Column: Ridership climbs, planning efforts lag as Expo Line extension marks first birthday

How do you judge a new light-rail line? How do you decide if it has succeeded or failed? How do you measure the ways it has changed — or failed to change — a neighborhood? A city? A region?

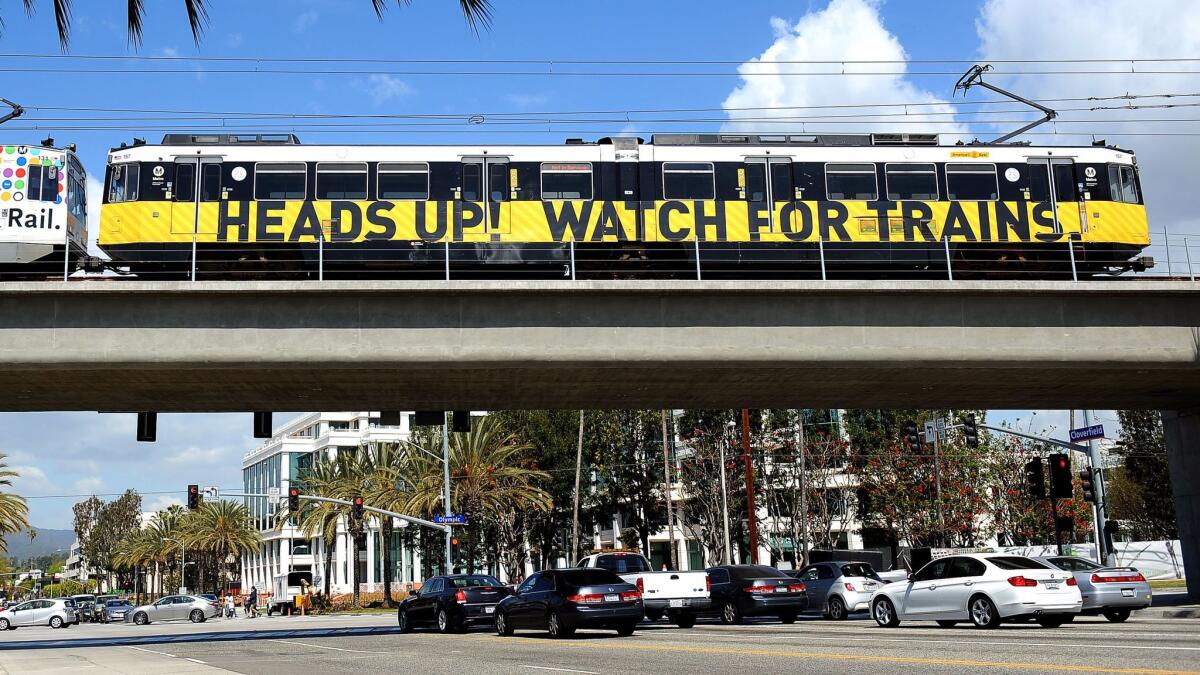

These are questions that Los Angeles County, as it pursues an urban rail expansion as ambitious and expensive as any in American history, is going to be asking itself regularly over the next couple of decades. They’re especially relevant this spring as the newest part of that growing rail network, the Metro Expo Line, marks a double anniversary.

The line’s first phase, linking downtown with Culver City, celebrated its fifth birthday at the end of last month. An extension west to Santa Monica — which took Expo across the 405 Freeway, a major milestone both practically and psychologically — opened a year ago this weekend.

Ridership has outpaced expectations. Passenger numbers have climbed steadily since the second phase opened. So far this year, Expo has averaged more than 1.5 million passengers per month. Only the Blue Line, which opened in 1990, carries more people.

In other ways, the story has been less rosy. Strong Expo numbers have helped mask larger weakness across the Metro system as a whole, where total passenger numbers continue to fall, thanks in large part to cratering bus ridership.

And the quality of service on Expo, in a range of ways, has been disappointing. As my colleague Laura Nelson has reported, a shortage of rail cars led to overcrowding. Along the first leg, in and around downtown, Metro trains too often have to wait at intersections to let cars through. Traveling from one end of the line to the other takes at least 45 minutes and often closer to a full hour.

