-inspired bros. Women, still earning less on average than their male counterparts, have perhaps even more reason to look back in anger.

But playwrights from the allegedly over-parented millennial generation don’t seem particularly comfortable venting their spleens. Playing nice is ingrained. Like their Gen X predecessors, they tend to rely more on irony than ire.

Could bad tempers be an outdated luxury of baby boomers? Maniacs, as Jesus said of the poor, will always be with us, though I’m not talking about rampaging psychotics. I’m on the lookout for those willing to take a forceful stand against oppression and injustice, those brave enough to unapologetically demand a clarifying corrective to the way business is being done.

Inciting fury over a ludicrous status quo has been part of the dramatic tradition since the ancient Greeks.

Overgeneralizing about millennials has become a journalistic pastime but growing up with technology has conditioned this group to translate its anger into fiery emoticons and social media snark. Political passions swing freely in the classroom, but these laid-back activists would rather “occupy” a park than storm the proverbial ramparts.

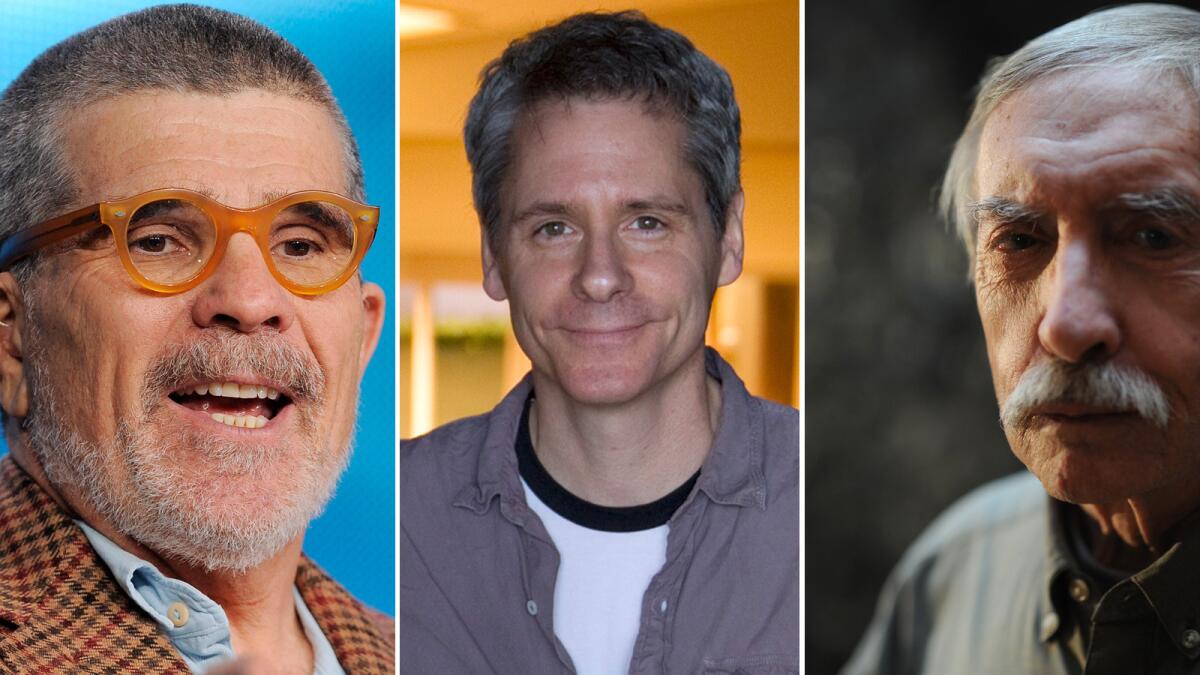

The generational distinction is reflected culturally as well as politically. Stylists of truculent comedy, Edward Albee, David Mamet and Bruce Norris, three dramatists who have long been eligible for AARP membership, are renowned for giving indignation free theatrical rein. Never at a loss for a lethal quip, Albee has long dramatized the highball-clinking sadism of the upper crust. Mamet’s cussing crew have shown what dog-eat-dog capitalism can make men do. Norris has been brewing a comedy so toxic with hypocrisy and resentment that the laughter practically scalds our throats.

Younger playwrights such as Annie Baker, Tarell Alvin McCraney and Samuel D. Hunter, to name three of our most talented dramatists under 40, seem like good Samaritans by comparison. Their Chekhovian empathy dulls the edge of villainy in their plays. Post-structuralism, still the philosophical mother’s milk of literary studies, has taught them that the system is to blame, and so they opt to contextualize rather than to indict. Tout comprendre c’est tout pardoner — to understand all is to forgive all — could sum up their collective worldview.

But given the melodramatic scale of our problems — an environment turning apocalyptic, an economy dancing attendance on the super rich and racial injustice still getting away with murder — maybe the bad guys need to be smoked out. If nothing else, the theater, the most democratic-minded of the arts, could be doing a better job of intelligently channeling the mounting frustration of the public.

In life, making a tumultuous scene is a sign of poor manners, but on the stage it’s more or less a requirement. The great playwrights provoke us not for provocation’s sake, but to wake us up. Inciting fury over a ludicrous status quo has been part of the dramatic tradition since the ancient Greeks.

