Review: ‘Mark Bradford: New Works’ at Hauser & Wirth

Long before homelessness became the issue it is today, the critic Clement Greenberg coined the term “homeless representation” to put down paintings that were not abstract enough.

The champion of Abstract Expressionism (and Post-painterly Abstraction) looked down on art that made viewers feel as if they were in the presence of a world that did not exist — except in the mind’s eye. To Greenberg (1909-94), that was the stuff of science fiction; it had no place in painting.

At Hauser & Wirth in downtown Los Angeles, “Mark Bradford: New Works” turns Greenberg’s idea of homeless representation inside out. Rather than being a pitfall to painting, the imaginative leaps that homeless representation triggers give Bradford’s art its kick and resonance.

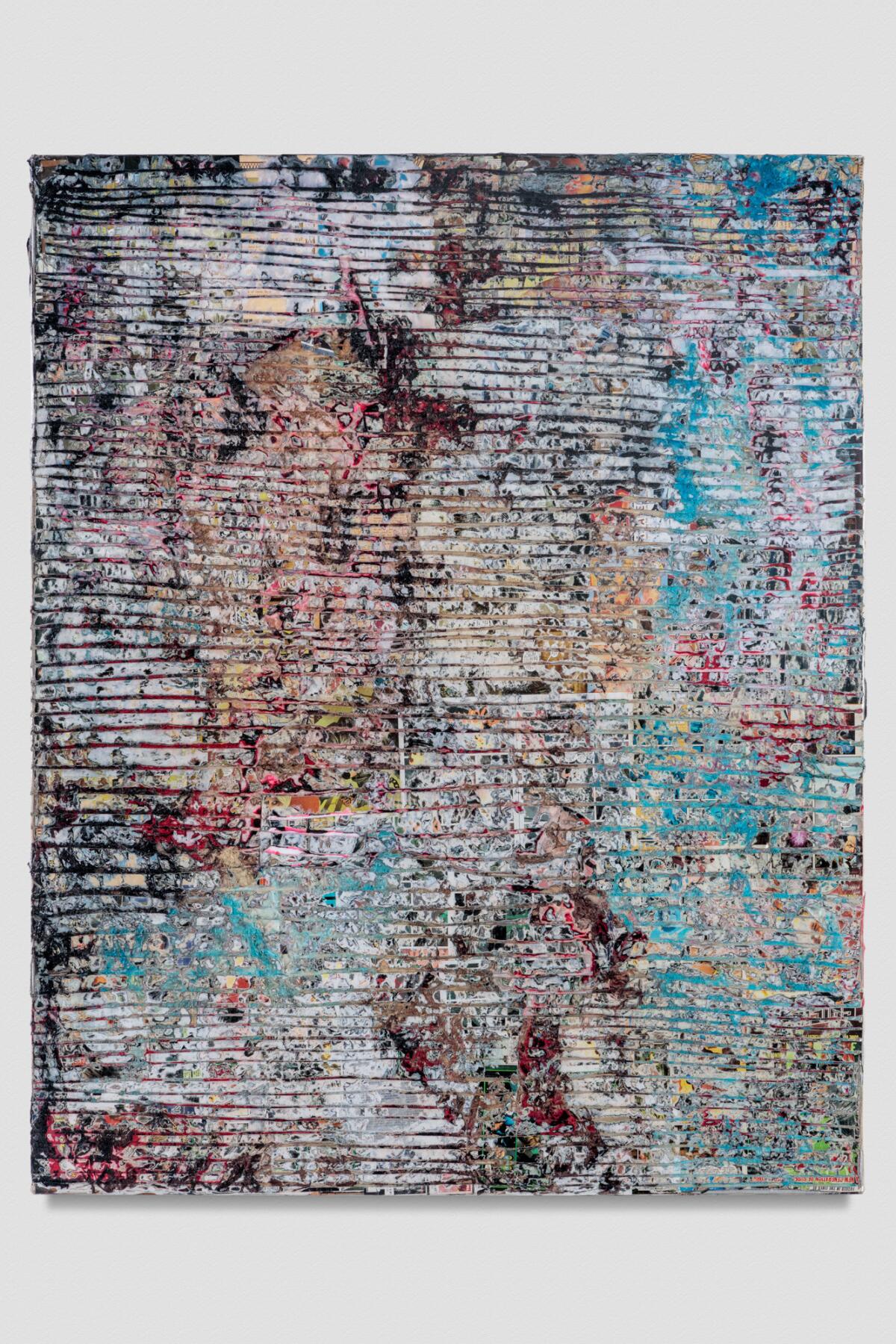

Lines run every which way. Some form networks that resemble a drone view of streets and buildings — before, during and after missile attacks. Other patterns recall the visual glitches of old-fashioned TVs, their antennas intermittently picking up signals and their screens appearing to be possessed by shape-shifting demons.

Think of his work as homeless abstraction, a kind of painting all about displacement and the seismic shifts society is undergoing.

Violence ripples across the scarred surfaces of Bradford’s 10 canvases, all made in 2018. Each weighty slab has the presence of a battle-damaged wall or a chunk of terrain that has been subjected to the scorched-earth tactics of warring armies.

Brushstrokes are nowhere to be found. Yet colors collide, making sparks fly. Ghostly imagery nearly congeals into recognizable shapes and forms, but before you can put your finger on the identity of anything it disintegrates into a blur.

To make each painting, Bradford glues layer upon layer of printed imagery — from comic books, newspapers, magazines, posters and billboards — on large canvases. He also slathers and dumps big jars of paint atop, forming thick, sedimentary-style layers. Eventually he cuts into his paintings with woodworking tools and razor-sharp blades, sometimes tearing off scab-like sections and at other times slashing vigorously.

The process recalls Jacques Villeglé’s torn poster collages from the 1950s and ’60s as well as Alberto Burri’s burlap, wood and plastic pieces from the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s, which he often burned to a crisp.

But the way Bradford cuts into his works is all his own: a painstaking process of rooting through ugliness to make something beautiful. The lacy delicacy of his incised lines is all the more poignant for the in-the-street scrappiness of the detritus in which it is embedded.

Beauty doesn’t come out of nowhere; it gets clawed out of what Bradford has found in the trash: printed forms of communication. That may be tragic, but it’s also realistic, a matter not for science fiction but for painting.

Hauser & Wirth, 901 E. 3rd St., L.A. Through May 20; closed Mondays. (213) 943-1620, www.hauserwirthlosangeles.com

See all of our latest arts news and reviews at latimes.com/arts.

ALSO

Harry Gamboa Jr. and Luis Garza push back against 'bad hombre' stereotypes

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.