As an architecture critic, I’m more interested in the broader urban design and planning effects of rail expansion. And here the record is also mixed.

There’s no denying that the Expo Line has transformed our collective mental map of the region in important ways. For Metro passengers, the barrier between the Westside and the rest of the L.A. represented by the 405 — a kind of iron curtain for drivers — has gone away. Expo, by weaving above and below the 10 as it makes its way to Santa Monica, has also begun to make the north-south divide created by that freeway seem less daunting.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

When it comes to making sense of the zoning strategy for the neighborhoods along the line, alas, it’s a matter of picking our poison. Should we focus on the fact that new zoning plans for the Expo corridor in Los Angeles and Santa Monica have yet to be implemented? Or that the plans, as written, are so watered down by worries about density and new development as to be effectively meaningless in attacking our acute housing shortage?

In a city and county with a healthy approach to the relationship between mass transit and housing, the planning strategy would have been in place before the line opened, to take full advantage of the ripple effects of investment and new demand nearby.

Instead, we executed Step 2 before Step 1. And now we’re arguing about whether we need Step 1 at all.

In April, L.A.’s Department of City Planning released a new draft version of the Exposition Corridor Transit Neighborhood Plan, which covers properties within half a mile of the Expo Line from Culver City west to the Santa Monica line.

The plan as it now reads doesn’t go far enough in allowing new density near the Expo Line; it is too timid for a city and region that have systematically underbuilt housing for more than three decades. To the extent that there are some good ideas in it, including modest challenges to rigid parking requirements and urban-design guidelines that pay attention to the needs of pedestrians, the more immediate problem is that it remains a mere proposal. It has been slowed by a familiar combination of paltry planning budgets at City Hall and opposition among many neighborhood groups to zoning changes that would allow denser housing.

The planning department is continuing to solicit input on the plan and will hold a public meeting May 23 to collect yet more opinions. As for when it might become binding, the department’s website says only that “later this year the Plan will be presented to the City Planning Commission for their recommendation and to City Council for final adoption.”

In Santa Monica, a new Downtown Community Plan suggesting that current height limits for new buildings be maintained along the Expo Line and lowered (yes, lowered) elsewhere has drawn fire from affordable housing advocates, among others.

The plan remains, as you have probably guessed, in draft form.

There’s no denying that the Expo Line has transformed our collective mental map of the region in important ways.

One final example of this general sluggishness: On a hot afternoon last month, I was given a tour of a potential new park, stretching 800 feet on both sides of the Expo Line’s Westwood/Rancho Park station, by a group of nearby residents. The site already has a name, the Westwood Greenway, and the advantage of already being empty of buildings and under public ownership.

The greenway will be a place for native plants to flourish and a sort of natural machine for treating storm water. There are also plans to use the space as an outdoor classroom for public schools with campuses along or near the Expo Line.

The greenway’s leading champion, an attorney and Cheviot Hills resident named Jonathan Weiss, has been working to get it open since 2009. He won a partial victory when Expo planners abandoned an earlier effort to turn the space into a parking lot with 170 spaces.

Yet the site remains fenced off. It’s a greenway in name only, just as the Los Angeles and Santa Monica rezoning efforts are plans in name only. Tellingly, it’s located next to the Expo Line bike path, which has a major gap in Cheviot Hills thanks to opposition from nearby residents.

What this collection of stalled efforts suggests is that the questions I posed at the start of this column remain to a large degree unanswerable.

In earlier Los Angeles booms, there was a clear connection between mobility and regional planning. A century ago, residential tracts were laid out, parks planned and apartment blocks built in anticipation of new streetcar lines. In the years after World War II, subdivisions were designed to take full advantage of new freeways.

In this boom, that link has been largely severed. Despite all the talk about how Los Angeles is changing much more quickly than some residents would like, with elected officials across the county selling out to developers and other special interests, the land-use status quo remains the most special interest of all.

Building Type is Christopher Hawthorne’s weekly column on architecture and cities. Look for future installments every Thursday at latimes.com/arts.

Twitter: @HawthorneLAT

MORE BUILDING TYPE:

Design for Obama library and museum off to surprisingly somber start

Harvard’s first online architecture course: Does it make the grade?

For the late L.A. architect Paul R. Williams, bleak timing for an overdue honor

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.