If society is in danger, it is not because of man’s aggressiveness but because of the repression of personal aggressiveness in individuals.

— D.W. Winnicott

Aristotle was the first to formally recognize the salutary function of stoking the more clamorous emotions through drama. Catharsis, in his view, wasn’t just healthy for the individual — it was good for the state. The term is often interpreted as a purgation of pity and terror, but an alternative understanding suggests a clarification of those feelings dramatists are bringing to a boil. The goal isn’t just equilibrium but enlightenment.

The influential 20th century British psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott opens one of his papers with a modern defense of anger: “If society is in danger, it is not because of man’s aggressiveness but because of the repression of personal aggressiveness in individuals.”

I copied this provocative remark into a commonplace book of mine crowded with wisdom from Shakespeare, Chekhov and Proust and have long pondered its implications in the field of drama. My understanding of Winnicott’s thinking about the role of aggression in child development is admittedly incomplete, but his belief that the expression of aggressive impulses (anger included) is essential for the achievement of an autonomous identity and that inhibition of this energy can have a warping effect is readily applicable to an art form that thrives on conflict.

Change, growth, the movement of consciousness toward maturity — the short story tends to depict these processes with serene melancholy, but the stage is a more head-butting place. For a theatrical character to transform, present circumstances must be challenged. The bigger the obstacle in a protagonist’s path, the more explosive the drama.

Anger bespeaks conviction (you don’t defend or oppose what you don’t care about), but its bad reputation (for being irrational, for making people lose control) isn’t undeserved. The dramatic repertoire is replete with examples of characters either paralyzed by resentment or transformed into vengeful monsters.

Sophocles’ Philoctetes is so furious at his comrades who deserted him on a desert island that he is willing to pass up his only chance at rescue if it means having to help them in their war against the Trojans. The incontinent rage of Shakespeare’s Timon of Athens may be wholly explicable but it is as much a character flaw as his former prodigal generosity. The marital combatants in August Strindberg’s “The Dance of Death” give “irreconcilable differences” a bad name.

Why should our political theater be tamer than our political reality?

But dramatic plots move inexorably toward confrontation. The building blocks of tragedy may be two characters and a dispute with no easy resolution. This might sound overly simple, but revolutions have sprung from such basic stage tussles.

The greatest example may be Ibsen’s “A Doll’s House,” in which Nora, disillusioned by the cowardice of her conventional husband, slams the door on their marriage in an ending that sent shock waves throughout Europe after the play’s 1879 premiere. The patriarchy, some might argue, has yet to recover.

I’d like to see more playwrights follow Ibsen’s lead and raise hackles. Theatrical decorum is there to be overturned. To avoid offending anyone in the audience is to settle for the most anodyne drama.

The better playwrights are inevitably drawn more to questions than answers, but in turbulent times a God-like neutrality can seem like an abdication of responsibility. To put the matter in Yeatsian terms: Why should the best among us, our writers, lack conviction, while the worst, a tough call but let’s go with our representatives in Congress, be full of passionate intensity?

This year’s Tony winner for best play, Stephen Karam’s “The Humans,” tackled head on the beleaguered state of the middle class, though more with melancholy resignation (“don’tcha think it should cost less to be alive”) than with a furious appeal to fairness. The play is deeply moving in its compassionate depiction of these scrambled lives, but I longed for just one of the characters shafted by the new economy to shout something akin to Willy Loman’s bitter retort to his boss in Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman”: “You can’t eat the orange and throw the peel away — a man is not a piece of fruit.”

No one is arguing for characters to devolve into a ruckus of name-calling and fisticuffs. Most of us have had our fill of vitriolic family drama. (I reached my satiation point after Tracy Letts’ “August: Osage County.”) But why should our political theater be tamer than our political reality?

Wunderkinds Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, a playwright who marries a heightened social awareness with a playful postmodernism, and McCraney, a dramatic poet whose conscience is communicated through music and myth, are extraordinary talents. But in this era of Black Lives Matter, the American theater could use some of the insurgent energy of the late Amiri Baraka, whose play “Dutchman” translated the civil rights struggles of the 1960s into pugnacious theater.

Yet what if the rage just isn’t there to call up? A Freudian would say seek and ye shall find. I would ask writers to consider how the desire for success might be making them more circumspect about voicing unpleasantries. But repression provides its own fund of rich material.

Young Jean Lee’s “Straight White Men” looks at what happens to a group that no longer feels it has a legitimate claim to anger. Conscious of their white male privilege, a father and his three grown sons have trouble articulating their conflicts with one another and the wider world. Instead of hashing out their differences, they act out their feelings in horseplay and various forms of cultural appropriation. When matters are finally brought to head, the outcome, distorted by the neatly pressed straitjackets of their identities, is brutal.

Comedy has traditionally been a safe vehicle for angry young men and women to air their gripes. Laughter makes it easier to listen to a rant. Yet whether couched in humor or spoken in deadly earnest, those subjects that incense us are artistically invaluable. Not only do they reveal ourselves to ourselves but they expose the cracks in a broken world.

Follow me @charlesmcnulty

MORE:

On TV, rage has become the new romance

Anger is an energy for a new wave of women in pop culture

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.