‘Scandal’ actor Joe Morton on Charlottesville, bigotry and reviving the activism of Dick Gregory

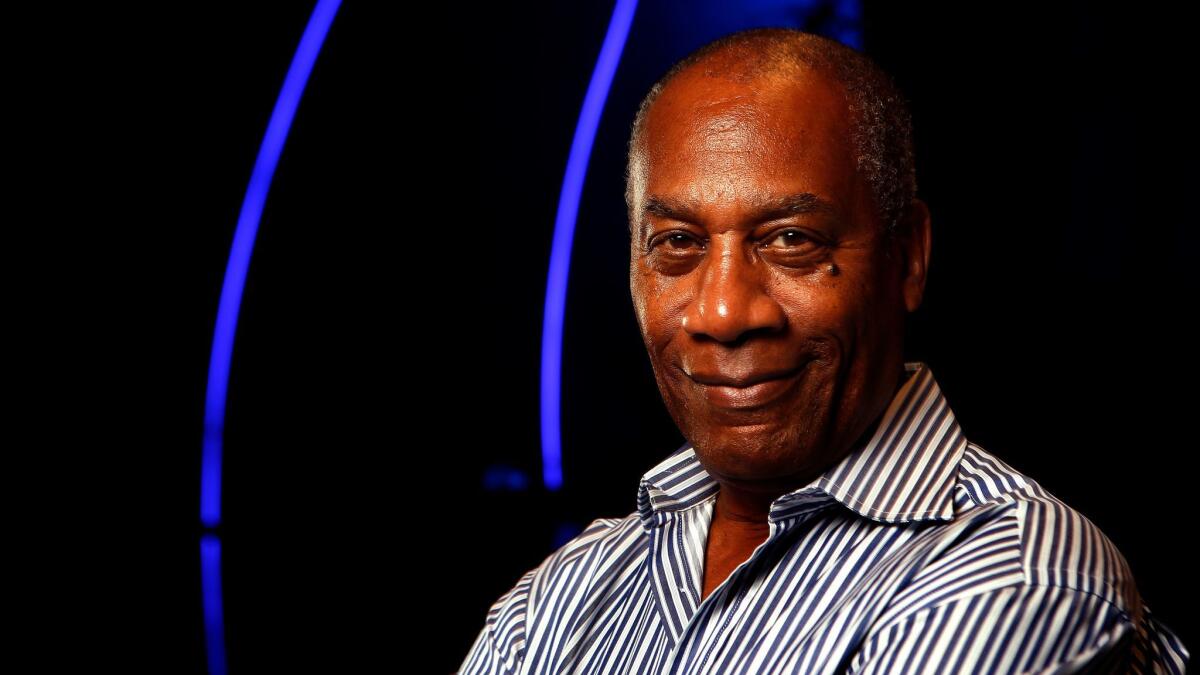

Joe Morton, best known these days as Rowan “Papa” Pope, Olivia Pope’s fiercely protective father on the ABC series “Scandal,” is in the posh Founders Room of the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts in Beverly Hills. It’s where next month he will open “Turn Me Loose,” a play on the late comedian and civil-rights activist Dick Gregory.

Morton originated the role last year when this high-profile production — John Legend is one of its producers — had its off-Broadway premiere. Morton didn’t read the reviews, he says. He didn’t need to.

“At the opening party, one of the producers came in and said, ‘They’re through the roof,’” Morton recalls. “And my girlfriend read all these reviews and kept wanting to tell me what was in them, and it seemed that everybody liked what they saw. And that’s every reason not to read a review, because then you begin believing everything everybody says about it instead of just going to work every day.”

“Going to work” in this case means carrying a 90-minute show based on the long and varied career of Gregory, who died of heart failure at 84 just a few weeks ago. Artistic Director Paul Crewes, who selected “Turn Me Loose” to kick off his second season at the helm of the Wallis, says the theater had planned a double celebration in honor of Gregory’s 85th birthday and the play’s opening.

FULL COVERAGE: Fall 2017 Arts preview »

“I would have been proud to have hosted him here at the Wallis,” Crewes says. “I certainly feel a responsibility to make sure that as many people as possible will be made aware of his life, his achievements, his involvement in the civil-rights movement, his beliefs in social justice, and his comedy that revealed a wisdom and truth.”

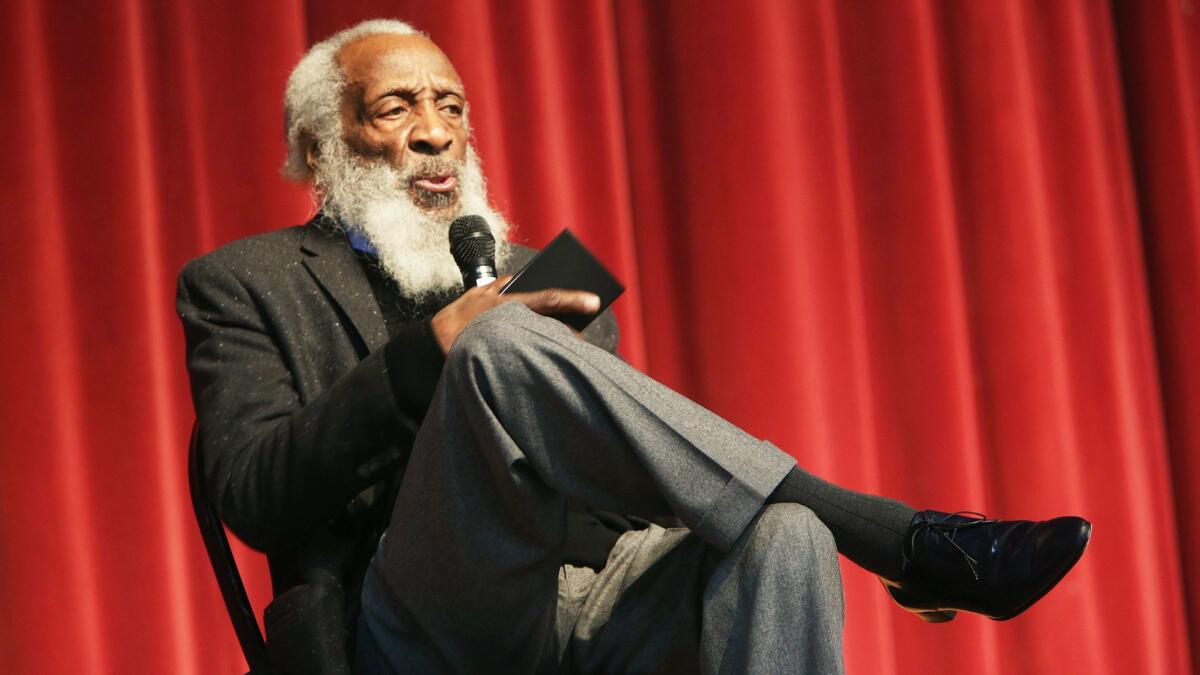

Gregory’s talents, passions and impact on American culture are difficult to sum up. He started in the 1960s as a laid-back stand-up comic, coolly balancing a cigarette and a drink onstage as he told jokes about racism that still — all these years later— cut deep: “Last time I was down South I walked into this restaurant, and this white waitress came up to me and said: 'We don't serve colored people here.' I said: ‘That's all right, I don't eat colored people. Bring me a whole fried chicken.’” The first time he appeared at

He went on to become the first black entertainer whom host Jack Paar invited to sit on the couch of “The Tonight Show” — because he refused to appear otherwise. As his fame grew, Gregory threw himself passionately in the civil-rights movement, becoming close friends with fellow activists Medgar Evers and Martin Luther King Jr. (“Turn me loose” were the dying words of Evers, whose murder by a white supremacist in 1963 had a profound effect on Gregory.)

Gregory then eschewed stand-up gigs for protest marches and rallies, where he was beaten and arrested. In the 1980s he reinvented himself as a nutritionist, marketing a popular weight-loss program based on his 20 years of protest-fasting. He ran for president of the United States and mayor of Chicago. He wrote two autobiographies, one of them using a racial slur as its title. (His explanation: If his mother heard people saying that word, she’d know they were advertising his book.)

In his 80s, wearing a distinctive snowy beard, he still made appearances, delivering his combination of humor, painful truths, nutrition advice and conspiracy theories to a new generation. He died Aug. 19.

In “Turn Me Loose,” Morton plays the laid-back thirtysomething, the fiercer and more fragile octogenarian, as well as various Gregorys in between, all without makeup or costume changes. According to playwright Gretchen Law, who knew Gregory well, “Joe alternates between them so seamlessly, just from his pure acting skills and, I think, his deep feelings about Dick Gregory. He just got what I was trying to say about Dick in the play, which is that he was one of the funniest people who’s ever lived, and also one of the brightest, and one of the most courageous.”

Workshops and rehearsals had to be arranged around Morton’s “Scandal” schedule, but he says he didn’t mind being busy because “Turn Me Loose” was so important to him.

“Dick’s experiences in the play are things that I’ve experienced on my own,” he says, “and the things he says are things that I wanted to say, that I thought needed to be said.”

Morton may not have read the critics’ raves, but he did pay attention to the reactions of Gregory’s 10 grown children, who showed up at the theater “either one by one or two by two” throughout the off-Broadway run. When Morton met them, he recalls, “I would always say it must be weird to walk into a theater and see someone portraying your father. One of the greatest compliments I got, his oldest daughter, Miss, said, ‘Yeah, for a couple seconds, but then I was just looking at my father.” Gregory’s youngest son, Christian, told Morton that when people ask him what his dad was like during his childhood — when Gregory was frequently away from home — he has taken to referring them to the play.

Morton also performed for Gregory, who attended the New York opening last year with his wife, Lillian. At an emotional moment, Lillian told Morton afterward, Gregory reached out to take her hand. She hissed at him, “What are you holding my hand for? That’s Dick Gregory up there!”

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

Several New York critics observed that the relevance of Gregory’s material today — after all his efforts to fight bigotry — is disheartening. “If we’re still talking about the same thing, 40 or 50 years later, then that means we’re not doing anything about it,” Morton says in agreement.

Gregory died the weekend that white supremacists marched in Charlottesville, Va. Morton doesn’t think the events would have come as a shock to the activist, explaining in an email: “I think he would have advised that it is America, despite

This story is part of our Fall 2017 arts preview. See our complete coverage here.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

‘Turn Me Loose’

Where: Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts, 9390 N. Santa Monica Blvd., Beverly Hills

When: Oct. 13-Nov. 12. Performances are 8 p.m. Thursdays and Fridays; 2:30 and 8 p.m. Saturdays; 2:30 p.m. Sundays. No performance on Nov. 9.

Tickets: $60

Info: (310) 746-4000, www.thewallis.org/tml

Support coverage of the arts. Share this article.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.